Thesis: Eleanor Garside

Neuroarchitecture seeks to understand what makes an optimal space for someone affected by dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The aim is to create an environment that supports people with cognitive decline as their disease progresses, for as long as they need. Traditional approaches to care are questioned and instead proposed is a future state where dementia patients are no longer trapped inside “a prison without bars.”

Today, families and caregivers have limited options when it comes to quality care for their loved ones with dementia. Nursing homes are outdated, institutional environments that lack freedom, joy, and a broader community for residents. Some facilities try to imitate real life with the integration of general stores, a post office, and other town shops. Yet, those places isolate residents and leave them with less opportunities to engage with the local, intergenerational communities.

Can we leverage our understanding of the brain and its reaction to space to retain independence, create joy, provide purpose, and strengthen community through design?

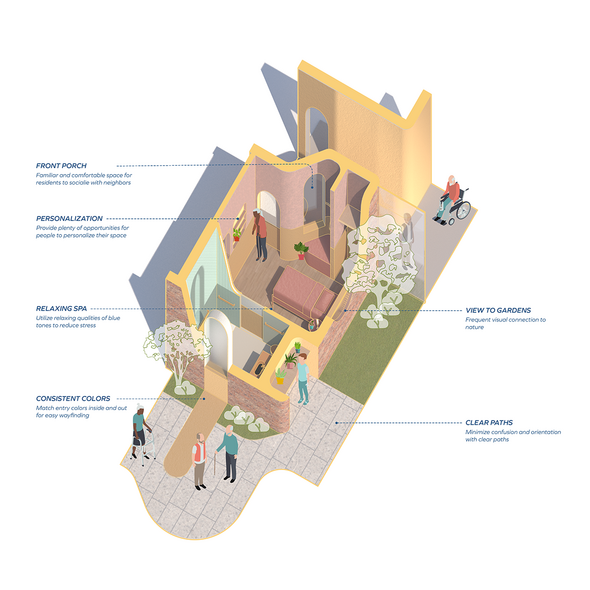

Design strategies exist based on research by neuroscientists and architects which alleviate some of the symptoms of dementia in relation to how one interacts with their environment. These include utilizing circadian lighting to minimize sensory overloads of harsh lighting or limiting contrast in flooring to help with depth perception, all to mitigate the effects of disorientation, confusion, and other symptoms. Wandering is one of the most prominent concerns for people with dementia in fear they will get lost or injured. There is an innate desire for people with dementia to wander and their environment induces triggers to wander constantly. Some strategies currently include establishing safe zones near exits where wanderers end up and organizing touch points within the building people can easily find and make their way back to. These strategies are merely a starting point, piecemeal elements that are not suggested for optimal environments, however not always implemented.

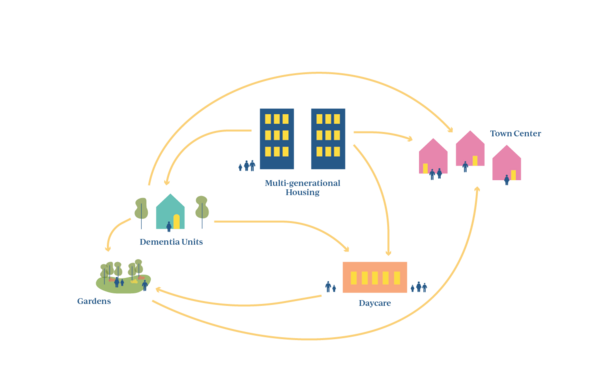

The importance of community is elevated with the integration of market rate, intergenerational housing on the site. Twenty-four 2-bedroom apartments offer housing for local families with or without a loved one in memory care. A daycare provides childcare for the neighborhood and residents with dementia can help with the children, facilitating connections with younger members of the community. Greenhouses and gardens provide space to grow produce which is cultivated to be sold back to the community as well as supplied to the residents. Partnerships with the local community such as the daycare and greenhouse provide a symbiotic relationship and holistic support for those with dementia. These relationships also have an economic benefit to the residents with dementia, who typically pay an average of $6,500 per month for memory care in Boston, MA. To combat this debilitating price tag, the residents in the apartments pay a community fee for access to the amenities such as fresh produce from the greenhouse and gardens, a fitness center, multipurpose rooms, outdoor spaces, and underground parking. Those fees, along with the profit from the greenhouse and daycare, circulate back into the community and the cost for people with dementia is reduced, lifting the burden off of their families and caregivers.

A day in the life for a resident at this new community gives people the freedom to explore, to have daily purpose and joy, create meaningful connections, and overall an elevated quality of life.