November 22, 2017

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

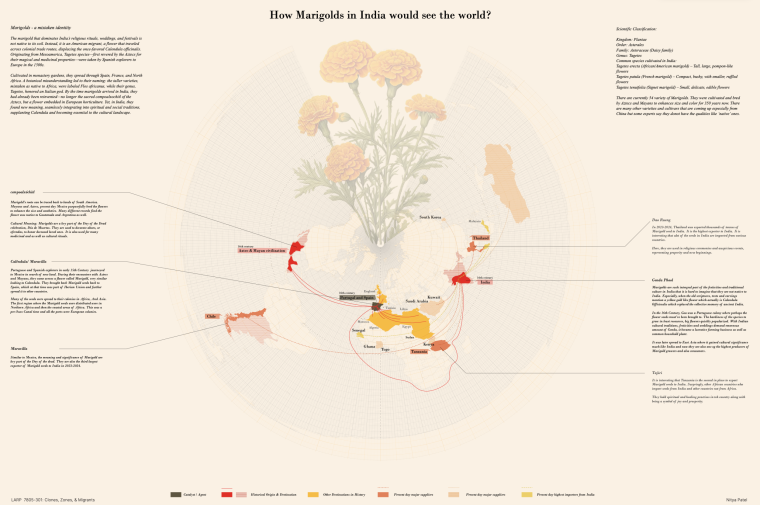

LA+ is the interdisciplinary journal published by the Department of Landscape Architecture. Teams of students work alongside Chair of Landscape Architecture Richard Weller and Editor-in-Chief Tatum Hands to produce each issue. In the most recent issue, LA+ RISK, Bernard Spiegal writes about the inevitability of risk in play. Spiegal is an author and director of PLAYLINK, a multi-disciplinary practice focused on securing children and teenagers’ freedom to play in variety of settings.

Children and teenagers want and need to take risks. They do this ‘naturally’ in the sense that, left to their own devices, they seek out and create encounters that carry degrees of risk or uncertainty. This process of risk-taking necessarily entails exploration, discovery, and learning – about oneself, one’s capabilities, and the wider world. To take a risk is to assert one’s autonomy and power of agency. It is to learn by doing that actions have consequences. It is an aspect of moral education. Play and risk-taking are creative acts. A perspective to bear in mind as we briefly survey the scene.

Here’s a conventional playground: fenced, rubber or synthetic ‘safety’ surface, inert, uniform, dead. Inside the fence are metal swings, slides, and climbing frames. Climbing, swinging, and sliding are the only actions the equipment formally allows. But there are always renegades who will use equipment ‘wrongly’ – climbing onto the roof of play equipment that was not ‘meant’ for climbing, or being upside down on a swing or slide. It’s simple really: children are exercising their sense of agency, their autonomy, their creative capacity to bend even seemingly resistant environments to their own purposes and interests. And the risks they take are generated by their choices, their imaginations, their creativity. The designer, weighted with rule book, restrictive (and often questionable) design standards, and liability anxieties may be part of the problem, not the solution.

But perhaps we should start with rights, rather than design. Spatial rights. In this case, the rights of children and teenagers to be able to roam, use, and loiter around their cities, towns, and villages. Their rights to be seen and heard within shared social space. The right to play. And the concomitant requirement on adults not to think those rights are being accommodated simply by the provision of sequestered, age-defined reservations; that is, playgrounds. Simply saying this, thinking this, reframes the way space and its potential is perceived.

Here’s a new rule: all design briefs that aim to take account of children, teenagers, and families should prohibit the creation of playgrounds. A salutary benefit here would be to force designers to see the entire environment as potentially available to children. To be effective, this would require adults to nurture sensitivity and insight by noticing what children actually do, as distinct from what they may say they like to do when asked in some useless consultation. Recalling one’s own childhood can offer clues in this regard. Readers of this are likely to have been children once.

This is not a technical, apolitical exercise. Rather, it is underpinned by a key value: the need to legitimise children in public and communal space. This is risky stuff, given how teenagers in particular are often negatively perceived, and that’s without considering perceptions and prejudices in respect of race and class.

Children will always like to swing, slide, climb, and there are many ways to provide those experiences, one way being specialist equipment (though it doesn’t need to be in a playground). But the wider, more general point is that the environment as a whole has the potential to be playable space. What curtails that potential is a culture of prohibition combined with a uni-perspective, such that a bench is only for sitting, but not for climbing and jumping. Our attention needs to be directed towards engendering a culture of permission along with a broad view of what constitutes ‘playability.’

This is not to suggest unhindered licence – there is an etiquette of reciprocal and mutual courtesies to be observed by all users of shared space. But the form and meaning this takes is in part governed by whether a culture of prohibition or permission prevails.

Children and teenagers being seen and heard in shared public and communal space is one of the hallmarks of a society at ease with itself. We are not at ease.

Expand Image

Expand Image