March 19, 2018

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

“In landscape architecture today, we have too few intelligent, critical and rigorously developed voices,” said Richard Weller, Meyerson Chair of Urbanism, professor and chair of Landscape Architecture, and co-director of The Ian L. McHarg Center. “We have a lot of good people. We have a lot of good intentions. Design quality is improving all the time … But we still sorely lack articulate critical positions. And if there’s anything that Alan represents, it’s a critical position.”

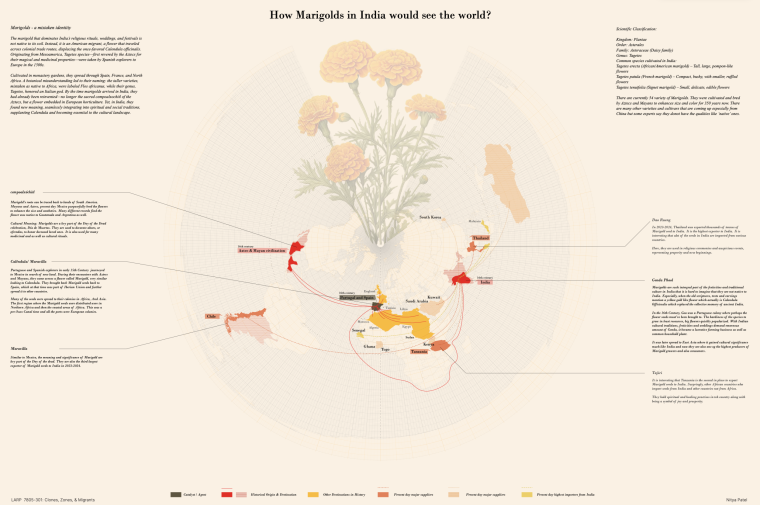

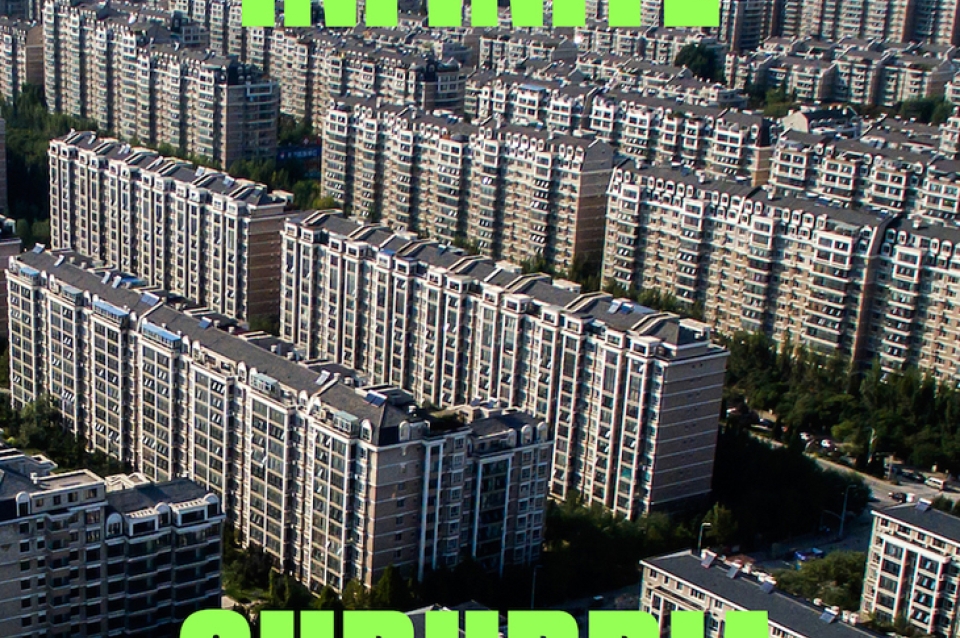

He was introducing Alan Berger (MLA’90), the Leventhal Professor of Advanced Urbanism at MIT and a 1990 graduate of PennDesign’s Master of Landscape Architecture program. Berger, who is also co-director of the Leventhal Center for Advanced Urbanism and director of the P-REX Lab, returned to Meyerson Hall last week for a guest lecture on the topic of the 2017 book Infinite Suburbia, which he co-edited. The book contains 52 essays from 74 authors over nearly 800 pages, and represents a shot at correcting what Berger sees as an imbalance in the design and planning professions: Leading thinkers and practitioners spend most of their efforts on the cores of cities, while globally, populations are moving en masse to their outskirts. Weller turned the lectern over to Berger.

“The sheer magnitude of land conversion taking place on the urban periphery demands that new attention and creative energy be devoted to the imminent suburban expansion,” Berger said. “Suburban models, most of them, are wasteful, unsustainable, and probably also inequitable. However, despite having deep historical roots in conceiving suburban environments, the landscape architecture profession, the planning profession, and other design professions overwhelmingly vilify suburbia and seem disinterested in even significantly improving it.”

Since Infinite Suburbia was published last fall, Berger has discussed its implications for the professions widely in lectures and interviews. In an op-ed in The New York Times titled “The Suburb of the Future, Almost Here,” Berger argued that for all the hype about the millennial generation’s love of the city, most millennials actually profess a preference for the suburbs, albeit a type of suburban living that doesn’t quite exist. The development of drone technology, autonomous cars, and better landscape design would transform suburbs into “smart, efficient and more sustainable places to live,” Berger wrote. The piece generated 562 comments.

“One could extensively argue that urban planners are violating United Nations declarations when we put growth boundaries up around our cities.”

In his PennDesign lecture, Berger took aim at planners’ fixation on density as an urban cure-all. Research collected in the book suggests that no evidence supports the idea that densifying suburbs would create greenhouse benefits.

“This is a topic that smart-growth people never talk about and you should be aware of,” Berger said. “As people become more affluent, they use more energy. This is a well-known law. Economists have written about this time and time again. When you densify suburbs, you make suburbs more expensive to live in, and that attracts people that are essentially going to use more energy. So the whole loop closes in on itself and we have to ask ourselves, why did we do this?”

In making his argument for a renewed focus on suburban development, Berger noted repeatedly that global population trends suggest the future is suburban. Already, 70 percent of the U.S. population lives in suburbs, he said. Australian cities are on track to become unlivable megacities if they don’t allow more decentralized development, he said. He argued that policies promoting centralized density have spurred runaway gentrification. To Berger, the professional focus on urban environments reflects a stubborn disregard of suburban possibilities.

“The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights says that people are free to move within their countries to anywhere of their choosing,” he said. “So one could extensively argue that urban planners are violating United Nations declarations when we put growth boundaries up around our cities. Urbanists may not like the aesthetics of suburbia's horizontal forms. Many of us also don't enjoy the ubiquity of automobiles. But most people are smart, and they will choose with their wallet to make the best decision for their family where they live.”

Before concluding, Berger outlined a speculative day-in-the-life of a future suburb, which provoked a range of responses from the audience of design students and faculty, including questions about inequality, politics, and diversity.

In the vision, a woman wakes up and sends her child to school in an autonomous electric vehicle, which also provides the student with a healthy lunch. She orders a ride for herself, meeting the car on her front lawn, which, because her community is planned around shared storage of autonomous vehicles, is not obscured by a driveway. Arriving at work, she has no need to find parking.

“At her work desk a notification pops up on the window asking if she would like to participate in yoga at lunchtime,” Berger said. “Below the notification, a note indicates how many health insurance points this activity is worth, which also notifies her health insurance provider and doctor, and reduces her rate. She chooses ‘Yes.’ An autonomous van picks up several of the work colleagues and delivers them for the yoga break to an office park setting that is conducive to quiet activities such as yoga. And at the end of a hard day’s work, she enters relaxation mode, available at the luxury level she chooses for the ride home. The seats recline like a beach lounge, a tropical beach theme is chosen on the screen, the interior is transformed into a beach view, with beach sounds through the audio systems, all of the screens now integrating with the windshield into a seamless multi-sensory experience. Enjoy your ride into infinite suburbia.”

Expand Image

Expand Image