March 14, 2024

Designing the Farm of the Future

An interdisciplinary team of Penn faculty and students is developing new models of agriculture to sustain people and planet.

By Matt Shaw

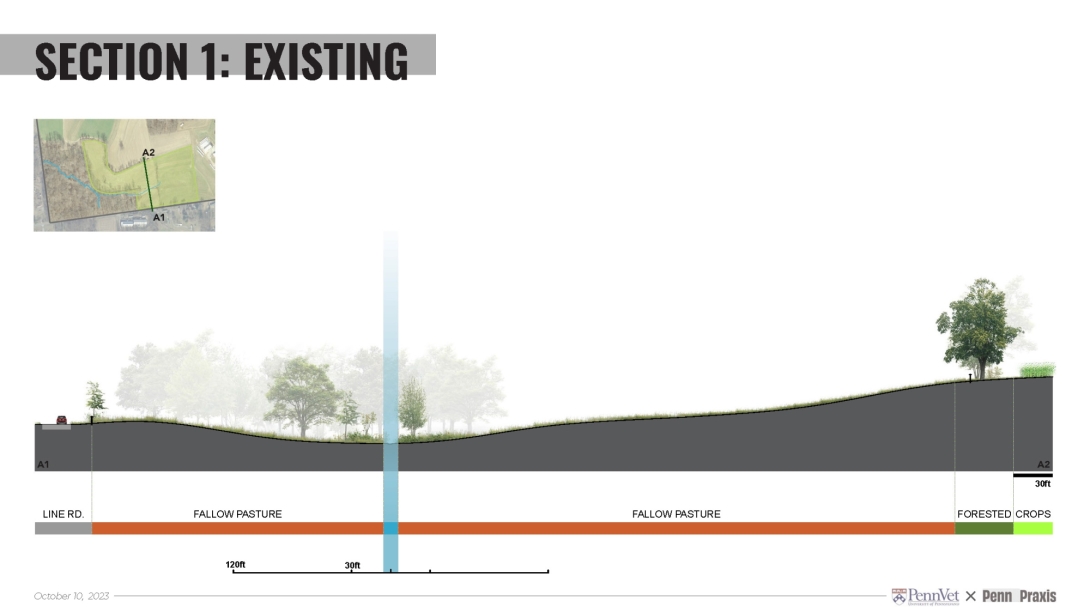

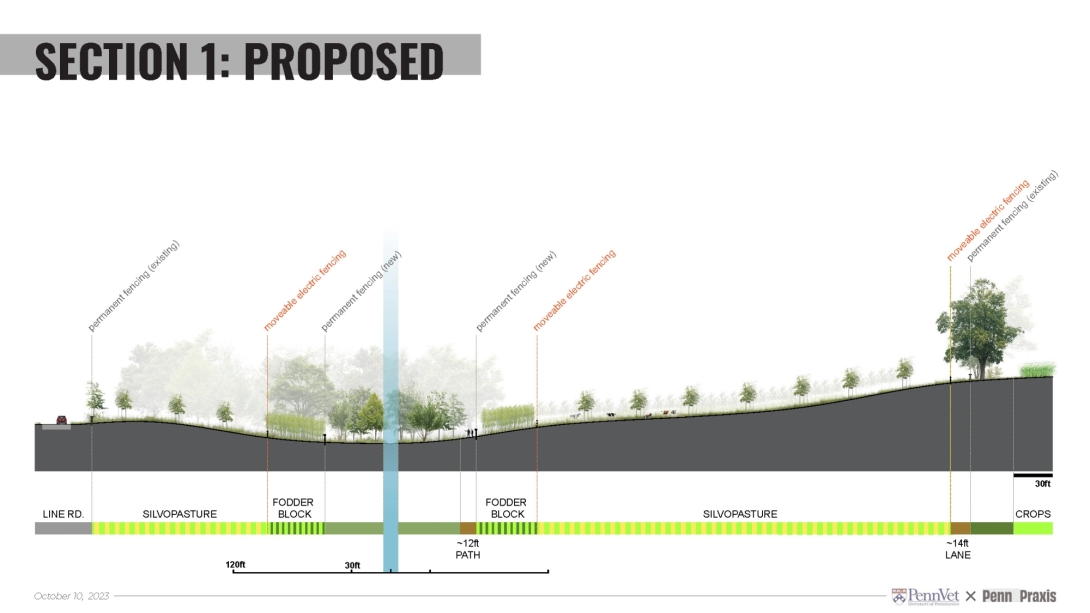

Penn Vet's New Bolton Center is the site of an ongoing collaboration between landscape architects and animal agriculturists that is developing regenerative agricultural landscapes with a goal of improving water quality, land use, ecosystem services, and animal welfare. (Photo Elliot Bullen)

Close

Penn Vet's New Bolton Center is the site of an ongoing collaboration between landscape architects and animal agriculturists that is developing regenerative agricultural landscapes with a goal of improving water quality, land use, ecosystem services, and animal welfare. (Photo Elliot Bullen)

Expand Image

Expand Image