February 7, 2017

Envisioning a Future for “The Most Handsome Station in America”

Figure 1: Southeast elevation facing the Delaware river from the rail viaduct. (Source: PECO, 1930s)

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Figure 1: Southeast elevation facing the Delaware river from the rail viaduct. (Source: PECO, 1930s)

Historic Preservation Studio

HSPV 701-201

What do we do when our largest, most significant, and most marvelous pieces of industrial heritage become obsolete? That was the challenge posed to eight students in the Preservation Studio on Philadelphia’s Richmond Power Station in Fall 2016, led by Professor of Practice Pamela Hawkes. Our solution: to use the building’s greatest assets in a multistage, long-term, “slow” development based on pop-ups, art space, and industrial use with a focus on green energy. The idea was to transform a brownfield liability into a community asset, re-purposing its superb site and immense embodied energy for new enterprises.

Located north of Center City, the Richmond Power Generating Station (1924-25) merged the aesthetic and cultural power of beaux-arts design with latest technology to generate power to run the industries that earned the Philadelphia the title of “The Workshop of the World." Built and operated by the Philadelphia Electrical Company (PECO) and designed by Chief PECO engineer W.C.L Eglin and architect John Torrey Windrim, its monumentality and classical aesthetics intentionally associate technological innovation with notions of permanence and tradition. It was a giant among the region’s power facilities, with a Turbine Hall 125 feet high and generating 100,000 kilowatts of electricity a year. Industry publications called it “The Most Handsome Station in America,” as well as one of the most efficient.

Over time, technology, the environment, and politics changed, and this coal-fed behemoth was converted to gas with Philadelphia’s clean-air act in the 1970s. The station, now owned by Exelon Corporation, was ultimately retired in 1985, during a period when Philadelphia’s population, industry, and employment were at all-time lows. Since this time, the historic buildings have been closed, though accessed occasionally as sets for movies like “Twelve Monkeys” and “Transformers 2.” Buildings have begun deteriorating rapidly over the past decade. The roof is now open to the elements, water pours in and the machinery rusts while urban explorers and graffiti taggers cause more damage with each new break-in. However, the Studio confirmed that the site has great value in its rarity as a complete building with intact machinery that is representative of a complete set of industrial processes picturesquely sited on the shores of the Delaware River.

Figure 2: The ceiling has quickly deteriorated and is now letting the elements inside. (Source: Emily Gruendel, 2016)

Challenges posed by adaptive re-use of a vast monument like this include its location within a sprawling industrial area and the effects of weather on a building that hasn’t seen much use or maintenance in more than two decades. The goal of the Preservation Plan for Richmond Station was to create a “proof of concept” that might encourage for-profit and non-profit stakeholders to develop a more detailed vision, budget and implementation strategy for stabilization and use. After gathering metrics and history on the site’s position in wider Philadelphia, our studio recommended phased redevelopment for the site.

Our research revealed literally hundreds of examples of successful adaptive-reuse projects involving power stations across the world, from London’s Tate Modern and NYC’s Long Island Power House, to Toronto’s Hearn Generating Station. Each had its unique challenges, ranging from scale, integrity, adaptability, location, and historic significance, but the sheer numbers proved unequivocally that not only can these buildings be redeveloped, but that they can help regenerate their surroundings. Philadelphia’s Chester Station, built in the same era as Richmond, has been re-used as offices, while the retired Delaware Power Station, another design by Eglin & Windrim, has been purchased by Bart Blatstein for event space and waterview apartments.

Figure 3: Proposed phyto remediation and integration with proposed Delaware river waterfront trail. (Source: Emily Gruendel, 2016)

We considered a range of interim uses to illustrate the multitude of possibilities that this site holds. They recognized that Richmond is not an urban setting surrounded by rising real estate prices and dense residential/commercial areas, but in fact has been targeted for ongoing industrial development. One idea was to valorize the industrial sublime that this site is so loved for. Much like Eastern State Penitentiary, our designs included guided tours of the incredible industrial processes and architecture. In order to create funds for more immediate stabilization, we explored the possibilities offered by a range of pop-ups, ranging from drive in movie theatres, flea markets, skating rinks, and water recreation to more permanent functions like a Green Energy Research Centre, vertical farming, server farms or other industrial use.

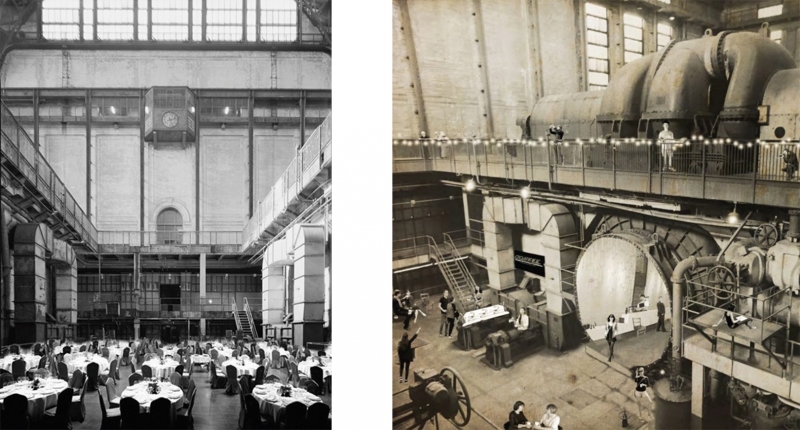

Figure 4: Proposed adaptive-reuse of the central courtyard in the Turbine hall as an (Source: Peter Hiller & Evan Oxland, 2016)

Adopting a flexible strategy with phased development can provide funds for urgent building stabilization, eventual upgrades and site activation. This approach, currently employed for private redevelopments like BOK, the former high school in South Philadelphia, and non-profit sites like Eastern State Penitentiary is fundamentally experimental, but also seems inevitable where capital is small and degrading assets are vast. It gives strategies more breadth to flourish and thus prove their viability.

--Evan Oxland, MSHP ‘17

For more information regarding this site, and other sites of its ilk, Assistant Professor Aaron Wunsch has recently published a book on PECO’s formidable collection of beaux-arts Palazzos of Power.