September 5, 2017

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

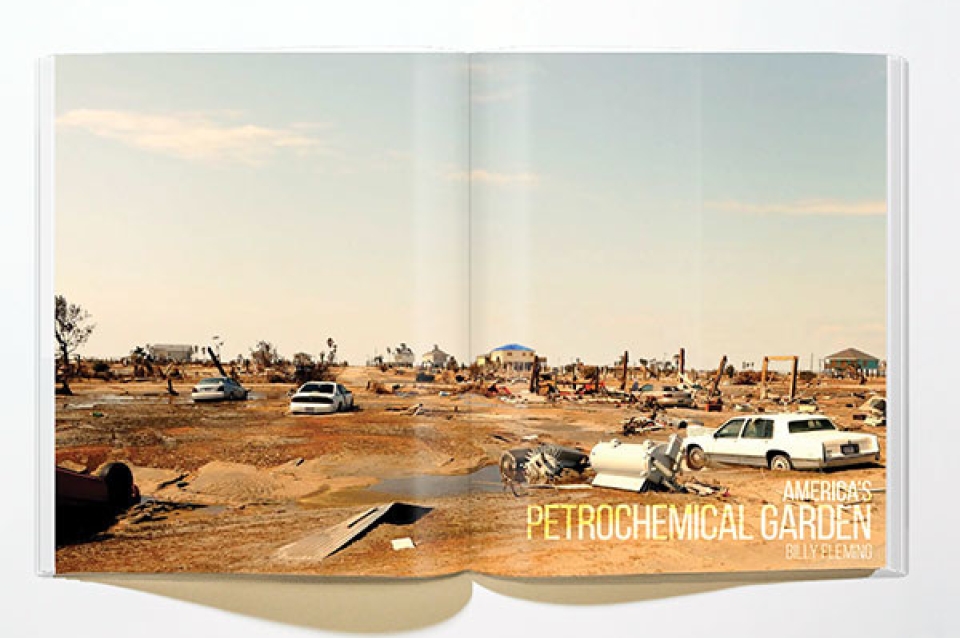

LA+ is the interdisciplinary journal published by the Department of Landscape Architecture. Teams of students work alongside Chair of Landscape Architecture Richard Weller and Editor-in-Chief Tatum Hands to produce each issue. In the most recent issue, LA+ RISK, Billy Fleming (PhD’17), research coordinator at the Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology, writes about a city he studied in depth for his thesis.

On September 14, 2008, the Galveston Bay region lay in ruins. Three-quarters of the island’s homes, businesses, and other structures lay scattered across the salty brine remnants of Hurricane Ike. The low, undulating dune system that once rimmed the seaward edge of the Texas coast was now imperceptible. A clear path of erasure stretched from the beaches of Galveston Island to the Houston suburbs of Kemah and Baytown. Fish flopped and snakes—hordes of them—slithered across FM3005, the westward evacuation route washed out long before Ike made landfall. By the time the insurance agents and actuaries finished surveying the aftermath, Ike’s damage toll rose to almost 150 billion dollars. Mostly absent from the discourse on landscape architecture and resilience, Hurricane Ike stands as the second-most destructive storm in US history.

That’s because on September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and became the opening salvo of the global financial meltdown known as the Great Recession. As a result, the national press and the federal government quickly pivoted away from the work of disaster recovery in Galveston Bay and towards staving off a national economic collapse. This left the region’s residents without the attention or the resources that typically flow in the aftermath of a storm. Nearly a decade later, the region has largely recovered from the worst of Ike, but over the course of that decade, little has been done to deal with the surge and sea level rise related risks facing the region. The region remains one of the nation’s most vulnerable territories.

Galveston Bay and its distributaries—the San Jacinto, Buffalo Bayou, and Trinity Rivers—represent the largest ecological system within the nation’s fourth-largest and fastest-growing urban region, the Houston metropolitan area.1 More than six million people reside in and around the Houston-Galveston region. Half of those residents occupy a marshy surge zone encircling the Bay. There, a sprawling patchwork of tract homes and wide, winding roadways blanket the low-lying, flood-prone landscape of Houston. Though the presence of these homes in the surge zone is a problem unto itself, their vulnerability is complicated by the lax land development regulations in Houston and its suburbs. These homes were developed in a flood-prone environment according to building codes that do not consider flood-proofing or free-boarding in their stipulations. Seasonal flooding already imperils these homes and residents each spring.

The rationale behind building cheap homes in a flood-prone landscape is clear. The suburban communities encircling Houston were simply vying for their share of the region’s booming population. Spurred on by the growth in oil and petrochemical industries over the last two decades, Texas City, Kemah, League City, Baytown, and others each hoped to capture a larger portion of the property tax receipts these new residents would provide. In Texas, where property taxes are very high in order to offset the absence of a statewide income tax, this led suburban communities to compete in a race to the bottom for new residents.2 Nowhere was this process more evident than in the surge zone surrounding Houston. There, cheap land and cheap housing coalesced to pack hundreds of thousands of new people into a high-risk landscape.

The magnet that has drawn—and continues to draw—so many people to the Houston region is the booming petrochemical industry headquartered in and around Galveston Bay. Multi-billion dollar investments in oil refining capacity, petrochemical processing and storage, and port infrastructure constantly push the region’s center of economic gravity towards the water’s edge.

The region already boasts the largest cluster of petrochemical activity in the nation, with nearly 30% of all domestic refining capacity operating in and around the Bay.7 It is the petrochemical capital of the United States, if not the world. It’s also home to the nation’s second (Houston), fourth (Beaumont), thirteenth (Texas City), eighteenth (Port Arthur), and forty-ninth (Galveston) largest ports by tonnage in the US.8 All of these port facilities are expected to grow as a result of the Panama Canal expansion.9 Many of them also abut, intersect, or otherwise conflict with the sprawling patchwork of suburban homes that characterize the region.

As a result, the residents of Galveston Bay face more than the risk of flooding. They face the risk of exposure to the petrochemical slurry being stored and refined alongside their neighborhoods. They face the risk of being left with a toxic, uninhabitable community in the aftermath of the next storm.

Notes

1 “Major storms make landfall in the region once every eleven years” Federal Emergency Management Agency, “Disaster Declarations by Year,” https://www.fema.gov/disasters/grid/year.

2 Texas Engineering Extension Service (TEES), “Hurricane Ike Impact Report” (2012), http://thestormresource.com/Resources/Documents/Full_Hurricane_Ike_Impact_Report.pdf.

3 Interview with local elected official, Galveston, TX (March 21, 2016).

4 TEES, “Hurricane Ike Impact Report.”

5 Houston-Galveston Area Council, “Regional Economic Development Plan,” http://www.h-gac.com/community/gcedd/regional-economic-development-plan.aspx.

6 Jaime Masterson, et al., Planning for Community Resilience: A Handbook for Reducing Vulnerability to Disasters (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2014).

7 Greater Houston Partnership, “Houston’s Economy,” http://www.houston.org/economy/index.html#Energy.

8 Bureau of Transportation Statistics, “Tonnage of Top 50 US Water Ports, Ranked by Total Tons,” http://www.rita.dot.gov/bts/sites/rita.dot.gov.bts/files/publications/national_transportation_statistics/html/table_01_57.html.

9 Brian Davis, Rob Holmes & Brett Milligan, “Isthmus: Panama Canal Expansion,” Places Journal (2015) https://placesjournal.org/article/isthmus-panama-canal-expansion.

Expand Image

Expand Image