February 17, 2025

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

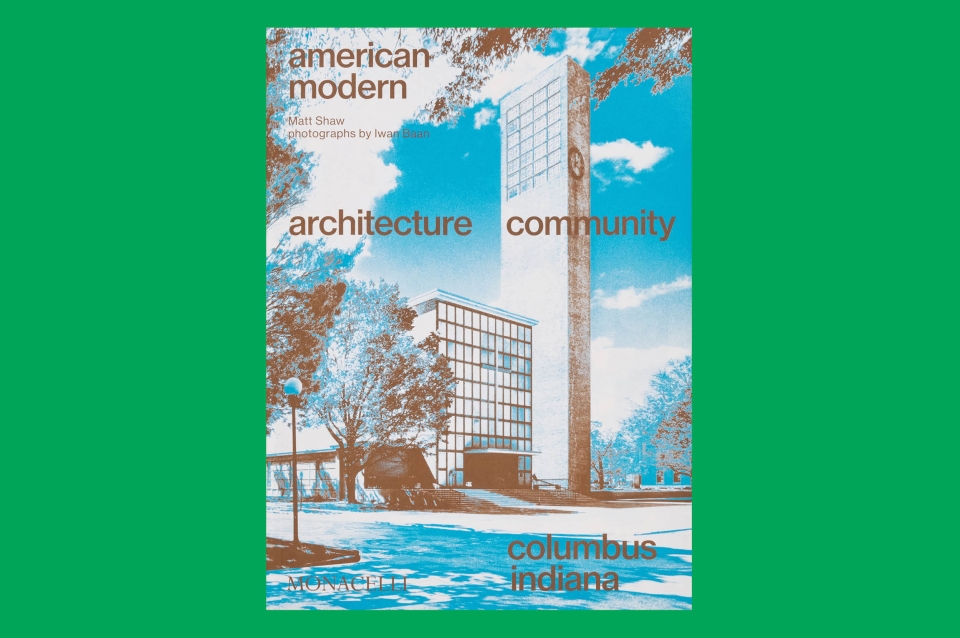

Despite its relatively small size, Columbus, Indiana, is now recognized as a significant architectural destination because of its long roster of Modernist buildings commissioned from some of the most famous names in the field. The story of how this collection of masterworks came to be is told in a new book, American Modern: Architecture; Community; Columbus, Indiana (Monacelli, in association with Landmark Columbus Foundation), by architecture writer and Lecturer in Architecture (and Columbus native) Matt Shaw. In an excerpt from the book, which includes photographic documentation of dozens of buildings by Iwan Baan, Shaw details how a plan for a design competition for a new elementary school led the way for the city to create an architectural plan to guide future planning.

Completed in 1957, Lillian C. Schmitt Elementary School is a modern, progressive school building that captured the spirit of the modern, progressive city Columbus wanted to become. Built to modernize education around the county—Bartholomew County was working to replace its one-room schoolhouses, many of which did not have running water or electricity—standard structures such as Columbus High School were quick to construct, but repetitive and institutional in feel. Since schools were the first time Columbus children were exposed to public architecture, Cummins leadership felt they should be inspiring spaces to foster a spirit of lifelong learning. Company leadership also noted that schools were one of the first things prospective employees asked about when touring Columbus.

In a departure from the more standardized approach to school building, Lillian C. Schmitt Elementary School was built from brick and wood and featured thirteen open-plan classrooms, each with its own play space and a strong visual connection to the outdoors via large windows. Roof-like gables over classrooms reflected the Progressive Era quest to make education spaces more homelike. Details such as door handles and built-in furniture were sized to children’s proportions. The small scale and warm materials were considerations that sprang from the philosophy of the Crow Island School in Winnetka, Illinois, designed by the Saarinens with Perkins, Wheeler & Will and built in 1940. It was among the most progressive in the country, both for its facilities and the innovative ideas about education they embodied. Weese would have been aware of this connection.(1)

Harry Weese/Harry Weese Associates, Lillian C. Schmitt Elementary School, 1957 (Photo: Iwan Baan)

Schmitt was seen as a resounding success by both the school board and teachers, as well as the parents and the community at large. With this, the pieces were in place to officially launch the CEF Architecture Program, which would see the company take more of a lead in driving building projects. Cummins extended a new offer to the school board in 1957, offering to pay for architects’ fees if the board would choose from its expert-recommended list. This offer would eventually be extended to all public agencies in accordance with nonprofit laws. The system was based partly on Saarinen’s familiarity with the US State Department’s Foreign Building Office (FBO) and its three-person advisory committee, originally Rudolf M. Schindler, Bruce Goff, and Pietro Belluschi (dean of MIT’s School of Architecture). For Columbus, Saarinen chose Belluschi and Doug Haskell, editor of Architectural Forum, to join him. Many of the architects selected for Columbus had designed embassies for the FBO.(2)

The foundation would provide a new list of six or more architects chosen by a “disinterested,” or unbiased panel (in the beginning it was Eero Saarinen and Pietro Belluschi) for each project. The architect would be given at least twelve months to “plan, design and make working drawings,” and would be responsible for the building, interior finishes, and furnishings, and recommending landscaping, “so that the building, inside and out is planned and designed in aesthetic harmony.”

In a 1957 letter to Columbus school board president W. L.Wiseman, [J. Irwin] Miller explained:

Every one of us lives and moves all his life within the limitations, sight, and influence of architecture—at home, at school, at church, at work. The influence of architecture with which we are surrounded in our youth affects our lives, our standards, our tastes when we are grown, just as the influence of the parents and teachers with which we are surrounded in our youth affects us as adults. American architecture has never had more creative, imaginative practitioners than it has had today. Each of the best of today’s architects can contribute something of lasting value to Columbus.(3)

It was this focus on value from a very pragmatic, if somewhat metaphysical, stance that defined the Columbus architectural project from the start. Rising construction costs made it imperative to build immediately, imagine projects past present needs, and produce outcomes with lasting quality. “It is our feeling that the plan would have the following merits,” the letter continued, stating:

- It would not increase the costs of any new building and might even reduce them.

- It would greatly increase the quality of buildings and would probably extend by many years their useful life.

- It would attract and stimulate the best work of the best architects, for the work of each would have to stand the challenge and comparison of the work of his best competitors.

- It would contribute to the quality of Columbus’s educational program and be a real aid in attracting the best teachers and administrators.

- It would cause favorable national attention to be drawn to Columbus and would help in attracting good people to Columbus in all capacities.(4)

Saarinen’s list of six recommended designers for Columbus Village and Cummins’s offer to pay the fees for a first-class architect would crystallize into the program as it is known today. By 1961, it had been more than twenty years since Eero Saarinen had come to Columbus with his father for the completion of the First Christian Church—a marvelous coincidence, as Miller wrote later.(5) Yet whereas in the 1940s and ’50s, Columbus leaders were simply solving community problems and pragmatically enlisting Saarinen and Weese to help them, now they had figured out how to engage with design at its highest levels while promoting community participation. A major triumph of selling the school building program came in 1959, when the state tax board agreed to a proposed one-dollar increase to fund school buildings.

1) Alexandra Lange, “The Shape of Schools,” Exhibit Columbus symposium 2016.

2) Amy Marisavljevic, “Columbus, Indiana: Eero Saarinen’s Legacy A Thesis” (MS Historic Preservation Ball State University, May 2012), 54.

3) J. Irwin Miller letter to Bill Wiseman, November 29, 1957, Irwin Sweeney Miller Family Collection 188/2.

4) Ibid.

5) J. Irwin Miller letter to Charlies R. Stoy, December 7, 1971, Irwin Sweeney Miller Family Collection 178/1.

Expand Image

Expand Image