July 17, 2025

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Tags

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

A new book from Oxford University Press, Constructing Utopias: China's New Town Movement in the 21st Century, by Zhongjie Lin, the Benjamin Z. Lin Presidential Professor of City & Regional Planning and faculty director of the Future Cities Initiative, documents the last four decades of Chinese urbanization and the diverse ways that the country has approached city building. In an excerpt from the book’s introduction, Lin relates his own experiences of seeing the dramatic transformation of Shanghai’s Pudong district, which for Lin illustrates the complex realities brought about by the New Town Movement throughout China.

I moved to Shanghai for college in 1990. A small-town boy from a southern province, I had since heard countless relatives and schoolmates echo this local adage: “Choose a bed in Puxi over a house in Pudong.” Puxi, or West Shanghai, encompasses the city’s historic districts centered around its colonial-era heart. Across the winding Huangpu River in the south and east is a rural expanse called Pudong, meaning East Shanghai. No bridges, only a couple of outdated tunnels, connected the two then. In contrast to its cosmopolitan sibling, Pudong was countryside, dotted with villages, farms, factories, and some workers’ communities. Many of its roads were unpaved. For Shanghainese, the distinction between Puxi and Pudong was as clear as day and night.

During my decade in Shanghai, first as a student then an architect, I witnessed Pudong’s dramatic transformation. In the wake of the 1989 political upheavals, China faced domestic challenges and international sanctions, potentially disrupting the country’s modernization and economic reforms. In response, Deng Xiaoping, then China’s de facto paramount leader, announced the pivotal national initiative of “Developing and Opening up Pudong” in 1990. This ambitious initiative established three anchor zones: Lujiazui as a financial center, Jinqiao for export-oriented manufacturing, and Waigaoqiao as a free trade zone. At the same time, construction of two large cable-stayed bridges commenced, connecting Pudong to Puxi. In few decades, a new global city rose in the east.

Old neighborhoods being demolished in Pudong, with skyscrapers of the new Lujiazui Financial District rising in the background, Shanghai, 1996. (Photo by Mark Henley/Panos Pictures).

Today, Lujiazui’s towering skyscrapers form a dazzling skyline, positioning Pudong not only as a formidable rival of the prosperous historic Puxi district but also as a potent symbol of the tremendous economic energy that has emanated from China. The new district epitomizes the nation’s urban transformation, marked by territorial expansion, demographic shifts, and rapid wealth generation as China integrates into the global economy.

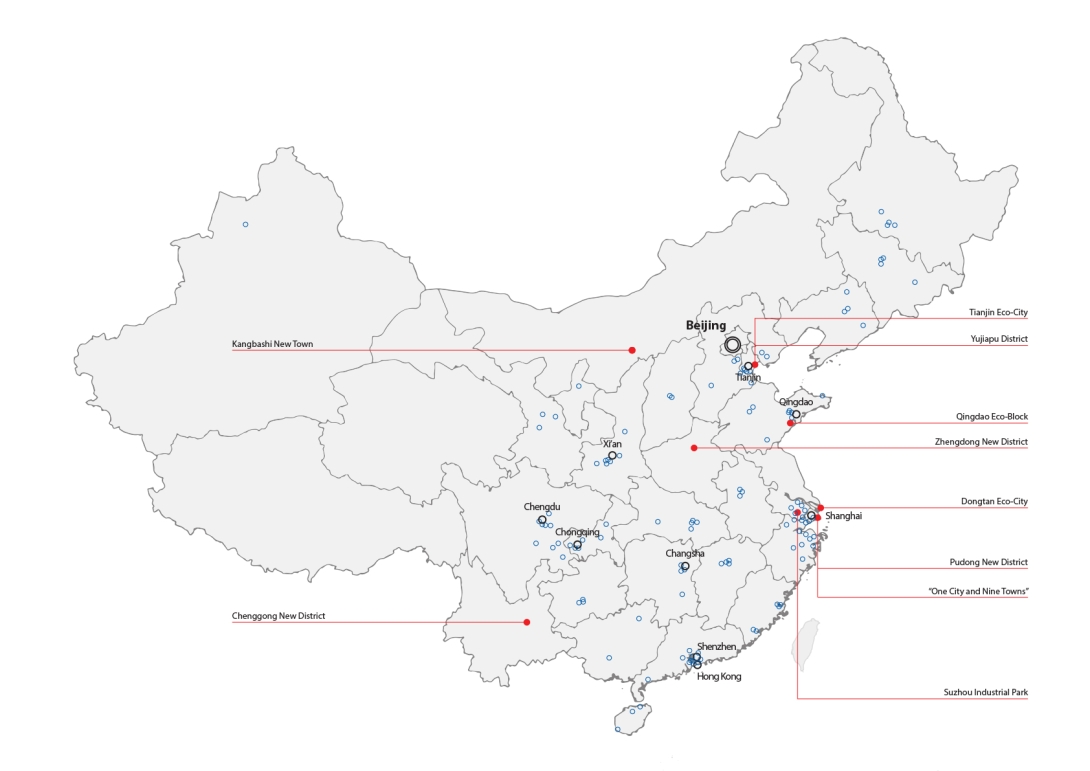

Pudong’s development offers a microcosm of China’s broader urban transformation since urbanization accelerated in the 1990s. Master-planned new towns and districts have sprouted across the country, from the affluent east and south coasts to the mountainous west and black-soil northeastern plain. In 2005, a Xinhua report announced the central government’s plan to build 20 new cities annually for 20 years.(1) In 2019, when the China Academy of Urban Planning and Design (CAUPD) concluded a three-year survey, it revealed that 3,845 new towns and new districts have been created nationwide, including 570 initiated by the central government, 1,991 by provincial governments, and 1,284 by local governments.(2) These new towns average 37 km2 and are planned to accommodate 110,000 residents each. If fully realized, they could house over 426 million people, nearly a third of China’s current population.

Locations of notable Chinese new towns studied in Constructing Utopias. (Graphic by Yin Yihan).

Where will all the residents come from? Apart from developing new towns, existing cities have also experienced significant growth, with skyscrapers proliferating. This exponential expansion cannot be solely attributed to birth rates, given China’s strict one-child policy, enforced from 1979 to 2015. The much slower population increase reported in the 2020 census suggests an imminent population decline.(3) Most governmental officials, planners, and economic analysts believe that the surge in demand for urban space is primarily driven by unprecedented rural-to-urban migration. By 2019, approximately 291 million rural workers—nearly the entire US population—had migrated to cities, often bringing their families, even though their Hukou (household registration) remained in the countryside.(4) This massive migration propelled China’s urban population from less than 20% in 1980 to over 60% in 2020, averaging 14 million new urban residents annually for four decades.(5)

Characterized cogently by economic geographer David Harvey as the “largest mass migration the world has ever seen,” China’s urbanization has proceeded in tandem with its rapid industrialization.(6) The former plays an instrumental part in the latter by supplying a massive labor force that has propelled China to the world’s second largest economy and transformed it from an agrarian nation to a global manufacturing powerhouse and technological leader. China’s economic transformation has, in turn, reshaped its social and demographic landscapes, creating a substantial and still growing urban middle class, estimated at 430 million by 2017.(7)

This fundamental urban transformation has resulted in an extended housing boom, lasting over three decades, and effectively stimulated domestic consumption and broader economic growth in a similar way as the housing boom in the post-World War II United States. China’s urbanization has also seen global repercussions, evident in its massive export and surging international tourism, as well as increased demand for raw materials, like iron ore and oil, and advanced machinery, like aircraft. As economist and Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz predicted, China’s urbanization has emerged as a primary driver of the global economy in the 21st century, alongside technological innovation in the United States. Some scholars even posit that cities themselves have become the most significant output of the Chinese economy since the millennium.(8)

1) Jean-Pierre Langellier and Brice Pedroletti, “China to Build First Eco-City,” The Guardian, May 7, 2006, accessed Apr. 22, 2024.

2) China Academy of Urban Planning and Design, “‘Quanguo xincheng xinqu guihua jianshe guanli baipishu’ zhuyao faxiang yu zongyao jielun” [Primary Findings and Important Conclusions of the “White Paper for the Construction and Management of New Towns and New Districts in the Whole Country”], Urban Planning China, Nov. 6, 2019, accessed Nov. 12, 2020.

3) The 2020 national census reported a population growth of 5.38% during 2010–2020, but there has been widespread suspicion that the actual number might be lower, or even negative. Two months after the publication of the census, the national government announced a new policy that permits and encourages a third child for each family. National Bureau of Statistics of China, “Main Data of the Seventh National Population Census,” May 11, 2021, accessed Nov. 25, 2021.

4) China Labour Bulletin, “Migrant workers and their children,” China Labour Bulletin, May 11, 2020, accessed Nov. 13, 2020.

5) A 2009 World Bank report estimated 17.7 million annual population increase in China’s cities; a 2014 national survey recorded the number of annual rural-to-urban migrants at 16 million, and that urbanization reached 54.8% countrywide. The World Bank, “Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City: A Case Study of an Emerging Eco-City in China” (Technical Assistance (TA) Report), Nov. 2009, p.1; National Bureau of Statistics of China, “Statistical Communique of the People’s Republic of China on the 2013 National Economic and Social Development,” Feb. 24, 2014, accessed Nov. 20, 2020.

6) David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 127.

7) Salvatore Babones, “China’s Middle Class is Pulling up the Ladder behind Itself,” Foreign Policy, Feb. 1, 2018, accessed Nov. 13, 2020.

8) Max D. Woodworth and Jeremy L. Wallace, “Seeing Ghosts: Parsing China’s ‘Ghost City’ Controversy,” Urban Geography 38, no. 8 (2017): 1279.

Expand Image

Expand Image