July 18, 2025

The Making of Weitzman Hall: The Penn Campus

By Michael Grant

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

As the Weitzman School of Design prepares to open its first new building in more than 50 years—an interdisciplinary hub for research and teaching in the historic heart of Penn’s campus—for the Fall 2025 semester, Weitzman News gathered members of the design and construction teams to talk about the making of Stuart Weitzman Hall. This conversation included Weitzman Dean and Paley Professor Fritz Steiner (MRP’77, MA’86, PhD’86); Stephen Kieran (MArch’76), co-founding principal at KieranTimberlake; and Mark Kocent (MCP’91), University Architect. All three are Penn graduates. The building’s history and adaptive reuse will be the subject of an exhibition in early 2026.

Fritz Steiner: It’s threefold. First, it’s a collection of important architecture, and we allow the architects to do a very high level of design without a lot of the constraints that exist on some other campuses. And then, there’s been a very long-term commitment to the campus landscape and its trees. So there’s a real balance, which is closely coordinated by the campus architect and the rest of his team and the campus landscape architect.

Mark Kocent: A number of years ago, we worked with the University Trustees to document a series of stated design guidelines. They are not very prescriptive: basically, we encourage architects to do buildings “of their time.” So, unlike a UVA that has a Jeffersonian approach—think red brick and white trim—or other schools that have a predominately gray stone palette, Penn’s approach has been a consistent focus on contemporary presence; ever since these Design Guidelines were developed by then University Architect Charlie Newman and Senior Vice President of FRES Omar Blaik

From the time when College Hall was built, Penn’s buildings have reflected the leading architectural design and customs of their time, exploring innovation when possible. Much like Penn’s art collection, which is carefully reviewed, the same goes for our built environment. This is architecture of its time, that not only meets a programmatic need, but also advances the evolving theory and the practice of architecture.

Stephen Kieran: Among urban universities in the US, it’s got to be one of the best campuses for this reason. It’s got a landscape thread all the way through it from east to west—Locust Walk and Smith Walk—that’s continuous and different at every sector of the campus that it bifurcates. And it sits pretty much right in the middle of two parallel lines of the campus extending (almost) from the river well to the west. There’s some increasingly positive attention to urban streetscape making on the edges of the campus, and yet a true campus threaded through the middle of it with a remarkable suite of buildings and landscapes along it.

And the Weitzman School of Design, if you look at the whole of that, now sits at a really prominent position pretty near the center, if you consider College Hall the center. This building really makes the Weitzman into a little mini campus within the campus. You’ve got Meyerson, Fisher Fine Arts, and Morgan, now Weitzman Hall, at the apex of that triangle on the opposite side of 34th—a really important moment in the entire campus.

One thing that was on all of our minds was, “How could we improve Smith Walk?” It’s got some big buildings along it that are elevated above the ground, not very many doors, and the doors aren’t all that active. When you enter it now from across 34th Street, it’s got life, the landscape and the steps and the seats spill from the building down to the walk. The spaces at the ground level are public spaces visually open and otherwise open. I think it’s going to make a huge difference to the life of the campus at that very critical juncture.

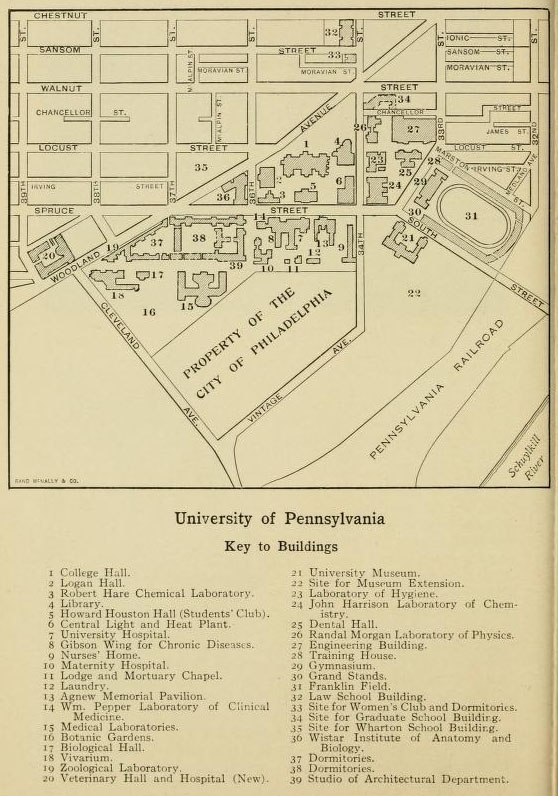

The historic precinct of Penn's campus as seen in a map published in 1915 (Philadelphia Guide to the City and Environs, Rand McNally & Company)

Mark Kocent: When you stand at the intersection of Smith Walk and 34th Street, it’s remarkable because to your north you have KieranTimberlake’s new building and two eras of Cope & Stewardson, Morgan Hall in monochromatic red brick and terracotta and their popular collegiate Gothic expressed in the Towne Building. To your right, you have Edgar Seeler’s Hayden Hall, which has roots in a Richardson’s Sever Hall at Harvard, and then behind you have Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates Roy and Diana Vagelos Laboratories, and then across the street you have the Frank Furness masterpiece, Fisher Fine Arts Library. It’s a wonderful collection of Philadelphia architectural history.

Along with commissioning buildings of their time, another part of our guidelines is encouraging contemporary use of materials, but also contextually appropriate. I think KieranTimberlake did a phenomenal job with their contextual match of this new contemporary building set in a historic setting. It’s going to feel new and yet completely comfortable, almost like it was always meant to be here.

Fritz Steiner: Yes, I would point to the scale of the building, making it fit. Even though it’s a sizable insertion, it doesn’t go too high. There was a lot of work on just the volume that it would occupy. And before with the retention or with the base, the stormwater collection being underground, it limited the kind of vegetation that could occur. So although there is less green surface in the new scheme, there’s more greenery. Along the walk between Towne and Weitzman Hall, it’s going to be loaded with plants. And then, wrapping around on Smith’s Walk, there are generous terraces. It becomes a much more inviting and functional and even greener open space than was there before.

Stephen Kieran: I really think of that as a porch literally on Smith Walk. It literally is kind of a new urban type on that part of the campus.

Mark Kocent: The one thing we don’t want to do is undervalue a site, since its unlikely to come back one day and add an extra story. If I recall, Stephen, you wanted even a little bit more bolder presence on Smith Walk and maybe the budget pushed back a few feet there. I think the building always wanted to step out. In order to fit the program, the new building had to be a little bit longer versus wider. So there was a lot of discussion about the south side of this building and what it was doing to the open space along Smith Walk and what that would feel like.

Stephen Kieran: We certainly needed the space, but I think it’s been a real positive, in the end, for the building. It pretty much aligns with the edge of the adjoining engineering building [Towne], so it’s not out much further, but it really feels like a new building and something you could see the moment you cross 34th Street.

The original Morgan building, in form, is inwardly focused. Our addition is a bit more extroverted. I think it makes a good pair, and it also really permeates the accessible entry. It doesn’t feel like it’s a side entry now, it’s at another front, which is really important.

Fritz Steiner: Penn is largely a brick campus, and one of the beautiful things about the interior of the old building is just having the bricks exposed. It’s going to add an incredible amount of richness to the new space that KieranTimberlake has created in the classrooms and in the offices and the studio, a very rich use of the old brick. For the new brick, Steve found a beautiful, handmade Danish brick [from Petersen TEGL]. When they fire them, the temperatures vary, which creates different shades and textures on the bricks. And while they’re from Denmark, they’re also quite environmentally responsible. It has touches of red and touches of gray which, I think, will give it staying power will make this a distinctive building for centuries to come.

Stephen Kieran: Our spatial model for the addition was a highly flexible loft structure, so there are no internal columns except for the passage in between the two buildings. It’s a clear span. Two floors of the addition are partitioned as studios for fine arts students, with some portions of them also easily repartitioned as offices. And the top level is an open-span classic design studio for architects and landscape architects and others. I think that was a model that artists have long adopted and made their own and has proven to work across time.

Part of how you do that is to have some continuity of the windows, in order to be as flexible as you can about the uses. In buildings like [KieranTimberlake’s] office, there are strip windows that extend the full length. At Weitzman Hall, for artists that don’t want [daylight], there are blackout shades. If, in 15 years, they want to turn the individual studio spaces into communal space, it’s easy to do. If they go the other way, and put more compartmentalization in it, that too is easy to do. The windows are largely concentrated on the east wall and to some extent on the west wall looking out at the Morgan building; the north and south walls are somewhat more opaque. We tried not to do a curtain wall here—we just felt that from the outset that didn’t make sense for a design school. It can be uncomfortable, and from the outside, it doesn’t look very appealing because furnishings are right up against it.

Mark Kocent: With [the former] Morgan building and the Lerner Center to its north, you had two buildings that were built in the late 1800s as the Foulke and Long Institute for Orphan Girls of Soldiers and Firemen. Morgan served as the classroom building [for the orphanage], whereas Lerner was the orphanage’s residential building. So the windows on Morgan were larger and the floor heights were different proportions.

Stephen Kieran: Programmatically, the uses that really work in the [former] Morgan building are quite different than the uses that work really well in the new building. The Weitzman School has a real diversity of need that I think the combination of the two buildings really suits. You couldn’t almost do it new and have it work as well. It’s got a little bit of everything, from research areas to classrooms to faculty office spaces to studio art spaces to design spaces to various centers and archives.

Mark Kocent: Philadelphia has a tremendously rich history with pressed brick, which has a lot to do with the clay that was available in this region. When that clay was fired, iron oxide and different chemical reactions occur, creating the distinctive Philadelphia rust brick color. When it came to bridging the red and brown of the Morgan building and the Towne Building, the brick that KieranTimberlake found was just a phenomenal blend of the two.

Another example of continuity is how KieranTimberlake used a prominent cornice, reflecting what Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates did across Smith Walk on the Vagelos Labs, while also honoring the heavy cornices that Cope & Stewardson created on Morgan. When you look up and see the prominent roof ledge projecting south along the top of Weitzman Hall you may wonder, “Why is that five feet wide?” But the Morgan and Music buildings have these similar wide rusticated corbels holding up a very accentuated soffit. So, when you look closely, you can see there is a lot of subtlety in this building that is contextual with its neighbors in this precinct.

(Construction as of January 2025; video courtesy Target Building)