May 29, 2017

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

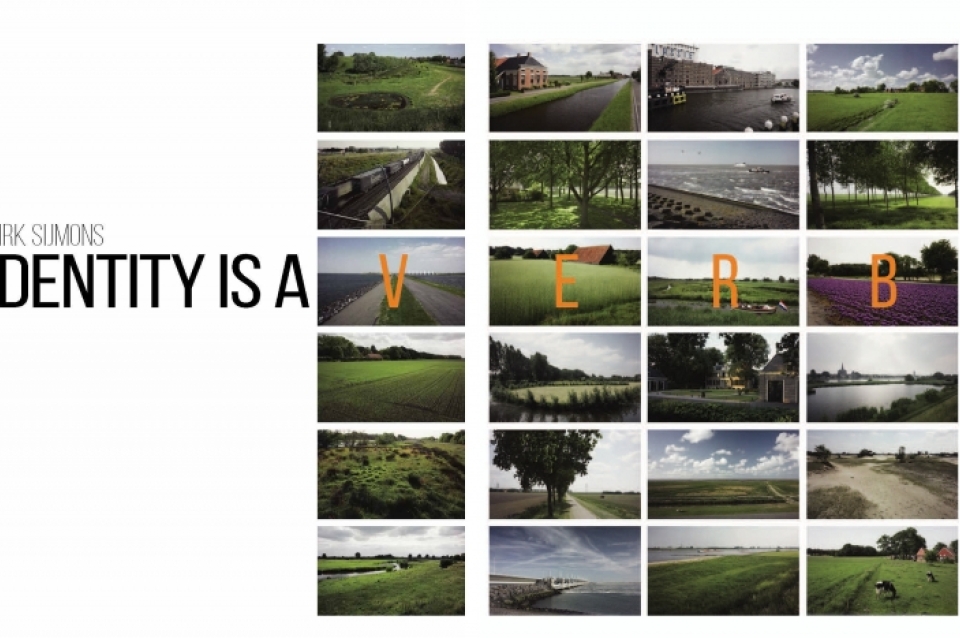

The latest issue of LA+, the interdisciplinary journal published by the Department of Landscape Architecture, is devoted to critically exploring the nexus between place and identity. Ever since the 18th century, when Alexander Pope advised his peers to “consult the genius of place,” the idea that designers could interpret and then express the essential identity of a place has been venerated in landscape architecture. In this excerpt from his contribution to LA+ Identity, Dirk Sijmons reflects on how for centuries the Dutch have collectively shaped their nation’s landscapes as a continuing work in progress.

Around the turn of the millennium, one of the Dutch newspapers asked readers to nominate their ‘artwork of the century.’ As could be expected Rembrandt rated well. Remarkable for me, however, was the small group of readers who nominated the Dutch landscape itself. They argued that it is the only collective work of art we have been working on for the full millennium. But that landscape is also one of the national imagination because the rate of change to the Dutch landscape has been dramatic. What was a differentiated and small-scale agricultural landscape has been transformed into a modern, economic machine. Urbanization and infrastructure changed Holland into an urban landscape and wedged it into the broader economic context of Northwestern Europe. This artifact, formally known as the city, is a conglomeration of built-up areas, water systems, leisure parks, airfields, nature reserves, industries, intensive food production areas, parks, and mining areas all interwoven with tangles of infrastructure, transportation, and both old and new ecological corridors.

There are typically two different Hollands in the collective imagination: a modern agricultural landscape and an urban landscape.

Although it is common for theorists of the city now to absolve any boundary between city and country, in Holland, where you would expect this to be most true, there is still significant differentiation. As such there are typically two different Hollands in the collective imagination: a modern agricultural landscape and an urban landscape. Both ways of seeing are still legitimate because of the specific post-war history of the Netherlands. From 1945 to 1990, national planning policy kept the urban and the rural domains separate and curtailed sprawl. The Netherlands had to be reconstructed after WWII and the housing shortage and lack of building materials could only be met by building mass (modernist) housing in close vicinity to the existing cities. Suburbanization was out of the question. The second important element of post-war policy was the modernization of agriculture to provide cheap food so the wages could be relatively low and re-industrialization could take off. This modernization was an operation of unprecedented magnitude. In the heyday of the reconstruction, each year some 250,000 ha of the countryside was somewhere in the analysis, preparation, or execution-phase of the procedure. The high standard of Dutch spatial planning culture provided that all re-allotment, urban, and infrastructure plans were assisted by institutional design where landscape architects, architects, and urban planners played a significant role in creating these new, scaled up, modern landscapes.

On the one hand, Dutch landscape architects founded their plans with geological, ecological, and cultural historic analysis that represented the genius loci, but on the other hand, they were giving form to the modernization operation that involved generic strategies and techniques that work to eliminate the limitations of the place. Scaling-up, draining, mechanization, fixing ground-water tables, land re-allotment, leveling of lots, new farms and road infrastructure, removal of non-functional landscape elements, and reclamation of natural areas, are all recipes from the cookbook of agricultural engineering that can be rolled out everywhere and have the tendency to equalize differences. Although convincing new landscapes have been made, the overall conclusion must be that the programmatic drive (reconstruction, housing, and agricultural modernization) dominated over the genius of the place. In extension of this period, one can even say that the emancipation of Dutch landscape architecture in the 1980s and 1990s is linked to the widening of the working field by repeatedly discovering new ‘programs’ that could be turned into landscape (elements).

This golden age of the malleability of the landscape deluded designers into the distorted view that landscape architecture is just the mediation between the program and the place and articulation of the result in spatial terms. We wrote landscape architecture with a capital ‘A’ and tended to overlook the other agents of change: autonomous social and natural processes. The myriad of spatial investments and disinvestments by individuals and other actors gradually change the landscape. The even more powerful effects of natural processes such as succession, weathering, sedimentation, erosion, soil subsidence, and human-induced climate change are agents of change that steer the course of landscape development.

Expand Image

Expand Image