September 9, 2016

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

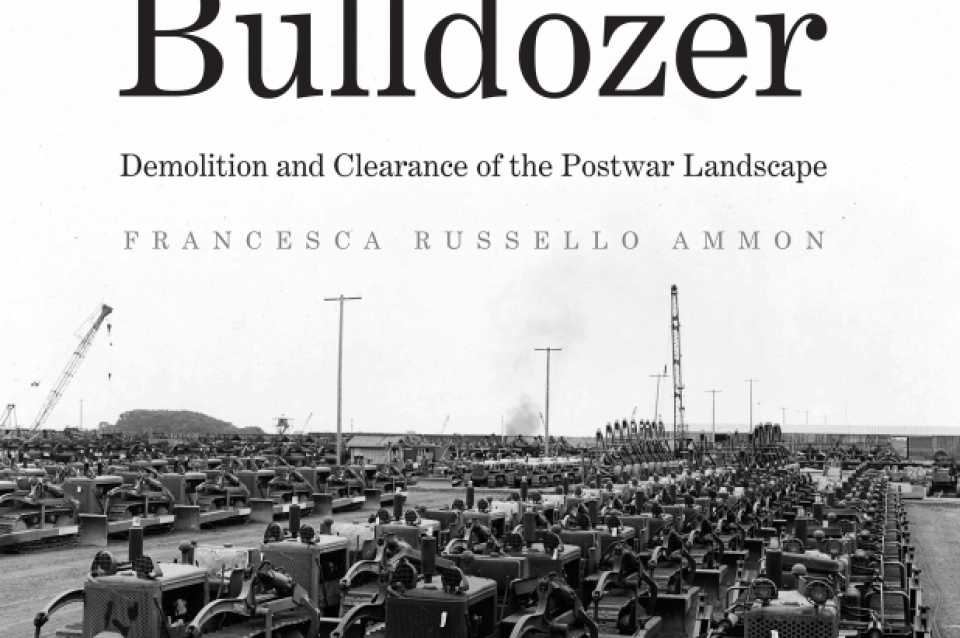

Although the decades following World War II stand out as an era of rapid growth and construction in the United States, those years were equally significant for large-scale destruction. Francesca Russello Ammon's Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016) explores how postwar America came to equate this destruction with progress, and how the bulldozer functioned as both the means and the metaphor for this work. Ammon is Assistant Professor of City and Regional Planning at PennDesign. Following is an excerpt (pages 21 - 24). Ammon is giving a talk on the book on Wednesday, September 14 at the Penn Bookstore, 3601 Walnut Street.

In 1944, Colonel K. S. Andersson of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers penned “The Bulldozer—An Appreciation.” The essay was an ode to a piece of technology then proving critical to Allied success in World War II. “Of all the weapons of war,” he wrote, “the bulldozer stands first. Airplanes and tanks may be more romantic, appeal more to the public imagination, but the Army’s advance depends on the unromantic, unsung hero who drives the ‘cat.’” That same year, a Chicago Tribune writer predicted, “When the axis powers are defeated and the time comes for distributing credit for the allied victory everywhere that it is due, an appreciable share should go to a machine that is constructed fundamentally to take no direct part in the fighting. This machine, tho not designed to play the role of weapon, bears the belligerent name of bulldozer.” Major General Eugene Reybold, chief of the army Engineers, added, “Victory seems to favor the side with the greater ability to move dirt.” An advertisement for International Harvester, one of the manufacturers of these machines, took his assertion a step farther, proclaiming the entire conflict “a dirt moving war.” As Reybold later concluded, “By the war’s end, it was evident that American construction capacity was the one factor of American strength which our enemies consistently underestimated . . . [the one] for which they had no basis for comparison. They had seen nothing like it."(1)

While military construction men, equipment makers, and boosterish wartime journalists were not unbiased witnesses, battlefront evidence corroborates their accolades of the bulldozer. During its first six months engaged in World War II, the Corps of Engineers moved nearly half a billion cubic yards of earth. This exceeded the volume handled in digging the entire Panama Canal. Little wonder that Douglas MacArthur, supreme allied commander of the South West Pacific Area and general of the army, labeled the clash “an Engineer’s war.” In addition, over the length of the entire war, the Engineers’ Naval counterparts, the Seabees, cleared land and built structures for more than 400 bases, 100 air strips, 235,000 roads, 700 acres of warehouses, housing for 1.5 million men, and storage tanks for 100 million gallons of gasoline. The contributions of these men and machines extended beyond construction alone. They cleared bomb-damaged cities of rubble, rescued landing craft that were tossed at sea, and even directly unleashed their power upon the enemy.(2)

Scholars have typically viewed the war as an interruption to the housing and highway work of the construction trades, but in fact the industry participated vitally in the conflict. During World War II an army of construction workers, including 325,000 Seabees, rehearsed large-scale land clearance practices on foreign terrain. When these men returned home, they brought their new and refined skills with them. Their war work also elevated the cultural standing of bulldozer operators and their equipment. Contrary to Andersson’s characterization of the “unsung” Caterpillar driver, diverse media—including trade journals, popular journalism, novels, photographs, and films—publicized his accomplishments. The glorified portrayal of the masculine operator and his patriotic machine rendered them hero and weapon. And the war shaped ideology. Building upon a long history of American environmental conquest, the conflict reinforced a militarized view of the natural and built landscape as enemies to be conquered for new construction. The largely overlooked environmental scars left by the war, coupled with relatively positive representations of urban ruins, made large-scale demolition seem both possible and palatable. Postwar Americans later redeployed wartime machines, methods, and metaphors on the domestic landscape.(3)

Notes

(1)K. S. Andersson, “The Bulldozer--An Appreciation,” The Military Engineer, October 1944, 339; John A. Menaugh, “Bulldozing the Enemy!” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 23, 1944, F2; Reybold on “victory,” quoted in “Tractor Parade,” Time, February 7, 1944, 87; International Harvester Company advertisement, “We’re in a Dirt Moving War!” Construction Methods, March 1944, 161; Reybold on “war’s end,” quoted in H. E. Foreman, Foreword to Van Rensselaer Sill, American Miracle: The Story of War Construction Around the World (New York: Odyssey, 1947), vi.

(2)“Notes and Comment,” Southwest Builder and Contractor, August 14, 1942, 15; Eugene Reybold, “General MacArthur Told Me: ‘This Is Distinctly an Engineer’s War,’” Popular Science, May 1945, 90; “Salute to Seabees,” Los Angeles Times, December 28, 1950, A4; U.S. Bureau of Naval Personnel, The Construction Battalion (Washington, D.C.: U.S. GPO, 1956), 9; William Bradford Huie, “The Navy’s Seabees: They Build the Roads to Victory,” Life, October 9, 1944, 48; Andrew Hamilton, “We’re Back in Business--the Seabees,” Popular Mechanics, May 1951, 111.

(3)“Seabee History: Formation of the Seabees and World War II,” Naval History and Heritage Command Home Page, http://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-… (accessed 5/9/15).

Expand Image

Expand Image