November 30, 2016

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

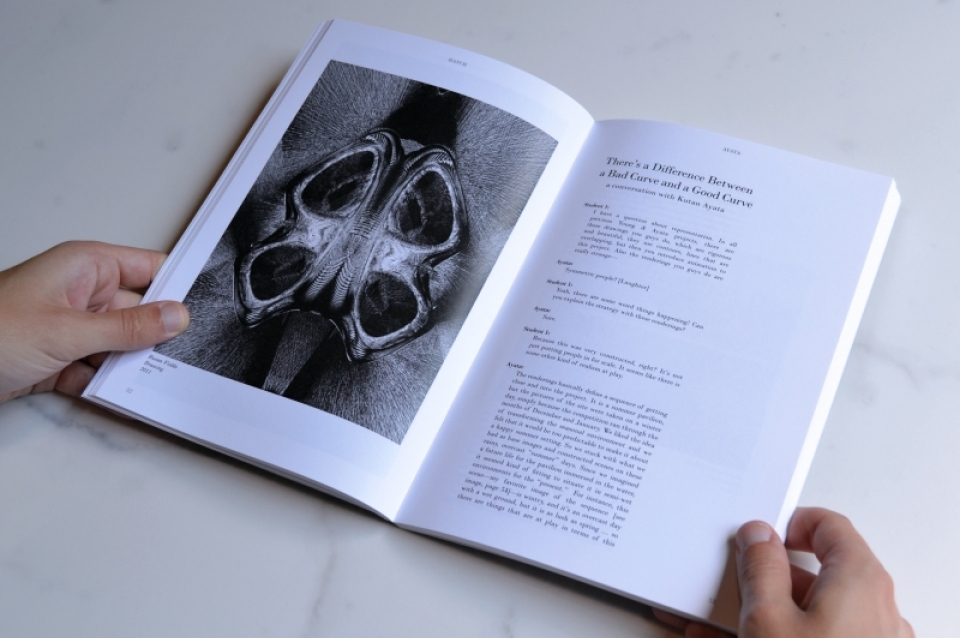

Hatch: On the State of Quick Images is a collection of conversations that took place at PennDesign during the spring of 2015. The conversations were led by a group of students and hosted one or two faculty members. The purpose of the conversations was to interrogate the current status of architectural discourse and the implications of the quick image within that status. Contributing faculty include Kutan Ayata, Josh Freese, Ferda Kolatan, Michael Loverich, Eduardo Rega, Andrew Saunders, and Tom Wiscombe with a foreword by Nate Hume. Below is an excerpt from Kutan Ayata, Founding Partner Young & Ayata.

Student 2: Can you talk about your obsession with, as you say, “crafted curvature?”

Ayata: Do you want to talk about it? [Laughter]

Student 2: Hey, my project for you was all faceted! I don’t know if you remember …

Ayata: Yeah I do … Unforgettable! [Laughter]

This is really a question about our deep belief in craft. I guess this has to do with a reaction towards being able to operate through software platforms, where a lot is dictated through the pre-packaged program definitions, and the desire to develop a level of mannerism as well as a rigorous craft within them … and then really to understand how we control them. I don’t know Maya, like some of these guys know. It drives me a little crazy when you open up a program and there is a box, which you then have to pull and push. I am happy to model a box … but a box as a starting point is kind of weird to me. I like to draw.

Part of it is also has to do with the fact that when I started there were no computers. I started drawing by hand. So I am in this generation where I have seen both sides, and I have to say that I resisted computers for a very long time. I went through grad school without touching much 3D software at all. The only 3D modeling I had done was in AutoCAD, which you can imagine is kind of clumsy and unproductive … but I was always interested in crafting something. I think when mediums shifted for me, and Rhino became the primary tool that we were engaging with, where one could draw and build surfaces simultaneously—draw and model, or model through drawing—it was a natural shift for me coming from hand drawing. I guess the obsession with curvature is to be able to gain the ability to really dictate what specific forms or what specific curvatures suggest and what they do. There is a difference between a bad curve and a good curve. Bad curves can be good for some projects and good curves don’t always work. They might do different things in different circumstances, and both might be necessary in relationship to one another. It’s hard to say what that is … but the obsession is to be able to develop a sensibility in which you can respond to those on a case-by-case basis.

Student 6: Can you talk more about the rendering with the children sitting on the ground and what is symmetric or what is not symmetric?

Ayata: The scene is not symmetric at all. I took the picture in the wrong place, so we just had to adjust to that.

Student 6: Well, I feel like you like symmetry—

Ayata: —But not …

Student 6: Yeah! [Laughter]

Sometimes professors don’t like symmetry and … there is no reason. They just don’t like symmetry!

Ayata: Until we did our Busan Opera House project, I had never done anything symmetrical in my life! I think that was the moment where we began to think about figuration and architectural objects in a different way.

Historically, symmetry is about a central narrative that goes towards the axis, like in the Renaissance, and it always reinforces the singularity of a central axis. Everything goes through that focal point … all the narration … all sense of order and power goes towards that axis. For us, the axis is the way we start to establish global symmetry, and then develop local asymmetries around that axis. So it’s not a narrative driven strategy that’s central towards that focal point, but it’s a non-linear narrative about multiple conditions that grow out of the central axis. The symmetry is a moment for us to pin down any field condition, any non-directional pattern, or any incomplete figure and start to iterate. This allows us to produce figuration in a very efficient way. There have been different things we’ve done with symmetry. We are really trying to explore it in multiple ways. I am not sure if anything will be as purely symmetrical as Busan. That was kind of a first attempt. Everything after that has found ways of challenging that strong symmetry. Even though the thing might appear symmetrical, there are a lot of moments within projects that begin to push on the initial order of the symmetry.

Student 6: When we deal with complex objects, it is really hard to make or give it order.

Ayata: You can’t do symmetry for the sake of symmetry. I don’t think there is a project in that. We call our symmetries “odd symmetries.” Globally, they might appear to be symmetrical, but when you get into it, one begins to experience nuances, which hopefully produce a very different trajectory for one to experience the work. It’s not that one side equates to the other … it is different, but it’s just not apparent. That subtlety is something we are really interested in. Not necessarily subtlety of form—that’s not what I’m suggesting—but subtlety of articulation in the way halves of local symmetries or halves of global symmetries begin to differ.

Student 6: Would the Guggenheim Helsinki Museum be seen that way?

Ayata: Right, it seems symmetrical, but the only thing that is symmetrical there is the moment the columns touch the ground and the moment the skylights end. It’s only in those two moments where the project is absolutely symmetrical. Everything else in between—the geometries and the articulations —are absolutely asymmetrical, but it’s hard to catch because they move in very subtle, weird ways. There are no other moments of perfect symmetry across the axis.

There is absolutely no condition in the world, as in site condition, which would necessitate an architect to say, “This should be symmetrical!” There is absolutely no condition, right? So it automatically allows one to produce a degree of autonomy in the way one conceptualizes the work. There is absolutely no reason to do symmetry … but we, as architects, have been doing it for a few thousand years. It’s our way to say, “Here is this thing that has no relationship to anything else.” So the object withdraws and gains its autonomy. I think that is an incredibly powerful notion.

Expand Image

Expand Image