March 19, 2017

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Areas

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

Since last spring, when North Carolina enacted a law requiring individuals in government buildings to use the bathrooms that correspond to the gender marked on their birth certificates, the state has been subject to boycotts, protests, and even bans on city-funded travel from Philadelphia. But even in Philadelphia, which is widely considered progressive with respect to LGBT issues, the typical public building has a bathroom set aside for men and a bathroom set aside for women.

Gendered bathrooms aren’t a response to inborn human needs, said Joel Sanders, an architect and Yale professor adjunct, in a recent lecture at PennDesign. Instead, they’re an expression of cultural beliefs. And finding new ways to design public accommodations that accommodate transgender and gender-nonconforming people is as much an architectural question as a political one, Sanders said.

Sanders’s talk, titled Non-Compliant Bodies: Social Equity & Public Space, was developed out of research he did with Susan Stryker, a professor of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona. The current debate about trans individuals and public restrooms fits into a longer history of angst about marginalized groups entering mainstream society, such as occurred during the days of segregation, they wrote in an essay published in the South Atlantic Quarterly. Fears about trans people using gendered bathrooms play on “stereotypes of transgender women as sexually perverse men.” And architects are complicit in manifesting the ideas of gender normativity that hold sway in public space.

“Our objective is to shift the terms of the argument, recognizing that safety is one symptom of a larger dilemma posed when groups that mainstream society considers abnormal or deviant clamor for non-prejudicial access to public space,” Sanders and Stryker wrote in the essay, “Stalled: Gender-Neutral Public Bathrooms.”

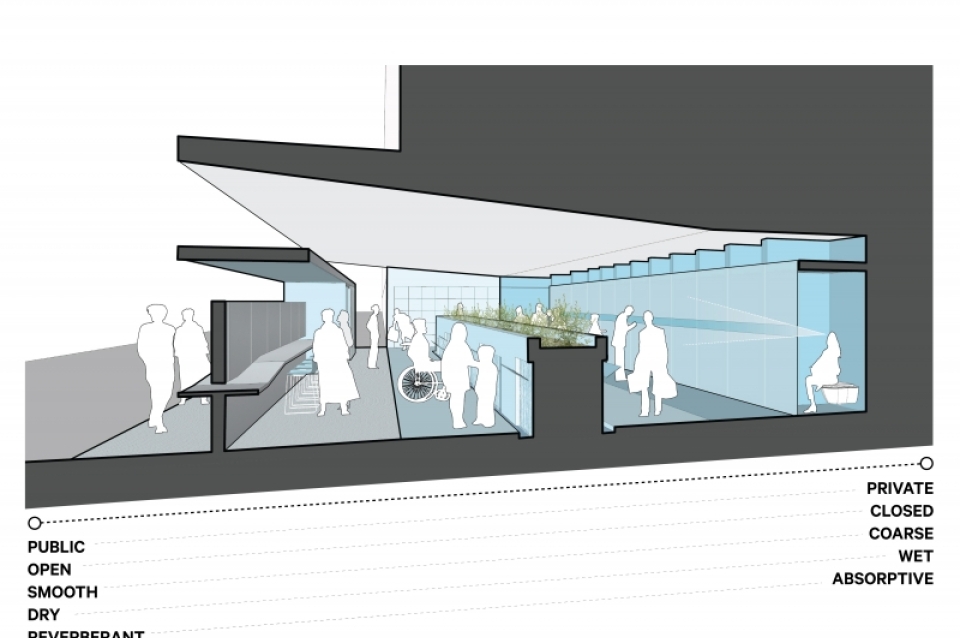

To begin to address the issue, Sanders and his firm are at work on new restroom prototypes that take into account not just gender diversity but all the various ways in which a public restroom is and could be used. One prototype, meant for a large public facility like an airport or train station, is split into three areas by activity: washing, coifing, and eliminating. Bathroom stalls have floor-to-ceiling walls that guarantee privacy, while the washing areas are common and designed to work for people of various heights and dis/abilities. Overall, the spaces are designed to keep users safe by encouraging strength in numbers, the proverbial eyes on the street.

“Bathrooms are, I hope I’ve convinced you, sites of social exchange—charged spaces where social, psychological, technological, and ecological forces converge,” Sanders said at the conclusion of his presentation. “And like other spaces attuned to cater to the needs of the biological body, we take these spaces for granted. But their design, their configuration, their choice of materials, both allows and disallows different kinds of bodies to perform their identities differently in public spaces and private ones.”

“Architects and designers must step up to the plate and explore the design consequences of these urgent social justice issues ... In the process of discovering these creative solutions, we’re not only going to match the particular user needs of noncompliant bodies, but what’s really important, what’s at stake, is changing social awareness. The creation of accessible spaces that foster mixing will, in the end, breed tolerance and respect for human dignity and human difference.”

Expand Image

Expand Image