May 7, 2016

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

Part 1 of a two-part Q&A with Chris Marcinkoski, Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture, partner/director at PORT, and a Rome Prize Fellow at the American Academy in Rome (AAR).

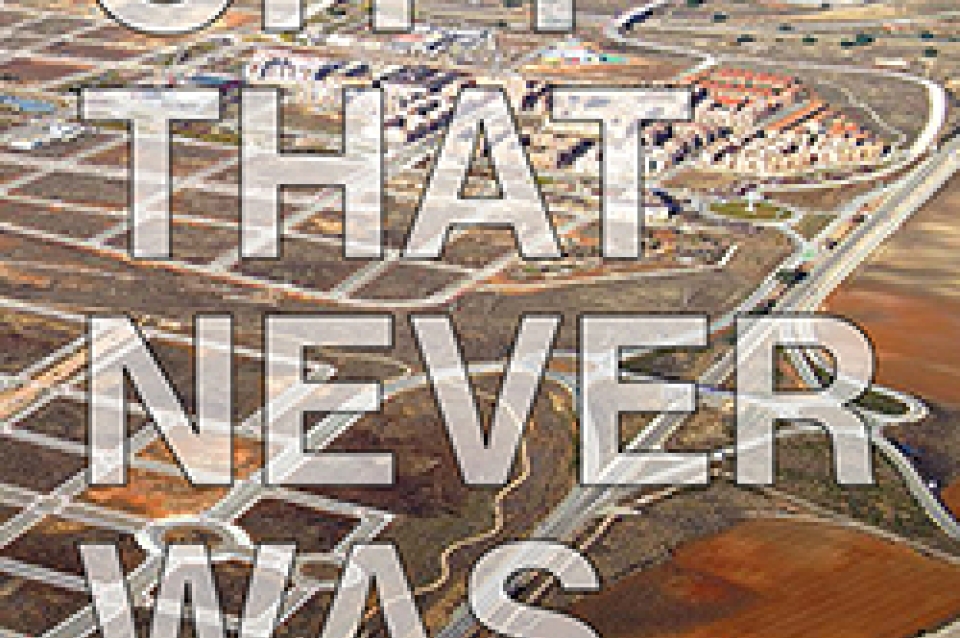

PennDesign: With your new book, The City That Never Was, you seem to carve out a productive new space for research and dialogue at the intersection of design and economics. Was this a conscious goal?

CM: It wasn’t a conscious goal when I started the research focusing on Spain’s recent urbanization boom and bust, but as I began looking at other examples of speculative bubbles, it became very clear that there was a relationship between urban design and economics that was superficially acknowledged, but rarely engaged—either in theory or practice. Once one realizes how central speculative building has become to the global economy, it seems absurd that the urban design disciplines aren’t more fully engaged in the motivations that drive this type of urbanization, as well as in trying to assuage its myriad consequences.

PennDesign: How does the work you’re doing at the AAR this spring build on the book?

CM: In the first chapter of the book I discuss a number of antecedent and ongoing examples of speculative urbanization. One of the current examples I touch upon are the so-called African New Towns that began appearing at the height of the prior boom period—around 2005-2006—and have continued to be pursued right through the recent period of economic unrest to today.

What is interesting about these proposals for new settlement and infrastructure is that despite the urgent demand for urbanistic upgrades throughout much of the continent, the numerous proposals that characterize recent urbanization activities are rarely oriented toward those populations or urban landscapes actually in need. Rather, exogenous models are being imported into wholly incongruous environments with little regard for the realities of their destination. In essence, Africa is in the process replicating many of the recent mistakes made in places like Spain, Ireland, Dubai and China by subscribing to the very same urban growth models that set these polities up for their recent—and possibly forthcoming—urbanistic and economic failures.

The work I am undertaking at the AAR is the beginnings of a follow-up book project to TCTNW. The project is structured into two parts: 1) A critical survey of territorial-scale speculative urbanization projects proposed or undertaken throughout Africa since 2005; and 2) the elaboration of potential alternate futures for these projects by means of adjustment to the planning, design and construction conventions upon which they rely.

PennDesign: How does your study of speculative urbanization inform your practice?

CM: Up to now, I have intentionally kept the academic research separate from the professional practice. That said, it is difficult to not be suspicious of certain large-scale urbanization initiatives when one has spent four-plus years thinking about how often and dramatically these kinds of projects fail due to their inherent optimism bias.

The big takeaway for me, and this gets translated into the planning and design work of the practice, is that to focus solely on the preferred outcome of a project is setting it up for failure. There are far too many variables to account for when it comes to a long-term urban transformation.

So our interest is less in producing a singular, desired solution or outcome, than in elaborating a framework for transformation—both physical and procedural—that can be adjusted and modified over the extended timescale of a particular project’s implementation and occupation.

PennDesign: Your firm has adopted a hybrid model, bridging urban design, architecture, landscape architecture, ecology and urban planning, that seems to be increasingly appealing to both practitioners and clients. Is it a matter of competitiveness in pursuing certain kinds of projects, or are projects just more complex than they used to be?

CM: Well, we like to think the hybrid model should be more appealing to clients, but that is not always the case! I think our particular practice model has evolved alongside our interests as much as in response to the demands of contemporary project types.

For us, thinking about the city or a particular urban condition inherently demands a range of approaches. We certainly enjoy collaborating with experts in particular disciplines, but we also like to have a broad range of expertise and points of view in house. From our perspective, the sooner the field of operation is expanded beyond a singular disciplinary interest, the sooner a wider range of opportunities for potential action come into focus.

At the end of the day, I don’t think urban design projects today are necessarily any more complex than they were previously. Rather, the expectations now are greater in that urban designers and planners must actively engage and negotiate the totality of these myriad complexities rather than simply trying to control them or design them away as in the past.

Expand Image

Expand Image