Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Robert Venturi (June 25, 1925 - September 18, 2018) joined the faculty at Weitzman School in 1957. It was at a faculty meeting, in 1960, when the future of Frank Furness’s Fisher Fine Arts Library was hotly debated, that he met his future wife and business partner, Weitzman School alumna Denise Scott Brown (MCP’60 and MArch’65).

Teaching at Weitzman School was a defining episode in Venturi’s long career, and he left an indelible impression on hundreds of students before deciding to dedicate himself to his practice in 1965. From 1961 to 1965, he taught Theories of Architecture, one of a series of groundbreaking theory courses offered at the time whose energizing influence can be seen in projects such as Grand’s Restaurant, New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, Guild House, the North Penn Visiting Nurses’ Association, and particularly the Vanna Venturi House. As Venturi himself related, his legendary 1966 book Complexity and Contradiction grew directly out of his Architecture 511 course.

Venturi’s close relationship with Weitzman School continued to evolve over the course of his life. From 1985 to 2002, he served on the Board of Overseers. In the late 1980s, the firm he led with Denise Scott Brown was engaged to lead the restoration of the Fine Arts Library; work was completed in 1991. Says William Whitaker, curator and collections manager at the Architectural Archives, “We here at Weitzman School love the Furness building, and Bob and Denise helped us learn to love it again.”

In 1998, the firm began working with the Archives to establish the Venturi, Scott Brown Collection. In the subsequent two decades, they transferred drawings, models, photography, and correspondence papers to the Archives, creating the most extensive documentation of their architectural and planning projects to be found anywhere in the world.

Here, a selection of individuals who studied or worked with Venturi, as well as leading scholars on his work, reflect on his many contributions. To add your voice, contact news@design.upenn.edu.

David B. Brownlee

Frances Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Professor of the History of Art, Penn

Robert Venturi treated people with gentleness, ideas with ferocious intelligence, and architecture with fertile imagination. Like all truly great architects, he was more than an architect. Indeed, he invented the vocabulary with which we discuss all of late twentieth-century culture. It is “complex and contradictory,” he wrote, and it challenges us to “learn from Las Vegas” and from just about everything else. But while envisioning an architecture “based on the richness and ambiguity of modern experience,” Venturi demanded that it be more than a collage of disparate elements. Architecture, he asserted, must strive for wholeness; it “must embody the difficult unity of inclusion rather than the easy unity of exclusion.” At a moment when exclusionary rhetoric echoes through the public sphere, we should heed the challenge in those words and draw inspiration from the simple seeming buildings that Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown devised to meet our complicated needs.

David G. De Long

Professor Emeritus of Architecture, Weitzman School

Robert Venturi, together with Denise Scott Brown, changed the course of architecture, as now widely acknowledged. But their influence extends further. For through their pursuits they enhanced our experience of material culture, resulting in a new, more sympathetic understanding. Bob’s kind and gentle nature, and his remarkable generosity (especially toward students, as I experienced at Penn many years ago) add immeasurably to these achievements.

Winka Dubbeldam

Miller Professor and Chair of Architecture, Weitzman School; founder and partner, Archi-Tectonics

Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction, published over 50 years ago now, was, and is, a groundbreaking architectural publication. For me, it was the book that started my interest in philosophy and critical thinking (theory) in architecture. Venturi was such an important thinker and architect, and his work and books influenced so many people in their careers. I feel very lucky to have met Bob and Denise early in my career at Penn, when, as a young faculty member, I was asked by then dean Gary Hack to present my students’ work to the Board of Overseers. When I arrived for the meeting, I was excited and nervous to discover that Bob and Denise both were on the Board. But they were excited to see the work, and we had a great conversation after the presentation. Our thoughts and warm wishes are with Denise.

Robert Geddes

Former faculty member, Department of Architecture, Weitzman School; Co-founder, Geddes Brecher Qualls Cunningham: Architects

Bob and I collaborated in teaching design studios at Penn for several years. In many meetings, the School's faculty held likely conversations about architecture and urbanism. How do I remember Bob Venturi? With profound admiration.

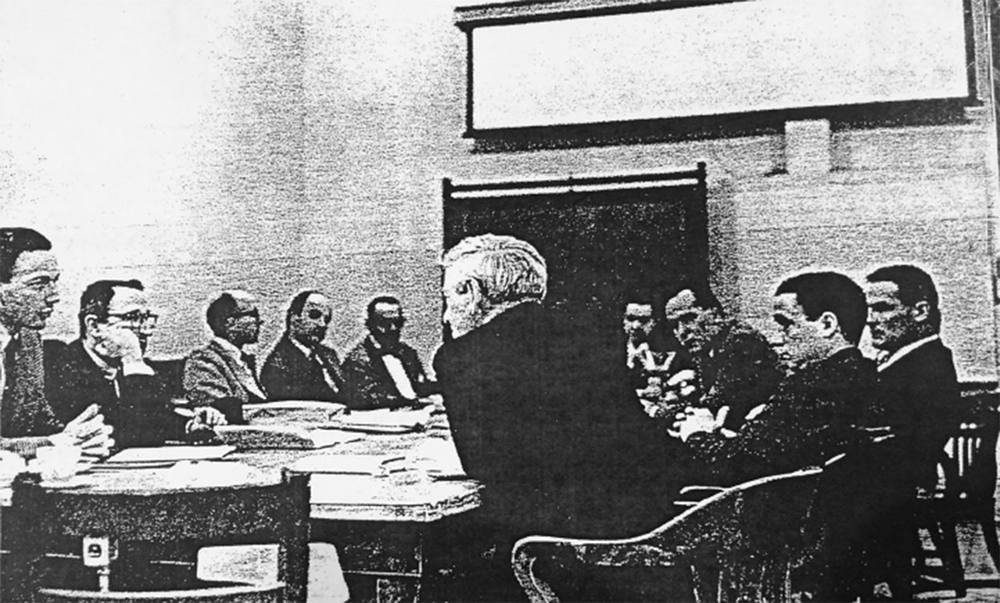

Architecture faculty at University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Design (now Weitzman School), c. 1961. Pictured (left to right): Tim Vreeland, Robert Geddes, Leon Loeschetter, Romaldo Giurgola, William Wheaton, Louis Kahn, Unidentified, G. Holmes Perkins, Robert Venturi, Thomas Godfr.

Steven M. Goldberg (MArch’65)

I was blessed to be Bob’s student and have him as my studio critic for three of the six semesters of graduate school at Penn. The knowledge he imparted greatly influenced my work for the next 50 years. Here are just two examples of his gifts as a teacher.

“Upon starting a project immerse yourself in the details of its program, site, culture and historic precedents,” he said while sitting next to me at my desk. “Then forget everything and start to design!”

During one of my thesis crits I told Bob that I had received a Chandler Travel Grant and would appreciate his help in planning the trip. He was emphatic that I should be based in Rome and branch out from there. We spent the rest of the day devising the itinerary. He went over his favorite cities and buildings in Europe and the Middle East. I took detailed notes filling 85 pages of a 4” x 7” notebook (which now resides in the Penn Architectural Archives). I would never forget his advice on tackling Venice: “Get lost.”

Stephen Kieran (MArch’76)

Associated faculty member, Department of Architecture, Weitzman School, and alumnus; Partner, KieranTimberlake

My education as an architect only really began watching Robert Venturi at work. On a weekend, with an opera on the radio as background, he would work his way into a project. Layer upon layer of yellow trace flowed, one atop another, as the ideas built, then disintegrated, only to give rise to yet another beginning. Eventually, we would be drawn into the endless rounds of iteration and discovery with him. This is how he taught myself and countless others, the hard and wondrous work of a lifetime spent becoming an architect. He was a maestro in every sense of the word, orchestrating his complex and contradictory world view one work at a time. His was not an easy world, but it was a powerfully moving one. As a young student coming of age through the 1970’s, there was not much that we were not against. He showed us a way forward to something we could be for, a world of judgement and nuance, neither black nor white, just endless shades of ethical grey that required work, not simple dogma. This is where his moral compass and creativity resided. His was a world as layered as his sheets of yellow trace, one that included rather than excluded. The past was layered forward into the present, the present flowed backwards into the past. Acceptance and retention trumped exclusion and demolition. His presence is already missed.

David Leatherbarrow

Professor of Architecture, Weitzman School

The “Gentle Manifesto” announced half a century ago in Complexity and Contradiction proved to be anything but mild or moderate. The buildings that followed radically reorganized their locations, as well as our conceptions of how late modern cities could be reshaped, and his writings and lectures corrected the compass of architectural theory, especially conceptions of the ways buildings, landscapes, and cities communicate the culture they accommodate. Though he expressed profoundly humane tenderness when offstage, when in public and at work the man, too, was anything but gentle: strong in his convictions, irreverent, exploratory, and playful. When sitting next to him at a lecture one night, I was amazed at how prolifically and pleasurably he doodled. Apart from the populist ethos and dedication to vernacular culture, Robert Venturi was from beginning to end an architect’s architect whose love of the discipline led him to repudiate then redefine its norms.

Joan Ockman

Senior Lecturer, Department of Architecture, Weitzman School

Robert Venturi’s contribution to the architectural culture of the last third of the twentieth century was original and profound. Equally a thinker and a maker, his early books Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) and Learning from Las Vegas (1972, with Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour) were instrumental in articulating the set of ideas that would soon be coined as postmodernism. Projects like the Vanna Venturi House and Guild House translated his theories into built form. While other architects recognized the failures of late modernism by the 1960s, Venturi was among the first to produce a body of work that launched architecture in a genuinely new direction.

Patrick J. Quinn (MArch’59)

Institute Professor Emeritus and former dean, School of Architecture, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute; Alumnus

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown transformed the way some of us think about architectural, design, history, and theory. Their delightfully subtle sense of humor knocked the feet out from under the puritanical attitudes held by those who valued orderliness over order—“order” not in the sense of rules and regulations that can stifle true creativity, but in the sense of Lou Kahn’s idea of “existence will,” something that combines the infinite possibilities of poetics with the hard-nosed practicality of what makes people happy with the real world. Kindness, above all else, was the fundamental quality that, for me, makes Bob and Denise so profoundly important in my life and the lives of thousands.

Frederick Steiner (MRP’77, MA’86, PhD’86)

Dean and Paley Professor, and alumnus, Weitzman School

Bob Venturi changed fundamentally the course of architecture theory and practice. Like the city of Rome that he loved so much, Bob’s work captures that sense of the eternal that spurs creativity and imagination for generations to come.

James Timberlake (MArch'77)

Associated faculty member, Department of Architecture, Weitzman School, and alumnus; Partner, KieranTimberlake

At Penn in the Fall of 1974, ‘all in’ on Louis Kahn, who died the day I received my acceptance to graduate school, I wondered what ‘was next’ architecturally and philosophically? That fall, challenged as to whether I had read ‘Robert Venturi’, read Complexity & Contradiction, I took that challenge and came to appreciate something truly different in the world of architectural history and theory. The book captivated me, and still does. I’ve re-read the book 7 or 8 times. My copy is dog-eared and annotated from travel having visited many of the references.

Upon graduation, working closely with Bob at Venturi & Rauch, then Venturi, Rauch & Scott Brown, was intense, always toward an unknown perfection: a holy grail pursued by countless hours, missed holidays, and endless changes toward the next architectural opportunity–a sketch, drawing, model or revision to a plan or elevation, none never necessarily presented immediately, readily, or in the moment. For a young architect sharing those philosophies ‘of the work’, as it might be defined, it was heaven. Saturdays and Sundays in an empty shop, with NPR’s opera blasting loudly, whether at 16th & Pine or in Manayunk, drawing, perfecting, changing, drawing again nearer toward perfection, was bliss, heaven, nirvana.

My heartfelt gratitude, Bob, for that opportunity. I’ve yet again taken out my copy of C&C, and am reading it, in your memory.

Thank you.

Terry (C’66) and David Vaughn (C’66, MArch’68)

Alumna and retired adjunct associate professor of architecture, Weitzman School; alumnus and retired principal, Venturi Scott Brown and Associates

It was September of 1963 when we entered the great old studio on the second floor of Hayden Hall and first learned of the already legendary Bob Venturi through the student grapevine and the graffiti on the studio walls. It was a heady time, the flowering of a transformation in architectural thinking, and Bob Venturi was at its forefront. His studio critiques, sometimes surprising, always revealing, occasionally accompanied by a wry smile, and his quirky, brilliant theory course brought the investigation and understanding of architecture to an entirely new level for us. Exploring buildings a-historically through the elements of architecture gave us new ways of thinking about design in our studio work.

When we went on to work for Venturi and Rauch, we found his office to be an extension of the studio, Bob thinking out loud at our desks, making the design process visible with his incomparable hand, continually directed and redirected by his deep understanding of architectural history and construction.

Over the years, much emphasis has been placed on the decoration and historical reference in Bob’s work, but from studying and working with Bob during those early years we take with us his lessons in the larger questions of architecture: those of contextualism in time and place, space and human scale, mastery of plan and section making, response to human need, and how these are realized through the thoughtful making of buildings.

He lived the seamlessness between theory and practice.

Select Obituaries

Fred A. Bernstein, The New York Times

“Though he disowned the title, Mr. Venturi was often called the father of postmodernism. Philip Johnson, who left his own large imprint on 20th-century architecture, said in a conversation with the architect and author Robert A. M. Stern in 1985 that Mr. Venturi’s ‘Complexity and Contradiction’ had helped liberate him from modernism’s rigidity.”

Inga Saffron, Philadelphia Inquirer

“Philadelphia, a city that is both innovative and resistant to change, is probably the only place in America that could have produced a figure like Mr. Venturi. His work combined the best aspects of his hometown to open up the world to a new way of seeing buildings.”

Aaron Betsky, Architect

“Venturi was trying to save Modernism from its own pronouncements more than from its practices. To a large extent, he won, to the point now that we cannot think of architecture since 1966 without reference to Robert Venturi.”

Ashley Hahn (MCP/MSHP’08), PlanPhilly and WHYY

“Like Louis Kahn before him, Robert Venturi is one of the great architects Philadelphia has shared with the world. And some of his most important work is local. One of Venturi’s most significant works has been called one of the most influential buildings of the 20th century: The Vanna Venturi House (1964) in Chestnut Hill was designed for his mother, and launched him into early, albeit controversial fame.”

Ned Cramer, Architect

“Venturi’s rebellion freed architects to pursue interests that not only diverged from the modernist canon, but from his own semiotic approach as well. The post-Euclidean geometries of Frank Gehry, FAIA, and Zaha Hadid, for instance, exhibit little obvious relation to the studied mannerism of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates (VSBA), but the debt exists nonetheless.”

Expand Image

Expand Image