May 23, 2024

Across Weitzman, Studios Set Out to Improve the Quality of Life in Philly

By Jared Brey

Hilary Li's proposal for an arts venue and housing development in Philadelphia's Market East neighborhood

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Hilary Li's proposal for an arts venue and housing development in Philadelphia's Market East neighborhood

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

Every year, Weitzman studios take students all over the globe, from remote landscapes to bustling world capitals, to learn from local residents and partner with overseas institutions. During the last academic year, students in every discipline also explored sites in their own backyard, tackling affordable housing, heritage conservation, traffic congestion, equitable development, and other challenges faced by Philadelphians today.

In addition to the sampling here, there's more work from 2023-2024 studios to explore in the virtual gallery of the Weitzman Year End Show.

In Philadelphia's West Poplar neighborhood, where a lack of density and outdoor space reflect chronic disinvestment, Devon Bruzzone and Annie Parker propose a new pedestrian corridor to encourage intergenerational exchange and increase accessibility.

Investing East of Broad

The quadrant of Center City east of Broad Street and north of Chestnut is marked by tears in the urban fabric: sunken highways, surface parking lots, Independence Mall, the Pennsylvania Convention Center, and the Reading Viaduct, to name a few. Envisioning new large-scale development in that space was the charge given to students in Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture Christopher Marcinkoski’s urban design studio this spring.

The urban design studio, which Marcinkoski has been leading for a decade, is focused on making investments in the public realm that can “organize equitable development,” he said at the final review in May. Students selected sites of around 20 acres each, and were tasked with designing cohesive urban improvements, including public parks, civic facilities, mixed-use commercial development, and housing.

In West Poplar, Master of Landscape Architecture students Devon Bruzzone and Annie Parker envisioned new community space as part of a low-income public housing development. Their site, on Melon Street near Spring Garden Elementary School, sits near the former Richard Allen Homes, a predominantly Black public-housing community dating back to the 1940s which was redeveloped in the early 2000s, resulting in a much smaller neighborhood population. The project involves a reinvigorated Philadelphia Housing Authority reclaiming its role as public developer. Bruzzone and Parker sought to densify public housing in the area without repeating the social isolation of the early era of public-housing project towers, planning a pedestrian corridor on Melon Street, the mixed-use activation of a nearby food warehouse, and a new public library and gym at Spring Garden Elementary. The project is built on the notion of housing as a human right, the students said, and “development as racial reparations.”

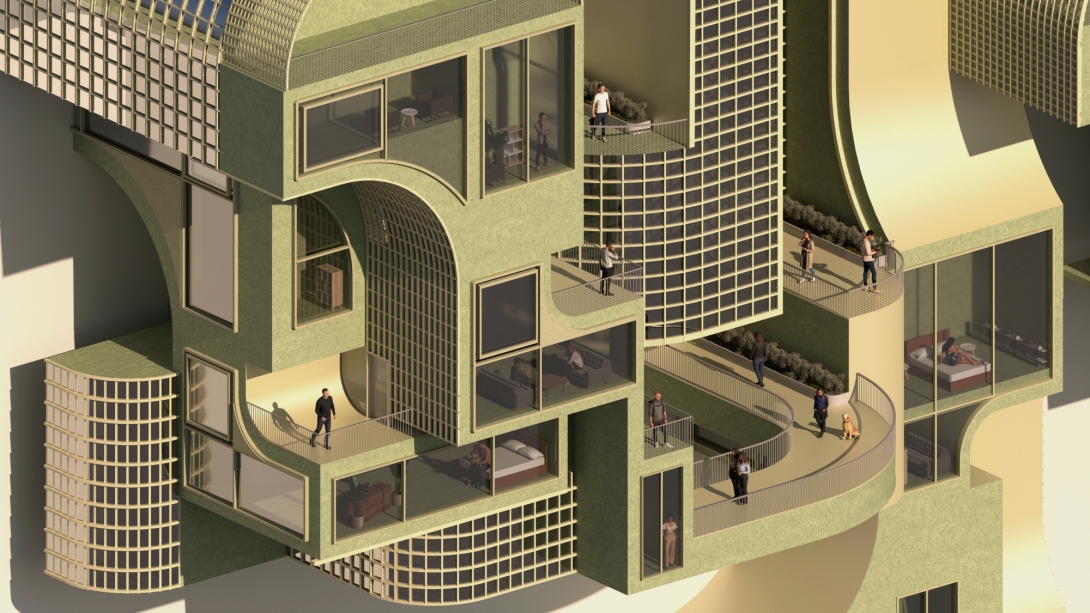

The Pyramid Club at 1517 W. Girard Avenue in the early 1940s (Photograph by John Mosley, Blockson Afro-American Collection, Temple University Library)

Commemorating Philadelphia’s Black Heritage

Black people have lived in Philadelphia since before its founding in the 1680s, and today the city has one of the biggest populations of Black residents anywhere in the U.S. Despite that, Philadelphia’s Black heritage in the built environment is poorly documented and not well protected, says Amber Wiley, Presidential Associate Professor of Historic Preservation and director of the Center for the Preservation of Civil Rights Sites. This spring, in a seminar called Revolutionary Approaches to Philadelphia’s Black Heritage, Wiley asked students to investigate and document significant episodes in the Black history of the city—and find creative ways of commemorating them.

The course began with a mapping exercise to track the growth and movement of Philadelphia’s Black population over time. Students tended to zoom in on episodes and movements in the 19th and 20th centuries. One student, Yuexin Liu, explored the footprint of the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia, while another, Laurie Wexler, documented sites associated with the Green Book, a travel guide for African Americans in segregated midcentury spaces.

Robert Killins focused on the role of civic organizations in “cultivating the Black community into what it is today,” documenting spaces like the Pyramid Club, a former social club for the Black middle class at 1517 Girard Avenue in North Philadelphia. Killins created a trailer for a hypothetical documentary entitled It Takes a Village that would illuminate the history of those organizations.

Like Killins, most students leaned into the public-history aspect of the course and chose commemorative methods that were a departure from the nomination of buildings to the local historic register that is the bread-and-butter of historic preservation work. It was a way of “flexing their creative muscle,” Wiley says. Still, she was sure to emphasize that the projects needed to identify specific properties that reflected the periods of significance the students explored—a recognition that Philadelphia’s Black history is built into the cityscape itself.

“There is a three-dimensional quality to a home or a site that you can feel as you walk across the threshold,” she says. “You understand as an embodied experience that someone lived here: Someone very important, but also someone like me.”

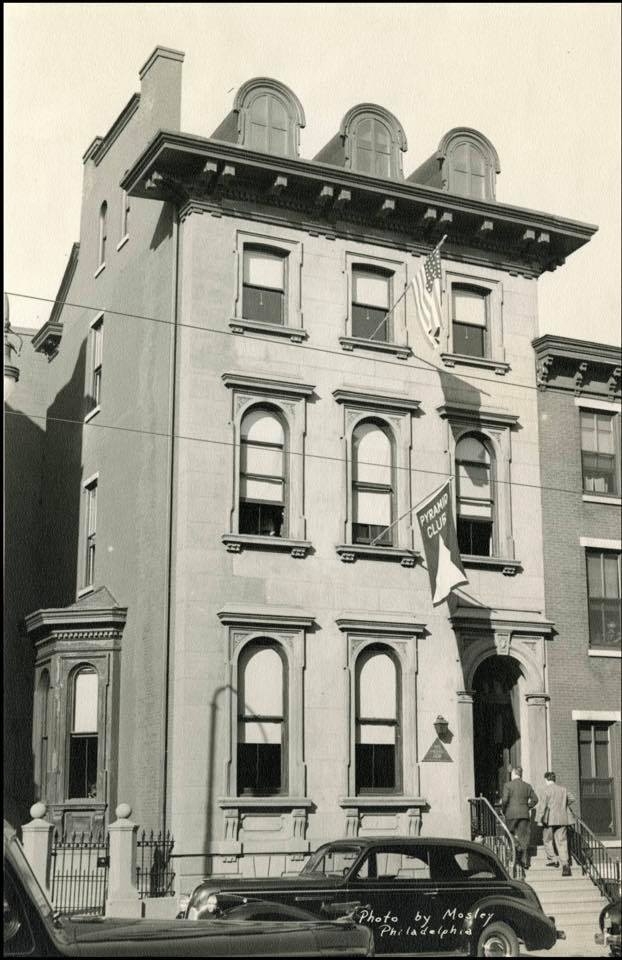

Fiona Rath's design for a housing development in Market East

Welcoming Immigrants to Market East

Market Street east of City Hall has been a transitional space for generations of Philadelphians, often subject to big dreams of transformation but never quite taking on a sustained momentum of its own. Last fall, in an architecture studio led by Lecturer in Architecture Brian Phillips, the founding principal of ISA, students worked to envision the space as a gateway for new immigrant communities.

They were tasked with designing new large-scale development within and above the existing Fashion District, formerly known as The Gallery, on the north side of Market Street between 10th and 11th. The projects needed to include housing and supportive programming for new residents. Students were also told to be thoughtful about the “public commons” aspect of the development, including the ways in which the commercial and residential developments interact with the adjacent train station and public sidewalks—long considered a weakness of the Gallery project. They worked with the Welcoming Center, a nonprofit that works with immigrant communities, to hone the concept.

Students took creative approaches to the design, anchoring new housing with spaces meant for music and public performance, food cultivation and distribution, or daycare for children. With opinion sharply over a current proposal to build a new arena for the Philadelphia 76ers at the site, some teams sought to use their design to expand Chinatown’s cultural footprint, rather than further hem it in.

This spring, Phillips organized a panel discussion with the Design Advocacy Group, which focused on the layered history of Market East and the diverse communities that have a claim on it. Planners have long envisioned the site as a magnet to draw people—specifically the white middle-class—from the suburbs. But Philadelphia’s growth over the last decade has been led almost entirely by immigrants. What if our marquee urban spaces were built for them instead?

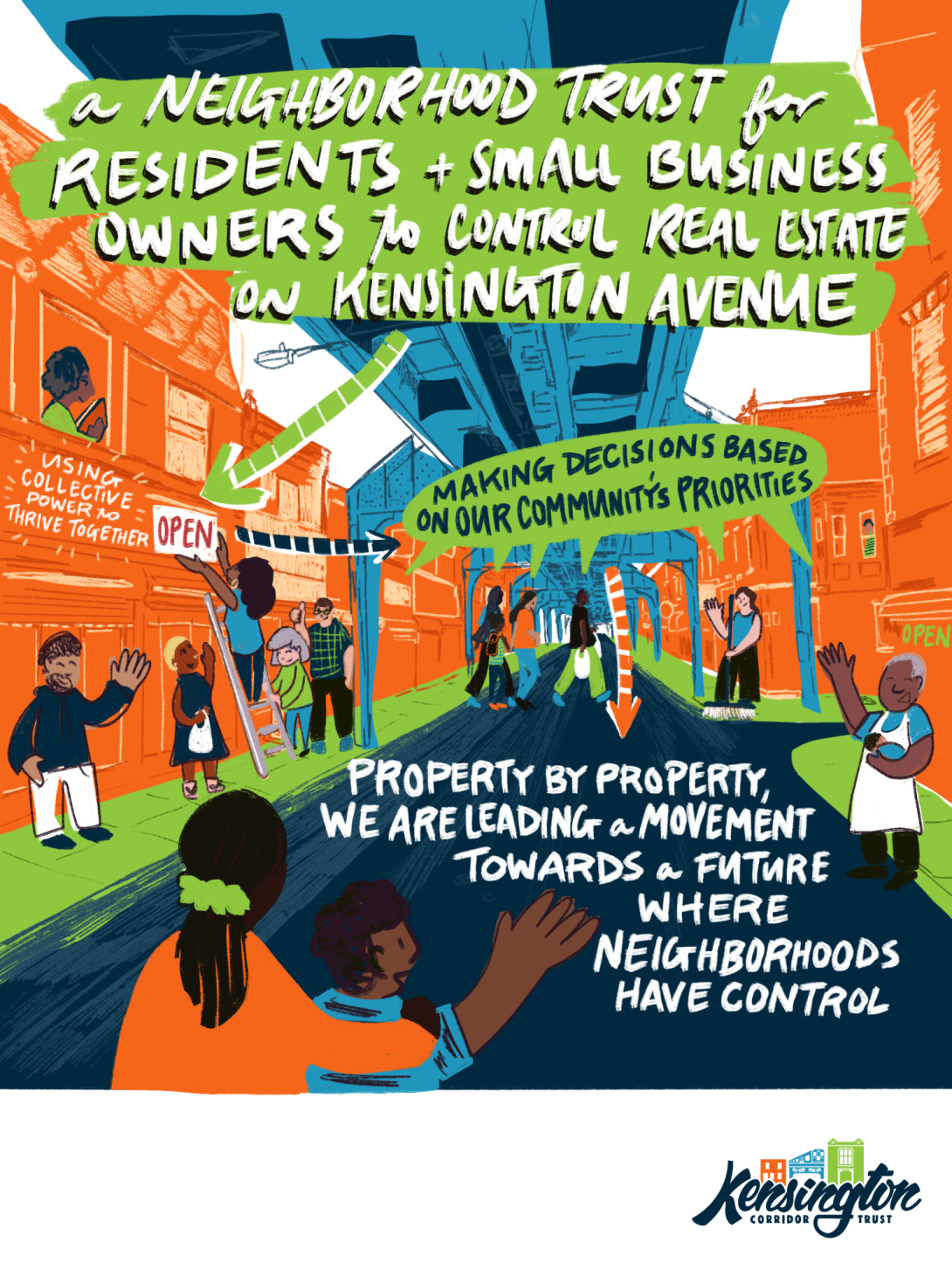

Kensington Corridor Trust's illustrated explainer of its mission (KCT Document Center)

Environmental Justice in Kensington

Kensington Corridor Trust is a nonprofit community development group that owns commercial property on Kensington Avenue in one of the most challenged neighborhoods in Philadelphia. For the third year in a row, the Trust has partnered with Weitzman Master of City Planning students to strategize on cleaning and greening initiatives for the Kensington Avenue corridor. The partnership is organized through a housing, community and economic development practicum led by Kevin and Erica Penn Presidential Professor Lisa Servon.

This year, students focused on the legacy of environmental injustice in Kensington — the accumulated effects of industrial activity, pollution, short dumping, truck traffic, and a lack of street trees and green infrastructure. At the Trust’s request, students investigated the viability of various small property-level interventions, like microgrids, waterhogs, green roofs and solar panels.

“Some of it is remediation of the existing buildings,” Servon says, “where they can do things that don’t seem so heroic but have a payoff.”

Working in two teams, students developed a prioritized matrix of potential interventions, detailing the resources available for them, and the tradeoffs in terms of costs and benefits. They compiled the proposals in a PowerPoint presentation—something the Trust asked for, which it uses to help visualize a narrative around its work and fundraise for projects.

“I always want us to be producing work that’s important and useful to our partners,” says Servon, who’s taking sabbatical for the next academic year but plans to continue working with Kensington Corridor Trust in future semesters. “From a perspective of integrity it’s the right thing to do if you can keep working with a partner and make that relationship stronger instead of just hopping from place to place … The benefits start to accrue to an organization when we go back over and over again.”

Smart Loading in Center City

Center City’s tight streets and abundant restaurant and retail environment are part of its draw. But they create headaches for delivery drivers and downtown visitors who help keep the neighborhood working. When drivers resort to double parking or blocking crosswalks, they can cause traffic congestion and unsafe pedestrian conditions and interfere with transit service. This spring, students in the Master of Urban Spatial Analytics program worked with Philadelphia’s Office of Information Technology and Innovation Management Team to study how “smart” loading zones could help keep things flowing downtown.

The city ran a pilot program using smart loading zones last year, allowing drivers to reserve time in select spots in the core of Center City. Officials shared data from that pilot with students in the Smart Cities Practicum led by Associate Professor of Practice in City and Regional Planning Michael Fichman. Students quickly identified a series of limitations in the data: The pilot program was short-lived, confined to a small geographic area, and had limited uptake among users. But they developed a program, Smart Loading Zones, that could accurately predict occupancy in selected loading zones most of the time. The data can be used to strategically locate loading zones for future programs. And the students made other recommendations, like better marketing for the program to increase participation, expansion to more neighborhoods, and integration with more widely used navigation apps. The upshot, after all the data analysis, said Samriddhi Khare, one of the students who led the project, is a better quality of life for city residents.