March 25, 2024

Animating Climate Science, One Frame at Time

By Laney Myers

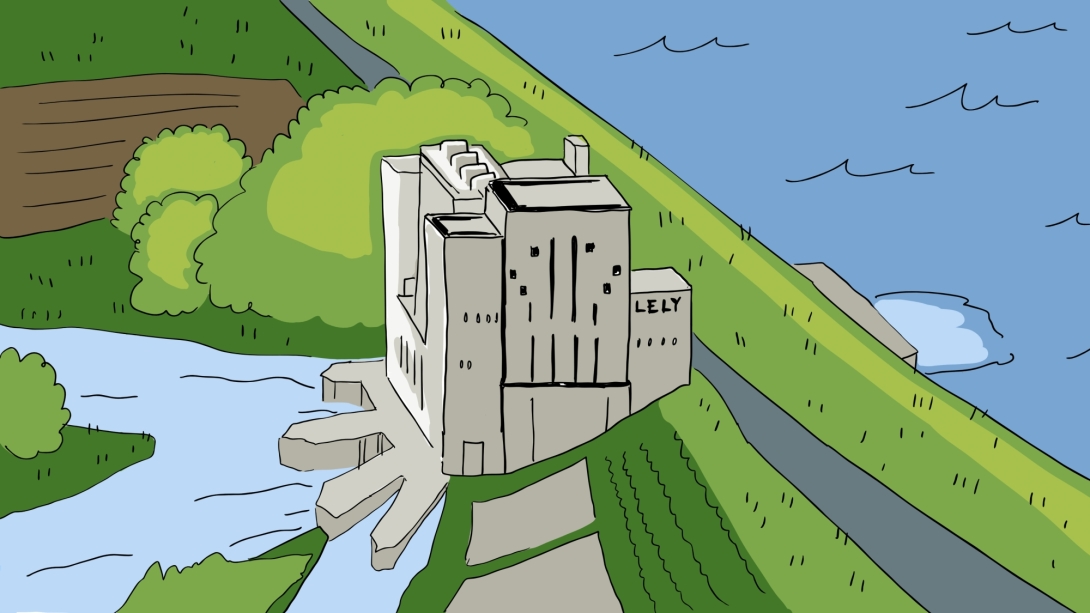

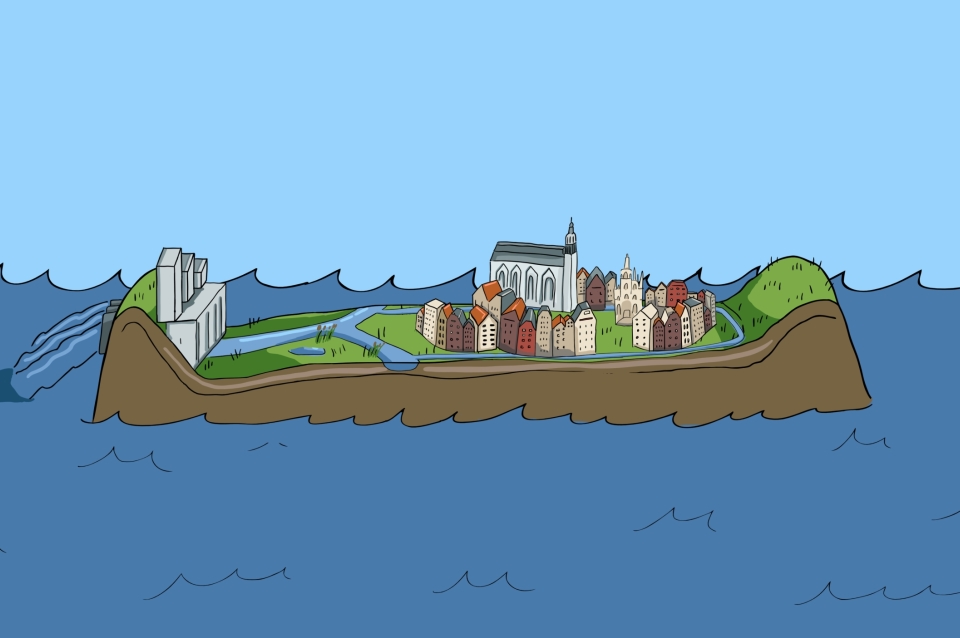

A still from 'Why was Sigmund Freud interested in the Afsluitdijk?", the latest video from the Penn Animation as Research Lab, depicts a Dutch polder.

Expand Image

Expand Image