May 6, 2024

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Areas

From Fall 2023 to Spring 2024, the Department of Historic Preservation at the Stuart Weitzman School of Design held four roundtable discussions considering the intersection of historic preservation and society, public history, design, and science. Panelists from across the country and world joined Penn faculty to consider the future of built heritage studies and professional practice and Penn’s role in shaping both.

Over 50 years ago, several critical international and national heritage preservation laws, policies, and institutions helped define the modern world after World War II, most notably the ICOMOS Venice Charter, and, in the US, the National Historic Preservation Act. Today, with critical reflection of what has been accomplished and ignored, and recognition of the enormous existential challenges we all face as the climate crisis looms large, we need to reconsider preservation’s role and status as a cognate field of study and practice.

As times change, how should historic preservation change? How do we continue to articulate the value of heritage conservation as a public good, build support and funding for preservation among a broader polity, or reconcile the field’s embrace of markets with our fundamental need to resist market logics? How do historic preservation and the larger global concern for heritage conservation continue to engage and challenge the design of the built environment—concerned not only with creating new forms and sites, but rediscovering and regenerating lost and discarded places, narratives, and experiences and safeguarding these resources as the natural world disappears?

Key themes from these conversations were compiled in white papers for PLATFORM, an online journal dedicated to conversations about the built environment. Below, explore the recordings from our four public panels, and find links to read more about the conversations on PLATFORM.

Black Wall Street mural by Donald “Scribe” Ross, north side of I-244 at N. Greenwood Ave., Tulsa, Okla, completed 2018. Photograph courtesy U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

Preservation Futures: Society

“How does historic preservation serve society? What is its role — intellectual, political, and practical — in shaping the built environment? What kind of preservation field is needed by contemporary societies, and what will future societies demand?”

This conversation was convened by Amber N. Wiley and Randall Mason and, who welcomed preservation planning scholar Fallon Samuels Aidoo, archaeologist Kimberly D. Bowes and social scientist Camille Z. Charles.

In their PLATFORM piece, Wiley and Mason tackle the trickiness of the term “heritage,” and discuss how their panelists bridge the disconnect between the preservation field’s formal institutions and the people it serves.

“Our intent was to reconsider the nature of preservation as a field of study and practice; to understand the ways in which preservation draws on the knowledge, insights, and ideas generated by social scientists; and to explore how preservation connects social histories (from the ancient to the recent past) to contemporary social reform.”

Rittenhouse Street Elevation of Mount Vernon Baptist Church (originally Bethel A.M.E. Church). Photograph by Aaron Wunsch, 2019.

Preservation Futures: History

“At a moment when history has come under increased public scrutiny, what opportunities are there for leveraging and elevating the role of history in historic preservation’s drive to serve a more just future? How does the practice of history illustrate why the natural and built environments matter?”

Sarah Lopez and Francesca Russello Ammon were joined by architectural historian Aaron Wunsch, urban design historian Elihu Rubin, and environmental historian Jared Farmer, to interrogate history’s role in shaping the theory and practice of historic preservation.

On PLATFORM, Lopez and Ammon explore this issue using entry points from each of the panelists’ work: Rubin spoke about igniting public memory around the New Haven Armory before it gets targeted by demolition; Wunsch described working with Black congregations in Philadelphia who, he argues, have long practiced adaptive reuse; finally, Farmer puts historic preservation in conversation with environmental science to advocate for writing histories of places as ecosystems.

Heritage Landscapes LLC reshaped this ecosystem in Jackson Park, Chicago. Photograph by Robbie Sliwinski, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, courtesy Heritage Landscapes.

Preservation Futures: Design

In addition to the challenge of “providing a future for an asset that is valued for its past,” design in historic settings is under “ever-increasing pressures.” These include the need for historic preservation training for design professionals, new frameworks to care for aging buildings—and, of course, threats posed by climate change.

In this roundtable, David Hollenberg and Nathaniel Rogers speak with three designers specializing in the historic built environment: Dominique Hawkins of Preservation Design Partnership, Stephen Kieran of KieranTimberlake, and Peter Viteretto of Heritage Landscapes.

The conversation delves into these longstanding and newly arriving issues, while turning for inspiration to historic landscape design, which works “directly alongside nature and time”: “This model of a vibrant and dynamic ecosystem offers a potential analogue for the preservation of districts and regions, where change is managed in such a way to promote the overall health of the system.”

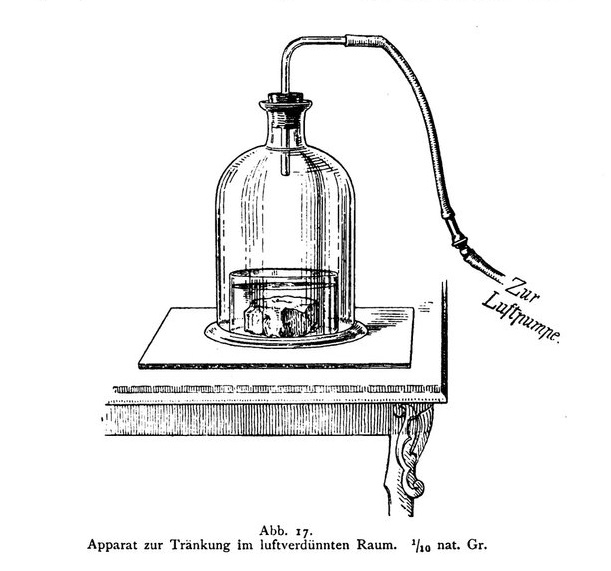

Illustration from Friedrich Rathen’s Die Konservirung von Alterthumsfunden, the first conservation handbook, published in 1898.

Preservation Futures: Science

The field of conservation—that is, the scientific study of the material reality of cultural works—charts its origins to the earlier craft-based field of “restoration.” The turn to a scientific methodology based in chemistry and later physics came in the 1930s; today, many disciplines across the natural and social sciences contribute to the documentation and analysis of cultural heritage.

The interdisciplinarity of the field of architectural conservation was a starting point for this conversation moderated by Frank Matero, Chair of Historic Preservation. Panelists were Jeanne-Marie Teutonico, architectural conservator formerly with the Getty Conservation Institute, Heather Viles, professor of biogeomorphology and heritage conservation at Oxford University; and George Wheeler, senior scientist at Highbridge Materials Consulting.

The conversation began by examining where science stands in relation to built heritage conservation, and turned to how this relationship is changing—in the face of postmodern skepticism of absolute truths, for example, as Wheeler mentioned. Viles underscored that science is never “fixed,” “but rather constantly developing and seeks to challenge existing norms through the positing of new theories and methods.”

Expand Image

Expand Image