October 17, 2017

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

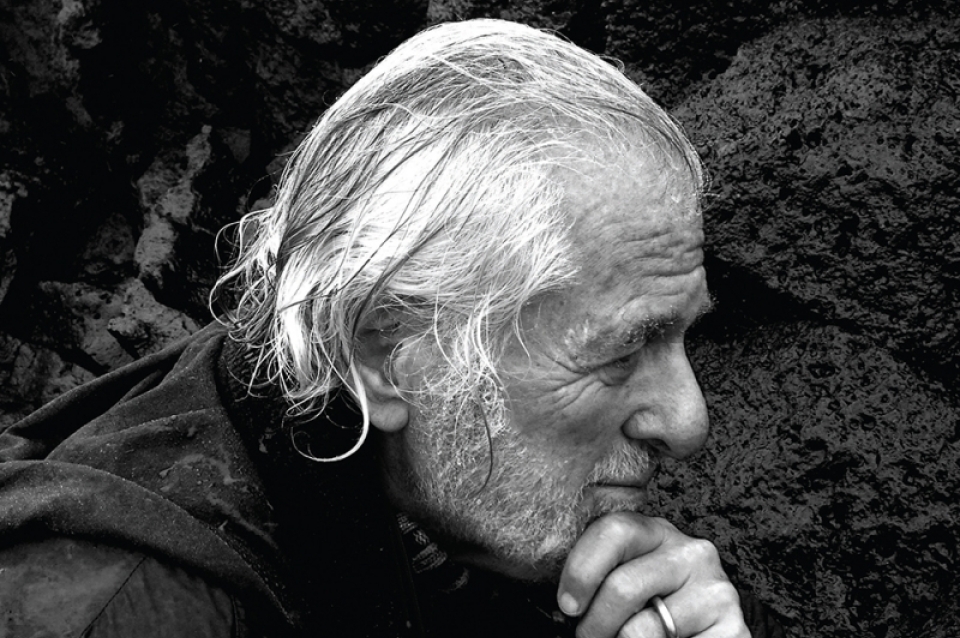

If there were a master class on curiosity, PennDesign alumnus Richard Saul Wurman (BArch’58, MArch’59) would be a natural to teach it. Not 12 hours after the launch of his latest book, UnderstandingUnderstanding, which chronicles his life in design and network of creative associates, he was looking forward to breakfast with Dr. Ron DePinho, a leading cancer researcher and former president of the world’s largest cancer center, whom he was meeting for the first time. Why? Because he wanted to know more about Dr. Pinho’s studies of the molecular underpinnings of cancer, aging, and degenerative disorders.

In 1955, Wurman enrolled at Penn, where he took courses every day of the week—more, by his account, that any undergraduate had done before. “All the courses seemed to go together in my head,” he explains. His studies ranged from Inuit archeology to Medieval illuminated manuscripts, but he chose to major in architecture.

He found his passion in cartography, and without the aid of a computer, produced an urban atlas that earned him $100 from Lou Kahn, who hung it in his studio. The two became friends, going to baseball and football games together, and dining at Wurman’s family home.

“I love maps,” Wurman writes. “In fact, I think everything is a map of something.”

Kahn enlisted Wurman’s help for projects like the first of two floating concert halls he was commissioned to design, in 1960; Wurman traveled to London in 1961 to help build it. (A sketch now on view at PennDesign’s Architectural Archives for the exhibition Louis Kahn, Barge Architect bears the notation “Dear Ricky – Excuse most hurried drawing in charcoal.”)

Meanwhile, Wurman reluctantly confided to Kahn that his interests weren’t limited to designing buildings or even the built environment. To Wurman’s surprise, his mentor encouraged him to do different things. To this day, he credits the legendary architect for “giving me permission, and I needed permission.”

Meanwhile, Wurman reluctantly confided to Kahn that his interests weren’t limited to designing buildings or even the built environment. To Wurman’s surprise, his mentor encouraged him to do different things. To this day, he credits the legendary architect for “giving me permission, and I needed permission.”

Wurman’s curiosity is so intense it sparked a global media organization. In 1984, he organized a conference that brought together leading minds of the day in technology, media, and entertainment—it was the first TED event. Operated as a nonprofit, today the ubiquitous speaker series is nothing short of a cultural juggernaut. Years ahead of the Internet, TED was arguably the world’s first platform for innovation. Exhibit A: WIRED magazine was launched at the first event. “There’s a lot of horizontal movement between disciplines,” Wurman explains. “The TED conference was about their convergence.”

TED’s runaway success aside, Wurman has also seen setbacks. He found himself destitute at 45, having been fired as dean of Cal Poly and forced to close his architecture firm. For all that, he still considers himself an architect. For him, it’s a way of understanding the world more than a profession or set of skills. He points to historic figures like “gentleman’s scholar” Thomas Jefferson, who built architectural follies compulsively. Consider the usage of the word “architect,” Wurman points out. One is an “architect” of foreign policy, and not an “author”; the practice of architecture consists of systems design rather than physical design.

UnderstandingUnderstanding (Oro Editions, 2017) is celebration of both curiosity and visual languages, with Wurman as our guide to specimens sacred (Ecclesiates) and profane (a Wall Street Journal guide to money and markets). Wurman likens the book’s introduction to a dinner party, which is also an apt metaphor for the whole. Along with Kahn, who’s represented by lectures and excerpts from his notebooks, the “guests” in Understanding Understanding include legendary designers like Charles and Ray Eames, Milton Glaser, David Kelley, and Stefan Sagmeister; scientists David Ferrucci and Geoffrey West; and breakout journalists like Steven Johnson, Peter Menzel, and Walter Mossberg, who contribute both visual and textual essays.

Tellingly, it’s an architect’s work that occupies the center of the book. In a chapter on Frank Gehry, Wurman presents a selection from 4,470 photographs of the 1,000 models Gehry produced as studies for his residential high-rise at 8 Spruce Street, New York.

In part, the book is a primer on entrepreneurialism: there are contributions from author and educator Juan Enriquez, an expert on the genomic code, and venture capitalist Kai-Fu Lee, who developed the first speaker-independent, continuous speech recognition system. Tellingly, though, it’s an architect who occupies the center of Understanding Understanding. In a chapter on Frank Gehry, Wurman presents a selection from 4,470 photographs of the 1,000 models Gehry produced as studies for his residential high-rise at 8 Spruce Street, New York.

As you might expect, maps figure prominently in the book, including annotated maps of Paris, Tokyo, and New York from Wurman’s popular series of Access Guides to major cities published beginning in the 1980s. “I love maps,” he writes. “In fact, I think everything is a map of something.”

At 708 pages, UnderstandingUnderstanding is too short, when you consider just how productive Wurman’s career has been. Take, for example, Olympic Access, the television viewer’s guide to the 1984 games that he did for the L.A. Olympic Committee, enlisting sports writers as well as illustrator Michael Everett to decode all the events for non-athletes. It’s the kind of project that most designers would be glad to have one of, but Wurman has won many such assignments.

What’s next for Wurman? He’s hoping to encourage designers, scientists, and others to expand their intellectual horizons by bringing together leaders in their fields for public conversations. “The learning process is about asking questions,” he insists. While it’s early in the planning stages, he already has his sights set on people like Lisa Randall, a particle physicist who is Frank B. Baird, Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard.

One thing is certain. “Even when I get a haircut, I’m an architect,” Wurman says.

UnderstandingUnderstanding is available online.

Expand Image

Expand Image