November 12, 2021

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Tags

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

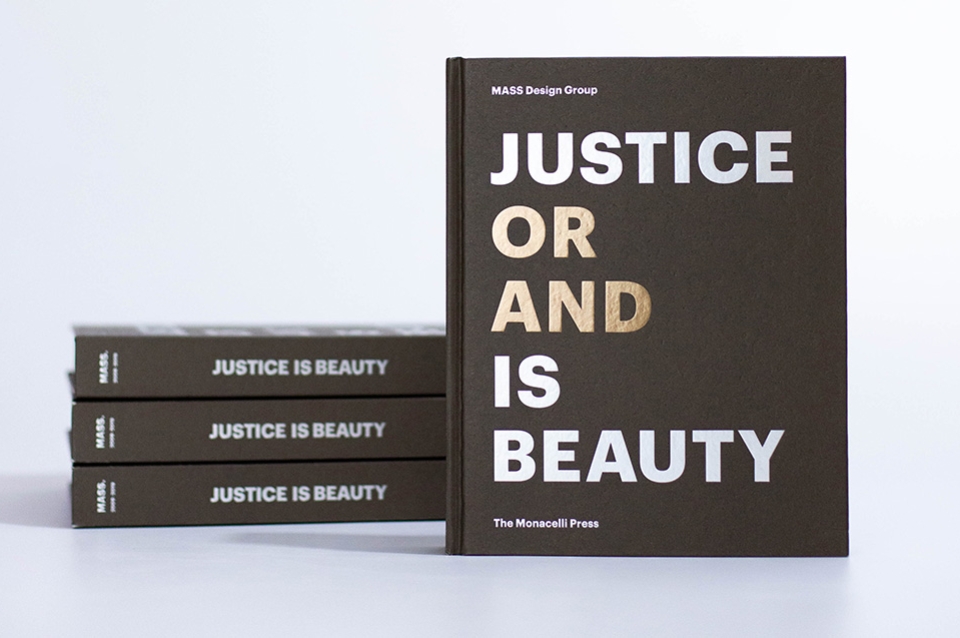

Justice is Beauty (The Monacelli Press, 2019) highlights the work of MASS Design Group, an architecture firm based in Boston and Kigali, Rwanda. In this excerpt from the introduction, Michael Murphy, the founding principal and executive director of MASS, describes how the firm got its start in the midst of the economic downturn of the late 2000s.

In architecture school in 2006, the mood, it was ascendant. We were told that employment rates were the highest they had ever been. The era of stars in architecture was at an apex, and architects sold as brands, named. In the air was invincibility and promise. And for the first time, my future looked secure.

As for buildings, they were described as heroic gestures; what and who we discussed reaffirmed that heroism. Success was a simple formula: work relentlessly, start a practice, build expressive, beautiful structures. Be an architect. Then, a year into our studies, the market plummeted. The 2008 housing crisis was also an architectural crisis. Building projects across the world were stopped, architects fired along with them—and the most recent inductees were the first to go. But it was that image, that unreachable vision of what an architect should be, that plummeted alongside the Crash.

The profession’s crisis entered the existential realm. How could our art be so bound to these fragile economic forces? Who were the victims of this dream sold bundled like so many over-leveraged mortgages? What is the core of our values that is not for sale? How complicit were we in this crash and the dust and smoke and fire that swirled in its aftermath?

The Great Recession arose from the predatory housing marketplace. The American dream of the safety and security of a home—that foundational architecture of property and family—ignited the worst financial crisis since the 1930s. One thing was clear, we were not innocent bystanders in the dreams it wrecked or the havoc and injustice the recession left in its wake.

It was December of that first year of school, and Dr. Paul Farmer spoke to the college about the injustices of global healthcare access.

To Dr. Farmer, healthcare access is also about housing access. “If people don’t have access to housing, and food and work, then healthcare will only stem the bleeding, not address the chronic conditions of why the bleeding started in the first place.” We needed a social structure, not a tourniquet. Whole and just healthcare, as his organization Partners In Health demonstrated, provides not only drugs and care, but also hospitals, and then schools, and roads to them, and houses alongside them.

Access is a moral and economic problem, in Dr. Farmer’s telling, but it is also a spatial problem. And buildings play an essential role, then, in the delivery of our rights as citizens.

In all of the lessons in design school, I could not remember anyone framing the value of buildings in such a stark and essential way. Here, architecture was in the realm of rights, but like other rights sold in the open marketplace, it had become accessible only to those who could pay for it.

Architecture is not agnostic about ethics. As with art, the political is inherent in architectural choices. Architecture points forward, it must consider the environment and the society around it. The utopian impulse is often too intoxicating to ignore. But a building’s full societal impact resists simple description, and misleading ambivalence. The choice between two opposing, distinct, and polarized types of architecture is an attractive shorthand: the architecture of sweeping forms, brand-name auteurs, and beauty; or the architecture that addresses social concerns such as housing, poverty, and economic justice.

But why must we make such a choice? Is it even possible to choose? The architect and theorist Giancarlo De Carlo called this the Bread and Roses problem—what we might term the Beauty and Justice dilemma.

The story goes that when De Carlo was a fiery editor at the Italian publication Casabella Continuità in the 1950s, his colleague, the architect Ernesto Nathan Rogers, posed a question to him: if you could only choose one, which would you choose: Bread or Roses? Justice OR Beauty?

Provoked, De Carlo realized it was not a choice we can make. We cannot choose one, he concluded: one is an end, the other a means. The two are intertwined in the built world. Instead, we should ask: what is the societal impact of beauty? Or what does a more just society construct?

He called this the False Dichotomy. And once we see it, we cannot unsee it. It appears everywhere. And it appeared to me that night in Dr. Farmer’s lecture.

Rwanda in 2008 was freshly tilled soil. Streets were swept, lawns manicured, education and healthcare guaranteed. Rwanda had seen the depths of humanity’s fall. The genocide of 1994 stripped a people of human dignity, and a generation of lives.

Change is possible, Rwanda shows. After focused investments in health and education, housing, economic reconstruction, and reconciliation, Rwanda was abundant and hopeful in 2008. It was also insulated from the financial collapse in the United States; instead of firing architects, it was hiring.

Bruce Nizeye, the lead engineer for Partners In Health, drove me to a clinic my first weekend in Rwinkwavu. He and I went to labor with Dr. Farmer and a collection of volunteers leading an umuganda—a shared day of service. The task that morning was to beautify a clinic’s grounds. People were planting trees, marking pathways in brick, and moving boulders. Dr. Farmer was directing the construction of a fish pond—a necessity, he insisted, for any medical facility. “Dignification,” he explained, was as essential to healthcare as delivering medicine.

The construction of dignity. The work and toil and maintenance that creates beauty produces a profound sense of worth. Human dignity, that feeling that we matter, that someone has noticed me for who I am, is found in those processes of beautification, the tending of the garden, the discovery that a building’s design locates us in place, that we are respected for who we are. Dignity navigates the oscillation between me and we. The construction of dignity erodes the false dichotomy.

To be awakened to the false dichotomy is to notice it in other zero-sum scenarios. When one prominent doctor prodded our team with questions, asking “aren’t more drugs and more beds a better investment than fancy buildings,” he was constructing his own opposing binary, that scarce resources require sacrificial choices. But dignity asks the counterfactual: What is sacrificed in lives, in communities, in self worth, when we isolate access to dignity only to those who can pay for it? Dr. Farmer would ask us, What is the cost of not having architecture?

The choice, our choice, was not between a beautiful building or a basic building; the choice was to lower expectations about what was possible, or not to. Something clicked. To be an architect should be to fight for the beauty and dignity that others have been denied. And there, at the bottom of that fish pond, was the existential argument for architecture’s value. Justice AND Beauty made possible. A choice we couldn’t afford not to make.

Expand Image

Expand Image