Excerpt from ‘Kenzō Tange and the Metabolist Movement’

A new book gives an expanded account of Tange's and Metabolists' radical notions of urbanism

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

A new book gives an expanded account of Tange's and Metabolists' radical notions of urbanism

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

Now in its second edition, Kenzo Tange and the Metabolist Movement: Urban Utopias of Modern Japan (Routledge), by Zhongjie Lin, associate professor of city and regional planning, lays out the story of the seven architects and designers who, amid Japan’s political turbulence in 1960, founded Metabolism to propagate radical ideas of urbanism. This excerpt, from the book’s final chapter, describes how their utopian concepts reflected fundamental issues of cultural transformation and addressed environmental crises of the postindustrial society.

Seeing the Future from the Past

This book studies the works of Kenzō Tange and Metabolist architects as visionary urbanists during the formative years of this avant-garde movement inaugurated at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo and concluded at the Osaka Expo in 1970. Their careers as architects and urban designers last much longer than this decade and have maintained a very high level of productivity and impact until recent years – many of them became international celebrities, including three Pritzker Architecture Prize laureates. The fall of Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower in 2022, along with Arata Isozaki’s death at the end of this turbulent year during the COVID-19 pandemic, symbolically marked the end of an era.

In a sense, this period of more than six decades has witnessed a complete cycle of rise and fall of the Metabolist movement. Despite the unfortunate, yet almost inevitable, demolition of the Capsule Tower, the enormous enthusiasm stimulated by the campaign to save this modern landmark seems to suggest reincarnation of the intangible legacies of metabolism within the current architecture culture, inspiring both scholarly reflections and professional innovations. In Project Japan, Rem Koolhaas extols Metabolism as the “last movement that changed architecture.”(1) This impassioned comment attests to the significance of Tange’s and Metabolists’ early works in the context of the contemporary architecture and society.

Such recognition, however, did not remain consistent during all these decades. Since the end of the 1970 World Expo, the passions, exposures, and admirations, along with controversies around this movement, had gradually passed into dreariness and silence for the remaining years of the twentieth century. It was not until the first decade of the new century that interests have risen again in studying Metabolism as well as other avant-garde movements that had tried to break away from modernism during the postwar decades. A new generation of historians engaged themselves in reevaluating this recent history, and architects and planners turned to view the Metabolist concepts and imageries as inspiration for possible breakthroughs in design.

Despite the renewed interests in the professional communities and the new outputs in scholarship, the Metabolist urban discourse and its impacts on the modern society remain ambiguous, largely due to the lingering attitude toward “megastructure” in historiography dominant during the twentieth century. One also has to move away from the tendency of using Western architectural vocabularies (such as béton brut) to interpret the Metabolist movement, in order to bring a broader point of view concerning Tange’s and Metabolists’ works and to recontextualize their urban visions within Japan’s political and social contexts from which their radical concepts emerged. This shift leads to the rediscovery of other important discourses of urbanism than megastructure, which have emerged from Metabolism, including group form and “ruins.” All three concepts embody the bud for a model of city design and each addresses urban growth and transformation from a particular angle. Their ramifications still influence city building today and contribute to the dynamics of contemporary metropolises shaped by differing ideologies and socioeconomic visions.

The meaning and influence of Metabolism in the social sphere deserve particular attention. Japan’s urban reconstruction, economic miracle, and cultural resurgence since the 1950s provided an evocative setting for Metabolists’ utopian approaches to architecture and planning. Metabolists’ visionary projects of the city, in turn, carried the ambitions to reinvent Japanese identity and to address critical issues of an emerging postindustrial society. Their work stood at the intersection of urbanism and utopianism, reflecting currents of aesthetic, technological, and ideological changes in the postwar Japanese society. The endeavors of using futuristic urban design to catalyze societal change, expressed in a series of original ideas and powerful imageries, represent an important part of Metabolism’s legacy to our present world and connect the Metabolist concepts to the current discussions of technology and society informed by universal networks, mobile technologies, and digital media. This continuity provides a useful lens for further investigation of urbanization in Asia.

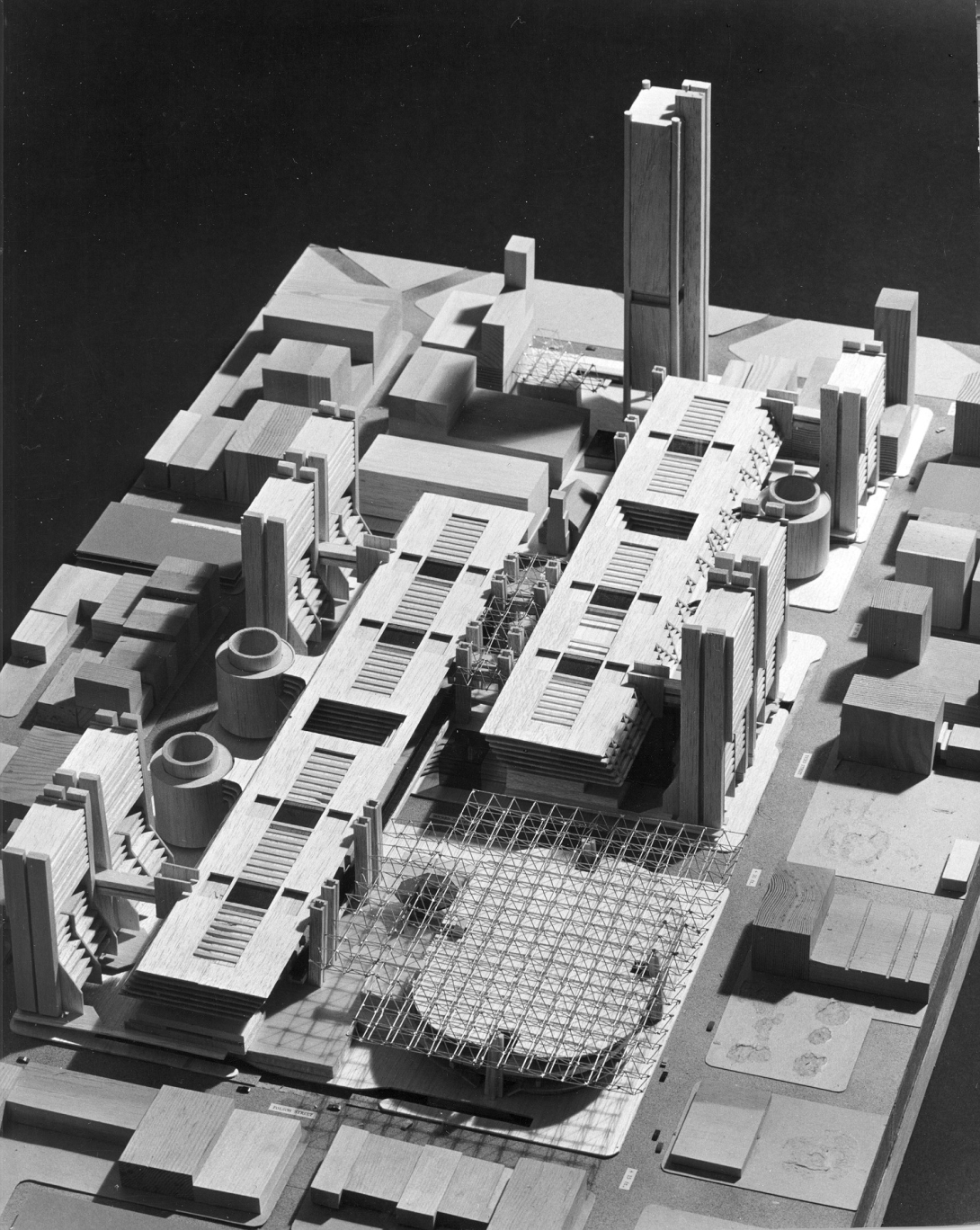

Kenzō Tange, Plan for Yerba Buena Gardens, San Francisco, 1967. Model view.

Revival of Metabolism

Reyner Banham’s 1976 Megastructure exemplified the prevalent viewpoint to understand Metabolism from Western perspective prior to the twenty-first century, although it was not the first book featuring Metabolism’s work outside Japan and neither did Banham coin the term megastructure.(2) In fact, “megastructure” first appeared in Fumihiko Maki’s essay on the “collective forms.”(3) When Maki’s writing was published in 1964, Metabolism just became an international phenomenon with its MoMA debut. Kenzo Tange’s Tokyo Olympic Gymnasium, completed in the exact same year, made a strong statement about Japanese architects’ technological capacity and modern aesthetic. The World Exposition in Osaka six years later strengthened Metabolism’s identity with a megastructural plan by Tange and numerous pavilions by Metabolists conceptualized in a similar method, manifesting the influence of this concept through the 1960s.

While it dominated major international events and saw its influence in large-scale urban developments throughout the world, megastructure had become more controversial since the late 1960s and encountered stronger resistance against attempts of applying it in urban centers. Massive protests forced the local authorities to abandon Tange’s initial plan for Yerba Buena Gardens in San Francisco and Paul Rudolph’s Lower Manhattan Expressway project in New York, both designed in 1967. Unsurprisingly, the outcome of megastructure in the real world hardly matched its theoretical promises. In Megastructure, Banham criticized the “mind-numbing simplicity” of the Metabolists’ theoretical program and accused Tange’s Tokyo Bay project of having a “destructive influence” on the French and Italian megastructural projects.(4)

Impacted by the global energy crisis and resultant economic downturn in the 1970s, megastructure’s popularity among architects and the public continued to wane, and criticism became dominant. Written in the aftermath of the worldwide student uprisings and the dawn of environmental movements, Banham’s book generalized a series of ideas and movements with shared interest in massive intervention dependent on cutting-edge technologies, but he ridiculed them as “urban futures of the recent past” and “dinosaurs of the modern movement.”(5) His skepticism was typical of the attitude toward Metabolism and the postwar avant-gardes for the next few decades.

Opinions regarding these visionary urbanists of the 1960s, including Team 10, Archigram, Super Studio, Yona Friedman, and Metabolism, have undergone another considerable, if subtle, transition in architectural criticism in recent years. It is manifest in scholarly works that have seen a strong revival of interest in Metabolism. Several new accounts came out in the last decade since the publication of the previous edition of this book in 2010, and a few high-profile exhibitions have been organized, either focusing on Metabolism or including substantial materials to feature this movement.(6) These exposures in presses and galleries, occurring at an intensity rarely seen in architectural scholarship, testify the rising interest in the Metabolist movement, which is constantly linked to the current topics of discussion in architecture and urbanism. Notable about these recent accounts, compared with earlier, rather fragmental studies of Tange’s and Metabolism’s works, is the shift of emphasis from architectural creativities to urban propositions. The attitude toward its avant-gardism is also changing. Although criticisms of megastructure remain relevant, an appreciation of their futuristic approach to city design has become the main thesis.

Minato Mirai 21, Yokohama.

Among other factors, globalization and economic neoliberalization in the last few decades have produced enormous wealth that had never been imagined before, creating scenes of universal prosperity and cultivating an optimism not unlike the mentality during Japan’s economic miracle. This helps make Metabolism and its ideas popular again. It is also a glorious age of media, in which imageries, paper architectures, and ideal cities often circulate more widely than built works. Metabolists and its contemporaries, like Archigram, Cedric Price, and Situationist International, have been considered by historians as the first generation of designers who approached architecture and urbanism as media.(7) They tended to incorporate advertisement, visual materials, and electronic technologies into their designs, and their works stressed the immaterial quality of architecture over concrete forms. They used architectural drawings and models as well as nontraditional methods of representation like collage, cartoon, electric display, and video to present ideas from a living pod to an ideal city. Metabolists were also versed in curating exhibitions and producing publications, and familiar with television programs. The affinity of their work to modern media and their futuristic approach to design resonate with the lifestyle and aesthetics of the current age.

Metabolism also addresses other aspects of the contemporary urbanism. As the news and debates about the demolition of Nakagin Capsule Tower continued to circulate worldwide, architects have not only rediscovered Metabolism’s cutting-edge concepts of prefabrication, modularity, recyclability, and adaptability, but have also come to appreciate their extraordinary visions of the modern society. Architectural critic Nicolai Ouroussoff argues:

The Capsule Tower is not only gorgeous architecture; like all great buildings, it is the crystallization of a far-reaching cultural ideal. Its existence also stands as a powerful reminder of paths not taken, of the possibility of worlds shaped by different sets of values.(8)

In fact, their structures like the Capsule Tower as well as many unrealized projects were not designed as a solution for a specific site and program, but rather a prototype for an alternative urban form and social organization in the postindustrial age. Although almost none of the Metabolists’ ambitious schemes of city design was carried out – with the only exception of the Osaka Expo, a six-month trial of the future city – their urban utopias constitute invaluable intellectual legacy from the 1960s. To a certain extent, the utopian spirit in their urban projects has preserved the essence of these visionary ideas against aging, as the plans transcend their immediate context to address broader and long-term issues facing the global cities. These experimental projects provide theoretical models to explore possibilities of modern technology in shaping the built environment and serve as great precedents for contemporary urbanism.

1) Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist, Project Japan: Metabolism Talks… (Cologne: Taschen, 2011), 12.

2) Reyner Banham, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past (New York: Harper & Row, 1976).

3) Fumihiko Maki, Investigation in Collective Forms (St. Louis, MO: Washington University School of Architecture, 1964).

4) Banham, 47, 57.

5) Ibid., 7.

6) The first edition of this book, published in 2010, was developed from the author’s dissertation submitted to University of Pennsylvania in 2006. A Chinese translation of the book was published in 2011. Historian Hajime Yatsuka published a book in Japanese entitled Metabolism Nexus in 2011, the same year he co-curated the exhibition “Metabolism: The City of the Future” at Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. Architect Rem Koolhaas and curator Hans Obrist published their interviews with Metabolist architects in the book Project Japan: Metabolism Talks… in 2011. They were followed by books written or edited by Agnes Nyilas (2018), William O. Gardner (2020), Casey Mack (2022), and Raffaele Pernice (2022). Koolhaas and Obrist, Ibid; Mori Art Museum, Metabolism: The City of the Future (Tokyo: Mori Art Museum, 2011); Agnes Nyilas, Beyond Utopia: Japanese Metabolism Architecture and the Birth of Mythopia (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2018); William O. Gardner, The Metabolist Imagination: Visions of the City in Postwar Japanese Architecture and Science Fiction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020); Casey Mack, Digesting Metabolism: Artificial land in Japan 1945–2022 (Berilin: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2022); Raffaele Pernice ed., The Urbanism of Metabolism: Visions, Scenarios and Models for the Mutant City of Tomorrow (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2022).

7) The following books explore the relationship between architecture and media in the postwar avant-gardes: Simon Sadler, Archigram: Architecture without Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005); Stanley Matthews, From Agit Prop to Free Space: The Architecture of Cedric Price (London: Artifice Books on Architecture, 2007); Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology (Bureau of Public Secrets, 2007).

8) Nicolai Ouroussoff, “Future Vision Banished to the Past,” New York Times, July 6, 2009, accessed December 20, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/07/arts/design/07capsule.html.