December 6, 2024

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

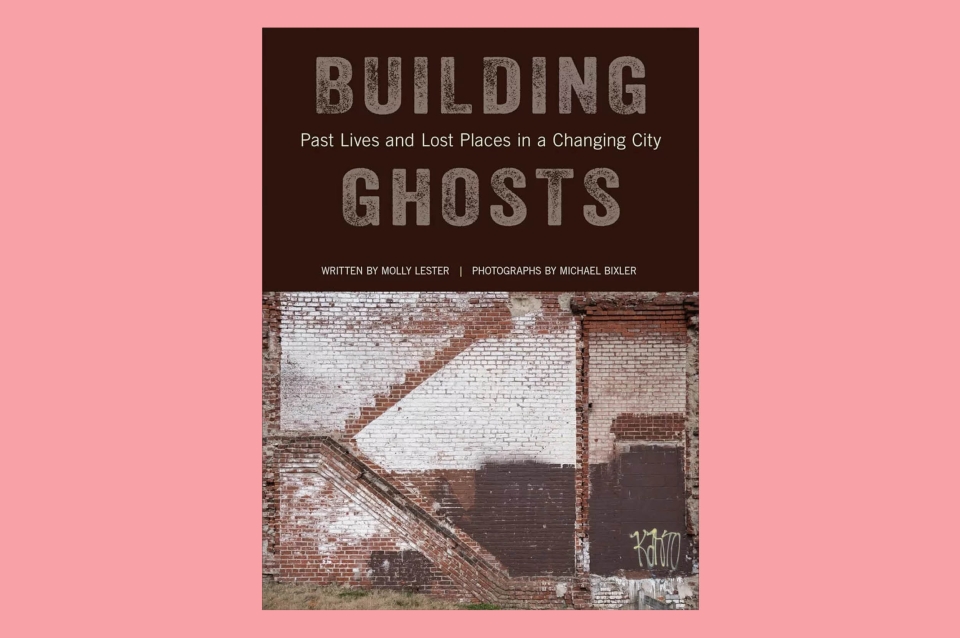

In her new book from Temple University Press, Building Ghosts: Past Lives and Lost Places in a Changing City, Molly Lester (MSHP’12), a lecturer in historic preservation and the associate director of the Urban Heritage Project, collects the physical traces of demolished buildings. Along with photographer Michael Bixler, the managing editor for Hidden City Philadelphia, Lester located and documented hundreds of so-called “building ghosts” from across Philadelphia. In an excerpt, Lester describes how this collection was assembled and categorized and then gives an example of the close reading done for each site captured in the book. The work was funded by a grant from the Sachs Program for Arts and Innovation.

Introduction

“Building ghosts” are the imprint and last impressions of a demolished building, left behind on the walls of the neighboring structures. Physically, they are architectural remnants that can be found only in a rowhouse city such as Philadelphia, where the loss of one structure leaves a tangible mark on its neighbors. These ghosts can be ephemeral or enduring, quickly revealed and replaced in a neighborhood seeing rapid change or unveiled and exposed indefinitely in a neighborhood that hasn’t seen new construction in a long time.

In the simplest sense, these ghosts are artistic objects: beautiful, sometimes legible, and confounding—all at once. But these vestiges (of structures, stairs, wallpaper, closets) are also legacies, hinting at the lives lived within these walls, the communities shaped around these buildings, and the ways in which we create and erase history in our changing cities. Our book about this phenomenon investigates, mourns, and celebrates these ghosts in our midst, retracing their structures and selves and dwelling in the moment between a place’s loss and its erasure.

1025 Buttonwood Street (Photographed December 3, 2020). Photo: Michael Bixler

1025 Buttonwood Street

Constructed pre-1860

Demolished in 2020

By the time she took lodgings at 1025 Buttonwood Street, twenty-three-year-old Edith Fantini had already called Germany, France, Russia, and Venezuela home. If modern passports had existed then, hers would have had more stamps than the rowhouse had rooms. Born in the town of Breslau (part of Prussia at the time, now known as Wrocław and part of Poland), she studied in Leipzig and Paris, developing a love of languages. When an opportunity to work as a governess arose, she ventured to the city of Odessa, situated on the Black Sea and within Russian borders. At some point, with at least three languages on her tongue, she set out to learn a fourth; this one required a transoceanic crossing, as she set sail for Puerto Cabello, Venezuela. She taught there until 1885, when she continued on to North America. Soon after, she landed in Philadelphia.

During the many years Fantini was traveling the globe, a modest two-and-a-half story brick rowhouse stood at 1025 Buttonwood Street. Located a block south of the grand Spring Garden Street, the block was lively in its own right, with an uninterrupted line of rowhouses on the north side and a school and police station on the south side, closer to 11th Street. It was also a convenient distance from the office at 10th and Market streets, where Fantini found a job around the same time she began renting at number 1025 in 1888. She had journeyed more than ten thousand miles to earn a commute of just seven blocks.

A fluent multilinguist, Fantini secured a post as a stenographer for French, Richards, and Company, with responsibility for interpreting the company’s foreign mail. Although French, Richards was primarily a wholesale drug company (selling legitimate pharmaceuticals alongside whiskey and bottled water to cure various ailments), it also advertised its robust trade in imported wares. The job kept Fantini busy, and she liked it, all the more so when she met Benjamin Franklin Hunter working there, too.

It was a shock, then, when the company suddenly announced in 1890 that it would shut down by the end of the year, after forty-six years in business. Its founder had died suddenly, and the company had stumbled in his absence. Fantini lamented the announcement and helped draft a brief resolution in which the staff thanked the company and parted on good terms. A newspaper remarked, “The relations between the employees and members of the firm (had) always been of the most pleasant character.”

Her years at French, Richards were not an entire loss, however. In 1892, Fantini married Benjamin Hunter; a year later, she gave birth to a daughter, Helen. By 1896 (if not earlier), she was once again making use of her language skills, offering private instruction in French and German at a rate of fifty cents per lesson.

It is unclear when Fantini moved out of 1025 Buttonwood Street. (White women were only ever intermittently included in city directories, even when they had professions outside the home to list. Black women and men, meanwhile, were almost always relegated to separate directories altogether.) She definitely lived there in 1888 and 1889, but her name does not appear at all in the city directories that follow. Nevertheless, she may have lived there until her marriage to Hunter in 1892, or perhaps she moved elsewhere in the city in 1890–1891, around the time French, Richards was heading toward insolvency. By 1896 (if not earlier), she lived in West Philadelphia.

French, Richards did not entirely fold in 1890. In the course of its liquidation, a segment of the company was sold off, merging with another outfit to become Smith, Kline, and Company. Eventually, Fantini’s company became part of what is now GlaxoSmithKline.

Edith Fantini Hunter, meanwhile, left Philadelphia in the 1890s. Perhaps the wanderlust of her younger years returned, because after about fifteen years in one place, she pulled up roots. Together with her husband and daughter, she once again called Paris home—this time, though, it was Paris, Tennessee. She died there in 1935.

Expand Image

Expand Image