July 19, 2024

Nurturing Nightlife in Music City

A new report from PennPraxis, VibeLab, and Culture Shift Team captures the vitality and vulnerability of Nashville's music scene.

By Jared Brey

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

A new report from PennPraxis, VibeLab, and Culture Shift Team captures the vitality and vulnerability of Nashville's music scene.

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

Lots of cities are known for their vibrant music scenes, but none more than Nashville, Tennessee.

Nashville’s identity as Music City dates back more than a century. Queen Victoria reportedly once described Nashville as “a city of music” after hearing a performance by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a Black choir from Fisk University. Nashville became the center of the country music recording industry in the twentieth century, and today it has 252 venues that showcase live music. More than 100 of those spaces are solely dedicated to music—one of the densest clusters of live music venues per capita of any place in the world. A few dozen independently owned and operated venues play an outsize role in cultivating the city’s musical talent. Those independent venues are increasingly at risk amid a development boom and widespread gentrification.

That’s according to a new report from PennPraxis—the applied research, engagement, and practice arm of the Weitzman School—in collaboration with VibeLab, a Berlin-based consultancy group, and Culture Shift Team of Nashville. The Nashville Independent Venues Study, released this month, was commissioned by the Metro Council in 2021 amid the economic and cultural crises brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic. But the precarity of independent venues stretches back much earlier.

“The backdrop to this whole project is that Nashville is experiencing a massive, multi-decade economic boom,” says Michael Fichman, Associate Professor of Practice in the Department of City and Regional Planning program and a senior research associate at PennPraxis. “There’s a very fast moving real estate environment, and [venue operators] are concerned about their ability to stay in their properties. The workforce is concerned about their ability to remain in Nashville. Musicians are concerned that they’re going to have to live further and further out in the county.”

Jeff Syracuse, the associate director of customer relations at BMI, drafted a resolution to commission the study while serving on the Metro Council, Nashville’s governing body, in 2021. PennPraxis and VibeLab won the commission through a competitive RFP process. The study was funded by the Metro Arts Commission, the Metropolitan Historical Commission, Metro Office of Nightlife, the Nashville Convention and Visitors Corporation, and the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce. That coalition of funding partners indicates how important live music is to Nashville’s identity. Civic leaders credit the music scene with helping to draw a growing number of tech businesses and corporate headquarters. But the growth has been “a dual-edged sword,” Syracuse says.

“In some ways it’s been detrimental to the artists and songwriters who want to take part of the dream of Nashville, that you can come here to be successful,” he says.

(Photo Chuck Adams)

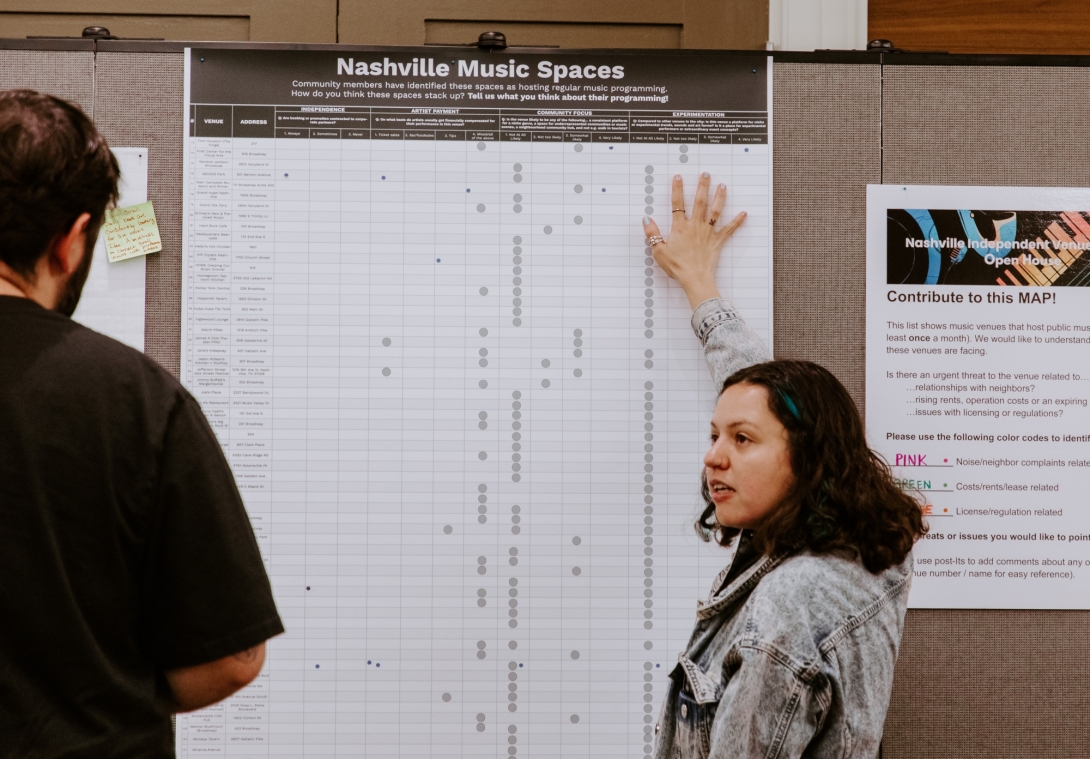

PennPraxis and VibeLab worked on the study for more than a year-and-a-half. They held focus groups with musicians and venue owners, working with local liaisons and engagement consultants from Culture Shift. Two Weitzman School students, Katie Hanford (MCP’24) and Sofia Fasullo (a Master of City Planning and Master of Urban Spatial Analytics student), were hired as PennPraxis research associates on the project. Fasullo worked on quantitative aspects of the research, compiling data on economic and property conditions in the city, while Hanford built a qualitative history of the city’s music industry and land-use development. Counter to big population centers in the northeast, Nashville’s growth has been less confined by regulation.

“In terms of land use and development, it’s kind of a free for all,” Hanford says. “This mix of boomtown development practices and this really intense music ecosystem that puts Nashville on the map has led to corporatization and some of the threats to independent venues.”

Loose regulations have in some ways been a blessing to independent venue operators. There are fewer barriers to entry for live performance in Nashville than some bigger coastal cities. But growth has complicated the picture. Rents are higher than ever, and most venues don’t own their own buildings. They’re often responsible for rising property-tax bills. Denser development has also created conflicts between venues and their new neighbors, with a growing number of noise complaints.

Growth has brought new regulations around things like parking as well, says Adam Charney, co-owner of Rudy’s Jazz Room. The club’s owners have had to work with city officials to carve out small exceptions to parking regulations so musicians have enough time to unload gear and play gigs before being ticketed. While the club is successful as a venue, rising costs have made it increasingly challenging for the business to make ends meet.

“Margins are extremely thin, much more so than any other bar or restaurant,” Charney says. “We take a lot of risk and there’s a lot of planning. I love it—we all love it. But it’s not a moneymaker. It’s something that’s a passion thing.”

The Nashville Independent Venues Study is available for download from Nighttime.org.

The Nashville Independent Venues Study includes a series of recommendations for how government and civic institutions can support small venues, which provide space for local musicians and songwriters to develop material in ways that larger corporate venues don’t. Indepdendent venues also are more likely to run community-focused programming. The recommendations include establishing a land trust to help manage costs for venue operators, making licensing and permitting processes more user-friendly, amending land-use regulations for music venues, and building a “whole of government approach” to supporting Nashville’s music ecosystem.

Many of the challenges facing Nashville’s independent venues are also pressure points in other aspects of city life, says Gregory Claxton, a planning manager in the Metro Nashville Planning Department. The booming real estate market has created affordability challenges for everyone.

“We’re transitioning from being a lower-cost city to a higher-cost city, and that’s unsettling a lot of things,” he says.

It will take time and effort to enact many of the recommendations in the report, Claxton says. Nashville’s government is constrained partly by the state in ways that home rule cities in other places aren’t. But there are reasons to hope that state and city leaders are willing to invest in the city’s live-music industry. Earlier this year, for example, the Tennessee legislature created the structure for a live music fund that could administer grants to venues and performers.

Fichman has studied nightlife and cultural economies in cities around the world. He’s currently conducting nightlife studies in Rotterdam and Copenhagen, after working last year in Montreal and Sydney. But he says Nashville is a one-of-a-kind music hub. And the fact that so many political, civic, and business leaders lined up to support the independent venues study is evidence that they recognize its importance to the city’s future.

“Most cities say they care about music, but in my experience it’s [seen as] something that’s nice to have,” Fichman says. “Here it’s something you have to have. It’s the identity of this place.”