A Preservation Plan for Philadelphia’s Tanner House

A Weitzman community partnership builds on the legacy of the 19th century's preeminent African American artist.

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

A Weitzman community partnership builds on the legacy of the 19th century's preeminent African American artist.

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

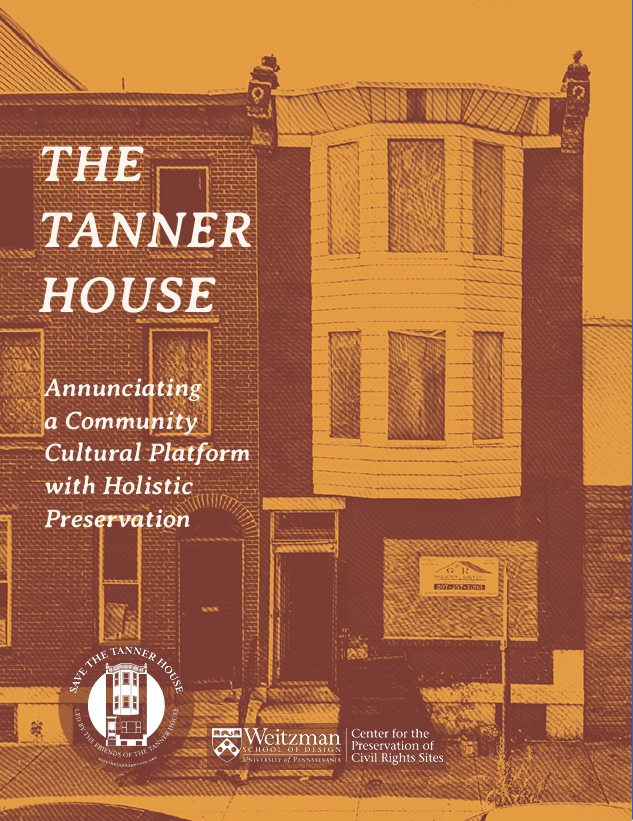

Weitzman’s Center for the Preservation of Civil Rights Sites, in collaboration with the Friends of the Tanner House, has wrapped up a year-long Mellon-funded visioning process to inform a preservation planning process for the Philadelphia home of the19th century's preeminent African American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner.

In an essay for the report, which is available for free download, Presidential Associate Professor of Historic Preservation Amber Wiley describes how the Tanner House became a National Historic Landmark in 1976 through the work of the Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation, making it among the first Landmarks nominated for its association with Black history.

Coda: Return Home

The work presented in this publication is the product of countless seeds planted that are starting to come to fruition. The coalition, conversations, and community convened by the Friends of the Tanner House (FOTH) in such a short period of time is truly remarkable. Part of this is a reflection of their approach – building on pre-existing networks, being expansive, collaborative, and communal. This success is also a testament to their nuanced approach to the stories we tell about the Tanner House, and more specifically, the Tanner family.

I offer a little backstory for context. The Henry Ossawa Tanner National Historic Landmark (NHL) was designated as such in May 1976, just two months before the Bicentennial celebration of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. This was accomplished through the advocacy of the Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation (ABC), an organization founded by brothers Robert deForrest and Vincent DeForest to increase participation of Black Americans in the Bicentennial and to direct projects that highlighted Black history, but most importantly to be a “‘vehicle’ for improving the lives of Black Americans.” The group worked to “continue the revolution” through the “process of decolonization, a movement toward self-realization and self-government by people determined not to be kept in a subject status.” Their work was by and large radical – suggesting Black historic sites for inclusion to the NHL program of the National Park Service (NPS). NHL’s are determined by the Secretary of the Interior to be nationally significant in American history and culture. Yet in the early 1970s, of the 1,200 NHLs recognized by the NPS, only 4 had been nominated for their association with Black history. ABC leaned on the social, political, and intellectual capital of an advisory board composed of Black academics, politicians, librarians, celebrities, and community leaders to conduct a broad survey of Black history sites to propose to the NPS for greater representation of Black achievement in the first two hundred years of the country’s founding.

Despite their Black revolutionary preservation aspirations at the time, ABC historians’ approach to storytelling fell in line with certain contemporary proclivities – pinpointing key actors and events to lift up in solitary celebrity. Granted, these were the unsung heroes of Black history, and American history more broadly, yet they were propped up on pedestals in ways that reflected mainstream historical approaches within the NPS. Figures like Carter G. Woodson, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., served as avatars of Black excellence for all of the Black community. Thus, the NHL nominations to safeguard their respective homes were written as such.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, in his international success, represented the long overdue recognition of Black artistic genius in the late nineteenth / early twentieth century art world that was dominated by Parisian standards and tastes. Long expatriated to Paris due to American racial prejudice that hampered his career, Tanner’s Philadelphia childhood home would stand in for him and his accomplishments. The ABC successfully put forth the Tanner site (as well as the Frances Ellen Watkins Harper House and Mother Bethel AME) as NHL nominations in the city of Philadelphia. In all, ABC managed to nominate over 70 NHLs across the country related to Black history ahead of the Bicentennial. Their enshrinement of the Tanner House with this status was indeed a way of returning Tanner’s global legacy home from across the Atlantic to the United States, to Philadelphia, and to his own Strawberry Mansion neighborhood.

These Bicentennial gains were truly a feat Black preservation strategies. ABC’s initiative remains the single most impactful strategy to designate Black NHLs in this country. But almost fifty years later, we must assess the conditions of these sites and ask ourselves, to what end?

In some cases, like the aforementioned homes of Woodson, Bethune, and King, ABC-nominated NHLs eventually became National Historic Sites – park units acquired, financed, and supported by the NPS. This condition guarantees a level of capital (both private and public) visibility and patronage that other privately held or locally managed NHLs simply do not have. For sites like the Tanner House, upkeep, repairs, and tangled title issues present multiple challenges. Additionally, Black historic sites sit in neighborhoods that have suffered from decades of systemic disinvestment, yet live with the very real threat of gentrification today. These sites face a myriad of complex challenges that Black communities have to respond to, in order to protect the long, rich legacies that are quickly disappearing from the physical landscape.

Moreover, contemporary preservation storytelling methods have turned away from our single narratives about solitary achievements, to underscore the ways that the Black community supported success through a network of relationships built and sustained over generations. That is why this second phase in the preservation and revitalization of the Tanner House is so important. Call this Black revolutionary preservation aspirations – part two. We pay homage to ABC who laid the foundation, and today we build on that foundation – brick by brick, beam by beam. The FOTH have recognized the depth and breadth of the Tanner family legacy, choosing to start their narrative with Henry Ossawa Tanner’s parents – Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner and Sarah Elizabeth Miller Tanner. Moving through the generations to include Tanner siblings, nieces, nephews, and in-laws, the FOTH have expanded our understanding of how kinship within the home safeguarded against indignities outside, and how those whose lives were nurtured within the walls of 2908 W. Diamond Street – including, but not limited to Henry Ossawa Tanner – in turn nurtured other lives from without. This is the bedrock of the Friends of the Tanner House approach, and this philosophy of expansion, communion, and fellowship will continue to guarantee the project’s success moving forward. We invite you to be a part of our return home.