September 11, 2024

Q&A: Sue Ann Kahn

Louis Kahn’s daughter describes her journey to publish the architect’s final notebook and the discoveries it holds.

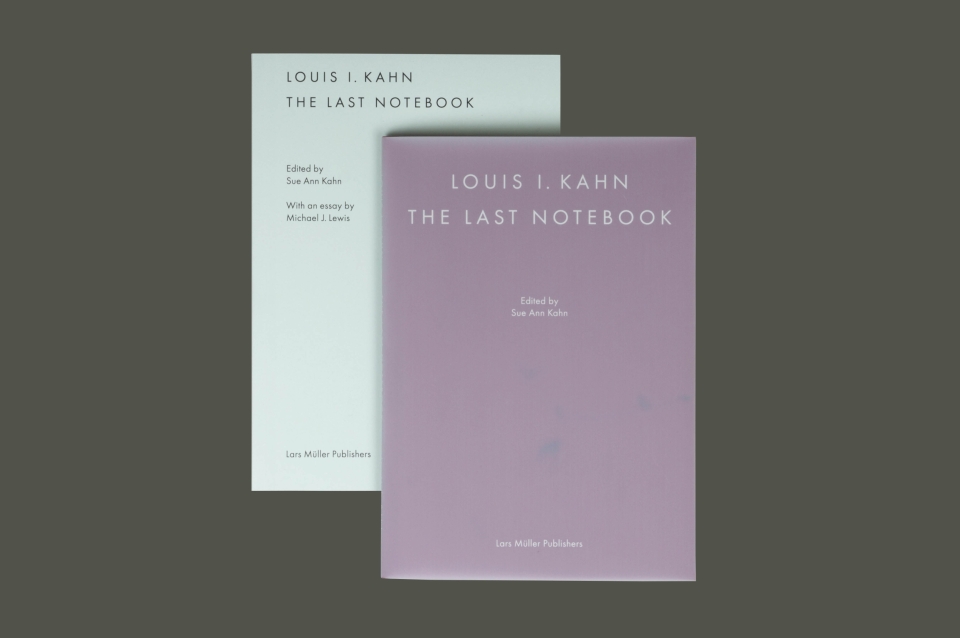

Louis I. Kahn: The Last Notebook, Facsimile and Commentary volume, edited by Sue Ann Kahn, Lars Müller, publisher.

Expand Image

Expand Image