April 16, 2021

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Areas

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

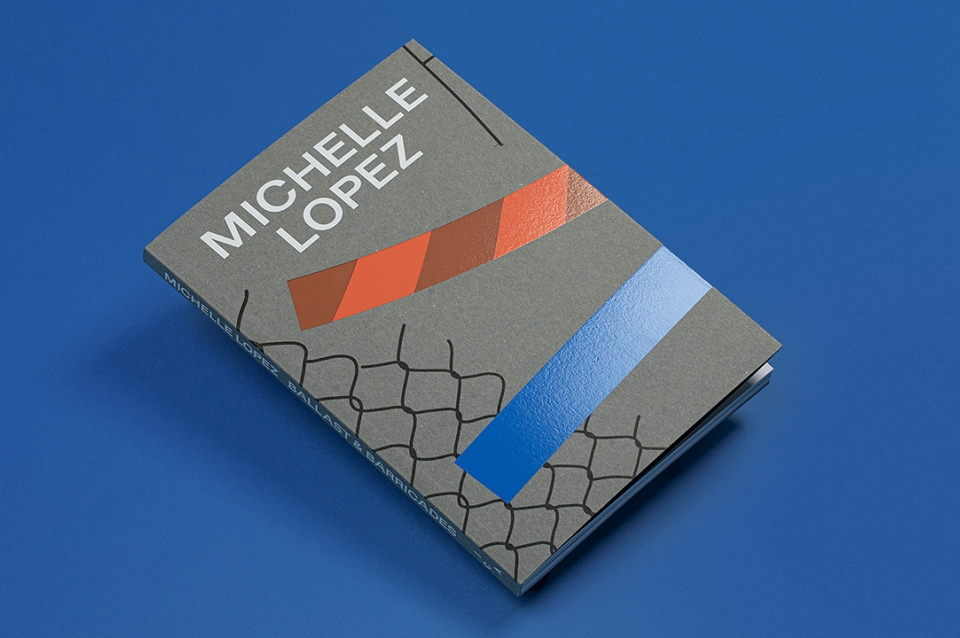

Penn’s Institute of Contemporary Art has published a catalog for Ballast & Barricades, the 2019-2020 exhibit by Michelle Lopez, assistant professor of fine arts. In this excerpt from her essay "Through the Barricades," Alex Klein, the Dorothy and Stephen R. Weber (CHE‘60) Curator at the ICA, gives context art historically and politically to the site-specific installation Lopez created. The publication, which was designed by Mark Owens, a lecturer in graphic design at Weitzman, is available from the ICA.

… Although Lopez relishes minimalism’s machined quality, its lack of figuration, and the conceptual parameters that allow others to fabricate the actual works following the artist’s instructions, she cannot help but question and be troubled by its assuredness of making, production, and authorship. For, as Lopez wrestles with her materials, she is also wrestling with a history of sculpture and its political contexts.

These concerns coalesce in her expansive exhibition Ballast & Barricades, which employs a formal, fragmented architectural language to critique symbols of nationalism, power, and consumption. In this site-responsive installation, Lopez brings together a selection of recent sculptures alongside a monumental intervention in the ICA gallery to create an architecturally scaled, suspended cityscape reduced to rubble. Blockades, borders, flags, and natural elements bleed together with remnants of construction sites and scaffolding that create a delicate system of counterweights and counterbalances—all meticulously crafted by hand. For Lopez, this sculptural terrain suggests an ongoing history of bodies and violence in the absence of figuration. It is an urban landscape fabricated out of the material remains of crisis, teetering on the brink of collapse, that is both playful and utterly terrifying.

In Ballast & Barricades, sculptural and political critiques merge. For example, the hand-warped wooden barricades, painted bright shades of NYPD blue and construction orange, literally bend the signifiers of authoritative boundaries and suggest alternative narratives of protest. But as they fly and twist through the installation they might equally remind us of objects frozen in the eye of a tornado, as they conjure diminutive riffs on forms such as Richard Serra’s imposing and controversial public sculpture Tilted Arc (1981–1989). In fact, Serra’s shadow appears often in Lopez’s work, from his steel monuments to his performative actions with lead—a potentially hazardous material that Lopez has frequently employed in delicate, yet biting works such as Flag (2014) and Throne II (2017), a prophetic nod to both the election of Donald Trump and to Alberto Giacometti’s Seated Woman (1949–1950).

…

Ballast & Barricades, [is thus] intended as a broader reflection on the balance of power through form as it extends into the world at large. In Lopez’s hands, the heft of Serra’s fabricated squares is transformed into an elegant, rhizomatic system of precariously perched, tendril-like, metal structures. These thin lines are held up by bright military-grade paracords—some with dangling, icicle-like glass shapes—and weighted down by rough hunks of street rubble collected from the rapidly gentrifying cityscape of the artist’s home in Philadelphia. To remove or push one element in the installation risks causing a catastrophic collapse that would bring the whole system crashing down. Similarly, during our own moment of upheaval in the US there is a renewed focus on crumbling bridges and roads, as if this real infrastructural breakdown mirrors the current political chaos. Lopez’s installation underscores that to be physically interdependent is also to be structurally intertwined.

…

Another way to situate Lopez’s work is through a trajectory that maps an alternative lineage of abstraction and the grid. We need only think of the healing arts of Emma Kunz; the pastel-hued canvases of Hilma af Klint; the color-block quilts of the women of Gee’s Bend; the wire-mesh sculptures of Ruth Asawa; or the methodical lines of Agnes Martin’s diagrammatic landscapes to begin to chart another path. In these “imperfect” or “bent” geometries, there is a kinship to be found with Lopez’s articulation of “failure,” as well as the connection of her rigorous physical feats to psychic experience. In turn, this recalls yet another important artistic reference point for Lopez in her mentor and teacher, Jackie Winsor, who she remembers evoking the importance of “dreams, shamans, gurus, and warrior strength.”(1)

…

This expanded definition of painting and drawing offers another entry point into sculpture that is rooted in the artist’s body, intuitive action, and material processes as opposed to the more didactic or prescriptive connotations associated with building, casting, construction, and fabrication. Winsor does not make her sculptures in multiple. Rather, she regards each work as an individual that is equally reliant on a combination of chance operations and her personal experience. This tension is evident in iconic works such as Burnt Piece (1977–78), Painted Piece (1979–80), and Exploded Piece (1980–82), in which she subjected her meticulously crafted and multilayered cube sculptures to the unpredictable aggressions of fire, dragging, and pyrotechnics. She recalls, “I wanted to bring together in the cube shape form and force, opposites in my reality at the time . . . and make them absolutely imbued with each other.”(2) This, of course, underscores that the biomorphism of the blob and the rigidity of Cartesian geometry need not be in total opposition. As Winsor has observed, a fishing net is also a grid.(3)

Perhaps the closest thing to this grid in Lopez’s dizzying Ballast & Barricades is the handmade chain-link fencing that punctuates the space, drooping and twisted. If for Winsor “form and force” are fused together in the body of the sculpture itself, for Lopez the absent figure is always implied in the spatial deployment of the markers and material residues of violence. In our contemporary moment, such architectures demarcate what Giorgio Agamben has called “spaces of exception,” all of those mechanisms of enclosure and control—cages, prisons, camps—through which state power acts on bodies in response to moments of crisis.(4) In Ballast & Barricades, Lopez turns these materials into a fragile lattice, simultaneously threatening and delicate, exploded and exploding. Just as she explores pathos in sculpture as a way of complicating masculinist narratives of artistic heroism, here Lopez allows us to see political power as itself constituted and constructed by forces that are at once totalizing and tenuous.

(1) From a conversation with Michelle Lopez on January 28, 2020.

(2) Excerpted from a public conversation between Michelle Lopez, Anna Sew Hoy, and Jackie Winsor on January 29, 2020, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania.

(3) Ibid.

(4) See Felicity D. Scott’s reading of Giorgio Agamben’s text “What Is a Camp?” referenced in Outlaw Territories: Environments of Insecurity/Architectures of Counterinsurgency (New York: Zone Books, 2016).

Expand Image

Expand Image