August 30, 2024

Alternative Landscapes

For students in Sean Burkholder’s landscape architecture studios, comics are a vehicle for deeply-researched responses to environmental urgencies.

By Jared Brey

Close

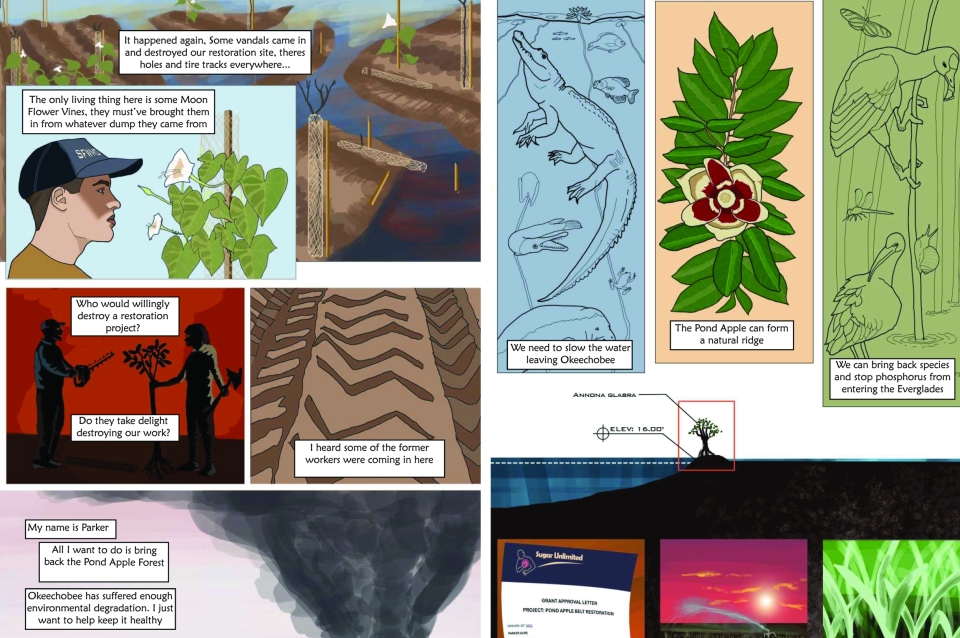

Work by Keith Scheideler and Gunay Mmadova

Work by Maura McDaniel

Work by Nina Lehrecke

Work by Caroline Schoeller

“We still want the future to be better than the present,” Burkholder says, “But if you put people in a different present, they’ll imagine a different future collectively. (Photo Caroline Schoeller (MLA’24)

View Slideshow

View Slideshow