November 14, 2024

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Tags

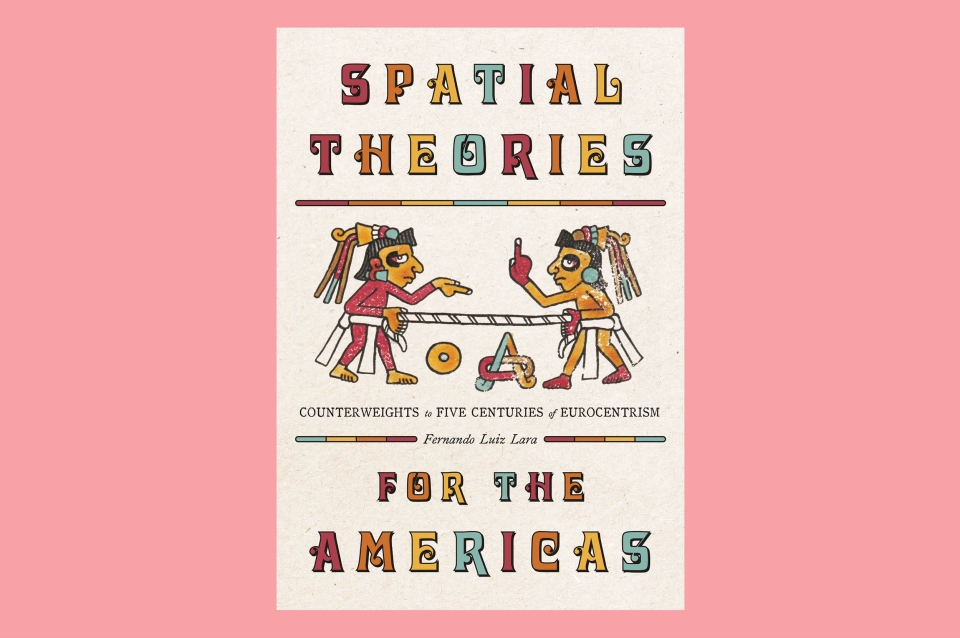

What role did pre-Columbian American ideas around the built environment play in shaping European modern thought? In the new book Spatial Theories for the Americas: Counterweights to Five Centuries of Eurocentrism, Professor of Architecture Fernando Luiz Lara argues that the study of architecture, including the history of the Americas, has overwhelmingly been seen from the vantage point of writers from Europe. Lara urges us to examine the American built environment from a new perspective built on decolonial theory, rather than the long history of Eurocentric writing, and consider how ideas around places and spaces that originated in the Americas have been articulated. In this excerpt from the introduction, Lara describes the structure of the book, which expansively takes in the Americas, from Canada to South America, and moves from pre-Columbian times to the present day.

This book is not about the ancient history of the Americas like the one written by Paulette Steeves (1), nor a survey of our American built environment like the one written by Clare Cardinal-Pett (2). What I hope to do here is to draw from multiple sources that have advanced the knowledge of our American history, discuss the role of architectural theories in the erasure and exclusion that happened after 1492 (in the first part of the book), and start compiling theories and concepts that connect to and learn from our history (in the second part). I am aware that the scope of the book is quite ambitious, and to that criticism I would answer that I am just a storyteller, connecting the dots that I see as shiny new points of light elaborated by hundreds of other scholars, trying to show you a new constellation. Let’s call this exercise an attempt at theorizing because to me it is clear that our American spaces have been undertheorized. The measure of my success would be the opportunity given to other scholars to use those stories as roadmaps for their investigations. The measure of my failure would be if I elicit no response at all, like so many scholars from the so-called “global south,” ignored and relegated to footnotes.

At this point, I need to elucidate what I mean by architectural theories. Following K. Michael Hays proposal of theory as a practice of mediation between building form and its social-economic context (3), I intend to use the spatial experience of the Americas as a thread to both measure and connect the dots of multiple data points in the history of our continent. Not coincidentally, the Mixtec sign for “architect” depicts two men stretching a thread, measuring something (4). My proposal here is to propose and discuss a set of concepts that will, eventually, develop better lenses to analyze the built environment of the Americas.

The first part of the book, entitled “Dismantling Eurocentrism” is comprised of four chapters. The first one is an analysis of the disappearance of the Americas from canonical books of architectural history until the late 20th century, starting from the Banister Fletcher editions of 1896, 1903, and 1919, to Mumford of 1935, Benevolo of 1972, and Kostof of 1985, among others that deal with the European Renaissance and the rise of architecture as we know it in the 16th century. The first chapter closes with a discussion of the improvements and the limitations as presented by the survey books of the 21st century: James-Chakraborty of 2014, Jarzombek, Prakash, and Ching of 2017, and Ingersoll of 2018. Chapter 2 focuses on the changes around spatial representation that happened as a consequence of European expansionism and the occupation of the Americas in the 16th century, leading to the Cartesian synthesis of Cogito Ergo Sum of 1637. The third chapter continues the discussion of the Cartesian revolution with an analysis of its American roots, from Montaigne’s conversation with the Tupinambá in 1562 to Antonio Rubio‘s “Logica Mexicana” of 1603.

Chapter 4 closes the first part with a proposition that many of my colleagues will consider heresy, but that I am happy to defend. I depart from Setha Low’s discussion of the Mexican Zocalo as the template for Plaza Mayor in Madrid, designed by Juan de Herrera for King Felipe II in 1581. From there, I present the open chapels built in 16th-century Mexico to elaborate on the question of how much the open spaces of absolutist Europe were influenced by the open spaces of the Americas. My point is that majestic open spaces and elaborate axis, the core of the so-called urban baroque of the 17th century, were a hegemonic feature of indigenous Americas and we need to add that precedent to our discussions around the Baroque, a spatial concept developed by the Jesuits on both sides of the Atlantic.

The second part of the book, which I titled “Spatial Theories for the Americas” is comprised of seven chapters, organized chronologically, to present actors, concepts, and theories that I consider fundamental to understanding the spaces of the Americas. In Chapter 5, I depart from Viveiros de Castro’s Amerindian Perspectivism to propose that we need to incorporate relational knowledges in our design pedagogy and practice. The sixth chapter is a discussion of the colonial strategies of occupation, with a debate around the presence of the orthogonal grid thousands of years before Columbus's landfall and the implications of the grid as a tool for exclusion first as seen in the Spanish settlements, and later as a tool for erasure when Thomas Jefferson expanded the grid to continental scale.

Chapter 7 introduces Chicago as a fundamental place to understand the 19th century in the Americas, from the exponential growth between the 1830s and 1890s to the first suburbs, the Columbian Exhibition of 1893, and the racialized skyscrapers of the turn of the century. Here, I juxtapose Chicago’s development as the northern way, based on transportation strategies, to the reforms of downtown Rio, Mexico City, and Buenos Aires that epitomize the southern way of segregation with much less physical distance. The eighth chapter juxtaposes Frank Lloyd Wright, Juan O’Gorman, and Lucio Costa, not only to illuminate their central ideas of land, economy, and history but to discuss their deafening silence around the racial issue and the participation of regular people in their ideas of modernity. Here, I highlight a wide gap opening between what architects were proposing and what intellectuals were discussing, because the same population that was missing from Wright, O’Gorman, and Costa, occupied a central position in the thoughts of Jose Vasconcellos, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Mario de Andrade, among so many others.

In the ninth chapter, I discuss American responses against the hegemonic modernism of the first half of the 20th century, departing from Catherine Bauer and Carmen Portinho, socially conscious but still defending modernist ideas, following up with a discussion of how Eurocentric the mid-century reaction to modernism was, as epitomized by Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction. In opposition to Venturi, I argue in the second third of Chapter 9 that Jane Jacobs and Denise Scott-Brown are the authors who better understood North American spaces in the second half of the 20th century. The last third of the ninth chapter is devoted to my previous research on Popular Modernism as a phenomenon that creates tensions and problematizes Venturi, Jacobs, and Scott-Brown. If the ninth chapter was heavily geared towards the north of the Americas, the tenth strikes a balance by focusing on theories from the south. I argue in Chapter 10 that Paulo Freire, Liberation Theology, and CEPAL are important contributions to the study and the production of our American spaces. Moreover, the very decolonial theories that I use as a basis for this entire book are very much a result of CEPAL where Anibal Quijano and Pablo Casanova worked for years, added to the fact that Enrique Dussel's thoughts are directly linked to Liberation Theology. If anything, it is Paulo Freire, the one still not accepted by architectural scholarship despite him being recognized as a major theoretician of the 20th century, the only one from the global south to be amongst the 20 most cited scholars of all time. The emphasis on the south continues in the eleventh and last chapter of the book, in which I discuss the structures built without architects and mostly without the use of drawings and reject the label of “informal” commonly applied to them. As I explain in Chapter 11, every building has form and by calling some “informal” we are denying the agency and the intentions of its builders. Instead, we should understand favelas and barriadas as territories of resistance, afro-indigenous spaces that can teach us how to decolonize for real, not as an intellectual metaphor.

This book is a call for my fellow designers and scholars of the built environment to add their stories of resistance, empathy, and relational knowledges to the fight to build a better America, or in the words of Ailton Krenak, delay the end of the world.

1) Steeves, Paulette F. C. The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere, n.d.

2) Cardinal-Pett, Clare. A History of Architecture and Urbanism in the Americas. 1 edition. New York: Routledge, 2016.

3) Hays, K. Michael. Architecture Theory since 1968 / Edited by K. Michael Hays. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1998: 10.

4) Folio 22 of codex Vindobonensis, Staatsbibliotheck, Vienna. Available online.

Expand Image

Expand Image