December 2, 2025

Penn Team Honored with Charles E Peterson Prize for Work on Nakashima House

By Cassandra Dixon

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

In April 1946, just south of the small town of New Hope, PA, George Nakashima began to build a home for his family. As he poured concrete and dug the foundation, his wife Marion and daughter Mira lived with him in an army tent on a hilly field. The second building on his land, the only thing which had come first was a woodworking studio. The campus in New Hope would grow to be more than a dozen buildings, where Nakashima would spend decades working and solidifying his legacy as an iconic woodworker, furniture designer, and architect of the 20th century. When he passed away in 1990, the home he built carried on the distinct blend of modernism and craftmanship that defined his artistic vision. Mira Nakashima, a designer and architect herself, has stewarded her father’s legacy into the 21st century through her work with the Nakashima Foundation for Peace. Her advocacy has inspired partners with their own rich history.

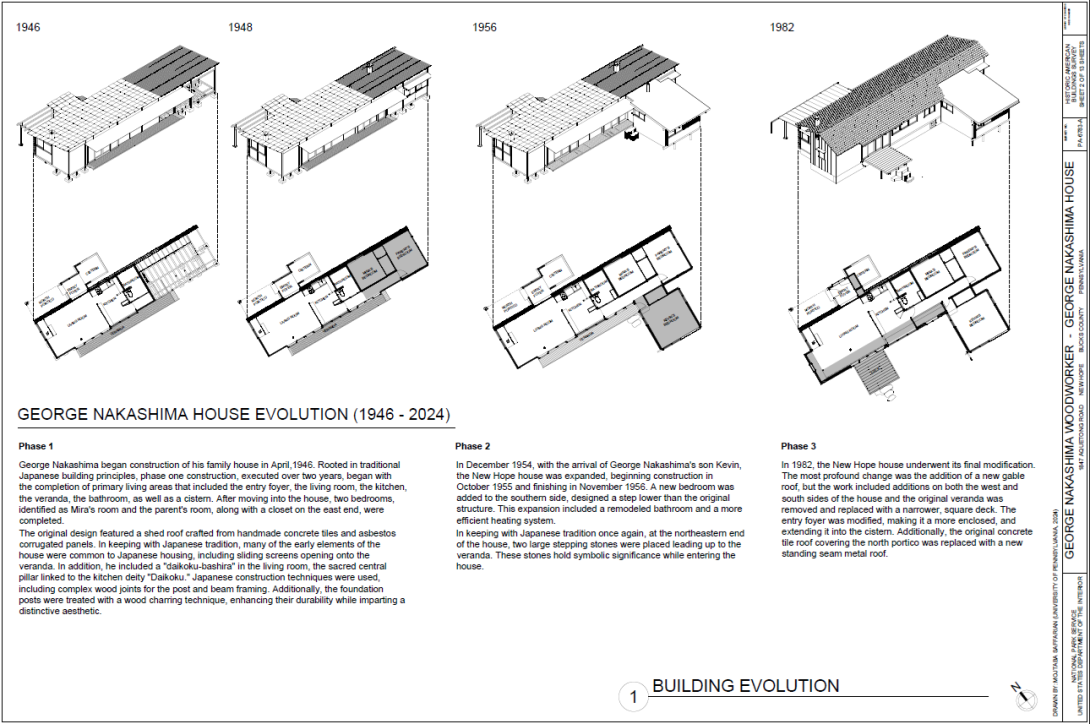

Documentation from the HABS report of the evolution of the Nakashima family home.

In 1933, a thousand unemployed architects, drafters, and artists would find work through a seminal program, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS). Proposed by Charles E Peterson, the HABS was a New Deal project that would implement “for the first time the comprehensive examination of historic architecture on a national scale and to uniform standards.” This survey collects drawings, photographs, and historical reports of American buildings ranging from the Golden Gate bridge to one room schoolhouses. Now, Peterson is remembered through the prestigious juried award which shares his name. Given to students who have produced a set of measured drawings “that makes a substantial contribution to the understanding of the significance of the building, structure, or cultural landscape,” it recognizes an ongoing commitment to service and preservation as Peterson advocated. The prize is given as a collaboration of the National Park Service Heritage Documentation Programs, the Philadelphia Atheneum, American Institute of Architects, and the Association for Preservation Technology International. The drawings completed by the winning students will become part of the permanent HABS archive of thousands of American buildings. With extensive documentation from a team at the University of Pennsylvania, amongst those buildings is the family home and studio which George Nakashima built on a hill in New Hope, PA.

“The George Nakashima House first entered my work as a case study for my thesis, in which I examined the role of BIM in historic preservation and, using Revit, explored how its tools can embed multiple layers of data within a single architectural element, allowing it to serve both as a database and as a medium for graphic expression,” Penn historic preservation alumnus Mojtaba Saffarian (MSHP’24) explains. After his thesis was completed, Saffarian continued to work on documenting the site with a team from the Department of Historic Preservation’s Center for Architectural Conservation (CAC) guided by Professor John Hinchman. The house was a unique site for the technique, Hinchman explains, because it was “smaller and more intimate than our previous projects, allowed us to spend more time on the details, which can be more challenging to capture accurately with scanner data," such as the philosophy of the house architecture, evolution sequence, and its concealed structure. Hinchman says that the house really highlighted the unique nature of Nakashima’s design. The project “helped cement in my mind how profoundly modernist architecture was shaped by traditional Japanese aesthetics, with the open floor plan, the use of natural materials, as well as the post-and-beam construction” he notes.

"Since the drawing sets will be preserved in the archives at the Library of Congress, we wanted to produce something that was detailed enough to meet technical requirements but also would be interesting and legible to those without specialized training."

Hinchman and Saffarian’s work was headed by Professor Frank Matero as project director and relied on the research of William Whitaker, Michael Henry, Wendy Jessup, and Paridhi Goel. Together, they created measured drawing sets of the home to donate to the Heritage Documentation Programs, including HABS. Since the drawing sets will be preserved in the archives at the Library of Congress, Saffarian said they wanted to produce something that was detailed enough to meet technical requirements but also would be interesting and legible to those without specialized training. HABS understands documentation as “an alternative means of preservation…a primary tool for the stewardship of historic structures, whether for day-to-day care or as protection from catastrophic loss.” The drawings which the Penn team have completed are part of that legacy of stewardship, and the Nakashima house is an essential candidate for that preservation.

Even though Nakashima designed and built the house himself, there are not consistent records of his process. When he remodeled the home in the early 1980s, he simply drafted over his original documents from 1946. For both scholarly work and ongoing preservation it was essential to understand the journey Nakashima undertook when building the home, as well as the engineering and design. The extensive documentation created through this project makes that possible. Earlier this year, the team won a Grand Jury Award from the Preservation Alliance of Philadelphia. Now, the work the CAC team completed at the George Nakashima house has been honored with the Charles E Peterson prize. This is the first time a team from Penn has won this award.

“These, I believe, exemplify good preservation drawings,” Hinchman says. “More akin to infographics than traditional architectural drawings, many of the sheets convey—through the use of color, 3D renderings, and photography—the complexity of the Nakashima house.”

The work honored by the Peterson prize was only part of the work done by the Penn team. They also produced a second set of complimentary documents which Saffarian explains show “the house’s evolution, construction methods, and context through a combination of drawings, 3D models, texts, diagrams, and images.” The second set that the team produced not only provided the record necessary to continue the stewardship and maintenance of the property, but also the ability to see the development of the house over time. “These, I believe, exemplify good preservation drawings,” Hinchman says. “More akin to infographics than traditional architectural drawings, many of the sheets convey—through the use of color, 3D renderings, and photography—the complexity of the Nakashima house.” The second set of drawings, paired with a detailed historical report from Penn archivist William Whitaker, create a view of the site across time. They have made it possible to watch Nakashima build his family home once again.

This is part of an ongoing relationship between the Nakashima Foundation for Peace and Penn. Amongst other work, previous collaborations include a preservation plan, a summer capstone studio that studied the feasibility of a visitor center, and a carbon and energy assessment.