March 9, 2022

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Tags

Media Contact

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

Last summer, David Leatherbarrow achieved the rank of professor emeritus and began a new chapter in a career at Penn that began in 1984. Over the last 38 years, Leatherbarrow has produced a vast body of written work on the history and theory of architecture and gardens. He’s also taught hundreds of students at Penn and Cambridge and reached still more as a guest speaker at colleges and universities around the world, earning the 2020 AIA/ASCA Topaz Medallion in Architectural Education from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA). On March 31, Weitzman will host a lecture and reception in Leatherbarrow’s honor with Irish architect John Tuomey, and on May 20, colleagues and former students will gather for a program of lectures and written pieces that will be compiled into a book in Leatherbarrow’s honor.

In an interview, Leatherbarrow talked about the ideas that have sustained his attention over time, how Penn students differ from others, and why Philadelphia is the best city to study architecture.

You once wrote, “Criticism verbalizes architecture.” How do architectural theory and criticism play a role in culture and the perception of architecture?

I think there’s criticism in both theory and practice. No project begins without criticism. One can be critical of the location, the way the buildings and the streets are laid out, the ways they’ve been constructed. But I believe there’s also an architect’s criticism of his or her own work; I guess you could call that “self-criticism.” And thirdly is what I’d call “non-professional criticism.” Everybody has an opinion about what’s good or bad in their apartment, their house, their street, their neighborhood. In a sense we’re all critics. But the professor or the author’ss criticism is better informed, and when articulated, perhaps more consistent and clear. I think these sorts of criticism relate to one another but can be distinguished. I think they are internal to practice but also outside of it. I see them as a necessary dimension to professional understanding.

And you see buildings as embodying architectural criticism.

I think so. Buildings are critical of what’s preceded them. A simple point I’ve often made to students over the years is that if there’s nothing wrong with a location, there’s very little for you to do. Buildings often critique what preceded them and propose a better way of acknowledging the desires and practices of contemporary life. There is verbal criticism, written and oral, but also built and visualized critiques of the environment we’ve inherited. That gives architecture its task—a response to that criticism.

What made you want to investigate topography as a common premise for architecture and landscape architecture?

When I was chair of the architecture department at Penn, I explained to my colleagues and students that I have a basic attitude toward the field: In short, architecture is always built somewhere. That little phrase, as obvious and even pedestrian as it is, points to a very creative tension between architectural technology and architectural topography. In our 20th and 21st centuries, we’ve been very good with technology, building things in smarter and more efficient ways. We haven’t been quite so good in our understandings of topography—how buildings are a part of their site, part of the landscape or cityscape, and part of the wider environment. I’ve always felt a need to understand the work as a way of structuring a dialogue between the part and the whole.

Years ago, my PhD addressed the siting of buildings and gardens. My first course at Penn in 1984 was on architecture in the urban context. My recent books, 30 or 40 years later, look at buildings in the landscape, and now, more recently, the ecological environment. There’s a sociopolitical side to this. In the United States, we are very confident about the importance of every person’s identity and individual rights. We’re not so good at recognizing what we share. My approach to this issue of the individual and the collective is through architecture. And I ask, I’ve asked for years, what the individual work necessarily shares with—how can it contribute to—the wider landscape. The general thesis is that engagement, involvement, and mutuality of contributions will make a better living environment.

"I’ve continually refocused on the involvement, participation, or mutuality of contributions that single buildings and design make to the environment."

Do you feel like the field of architectural theory, history, and criticism has pushed in that direction with you?

I don’t think there’s an architectural theorist or an architect today who can escape or ignore the expectation for rethinking how the discrete work participates in the broader environment. Maybe 20 or 30 years ago architects could say, “I’ll just occupy myself with my building, the way it looks, the way it utilizes this or that material.” We don’t have that option anymore. That style of thinking is gone. I would never say that I was prescient, but for these decades, I’ve continually refocused on the involvement, participation, or mutuality of contributions that single buildings and design make to the environment.

Sometimes contributions from neighboring fields have overshadowed an architects’ understanding of the discipline itself. The concepts, language, skills, traditions that we call architecture have been thrown into shadow by stunning and important insights from anthropology, from art, or other cognate fields. And, in other periods, there’s been a desire among critics and architects to recover, to remember disciplinary knowledge. But sometimes preoccupation with the field itself becomes insular, and arguments in favor of what was in the 1990s called architectural autonomy can lead to a higher degree of abstraction, verging on indifference. In my sense, the preferred alternative is pretty simple. Neither extreme—architecture as a subset of another field or architecture as wholly independent—neither of those extremes make any sense.

Over the years, and no doubt in the future, there will always be an expectation of theory and criticism to be applicable, that the real test of a theory is its consequence in the built environment. It’s an understandable desire. However, I think what’s happening there is a transformation of a way of knowing the world into a way of transforming it, as if theoretical were no different from technical knowledge. I know there must be a relationship between understanding and acting, reflecting and designing, but I think that relationship is indirect, not this idea will lead to that outcome.

So there’s been a tendency to evaluate an architectural theory based on how well you can operationalize it in practice?

Exactly that. We all want results. But sometimes we want them too immediately and you end up abbreviating the understanding. That’s what I’m sensitive to.

You were in England before you were at Penn. How have your students’ interests evolved over the years?

I went to England on a Fulbright scholarship and I was meant to stay nine months. The fellowship was renewed for a second year and what was intended to be nine months became seven-and-a-half years, a PhD that I never really intended, and the beginnings of a career in teaching. My wife and I decided we should give the US a try before we settled in England. So we came to Philadelphia on the invitation of then-chair Adèle Santos. On the phone I said, “What’s happening at Penn? Kahn died. Is there anything of interest there?” She said, “I’m rebuilding the program, and I want some young people to come and help me create a new program.” I went and met professors Marco Frascari, Richard Wesley, a few other young people, and she gave us the freedom to basically reconceive the core curriculum for both theory and design, which was fantastically exciting.

The students were very different. My Cambridge students were very articulate but very hesitant to draw. They wanted to think their way through problems, and they did so very impressively. When I came to Penn, there was far less interest in history and the cultural implications of a project. Students wanted to act, to do things. They felt that problems in our society needed to be addressed through architectural means. And they also felt a strong desire to make things, to create things, and thus had a double interest in serving society and expressing their own sense of what’s beautiful and what would make a nice environment. So I found myself in an extremely interesting, productive, and engaging environment. I found it very different but very attractive. So I came in 1984 to stay for three months and it became 38 years.

Do you think Philadelphia is a particularly productive place to think about architecture?

I’m admittedly dogmatic about this. I don’t think there’s anywhere that’s better than Philadelphia. It’s a fantastic city to study architecture, given the makeup of its population, its rich and wonderful diversity, its history, the built fabric, its cultural institutions, the spectacular topography with a river running through it and the great Fairmount Park. There are so many instructive examples at the level of built work, natural environment, cultural background and at the same time pressing problems. Nobody is particularly happy with all that we have here, and yet we have a lot. There’s a lot to work with and to transform, to understand and then modify. It’s a really great place to study architecture and I must say, in the US, I’m not sure I’d prefer to be anywhere else.

What do you hope people continue to read of your work as you retire? Or how do you hope your work at Penn is seeded into the program?

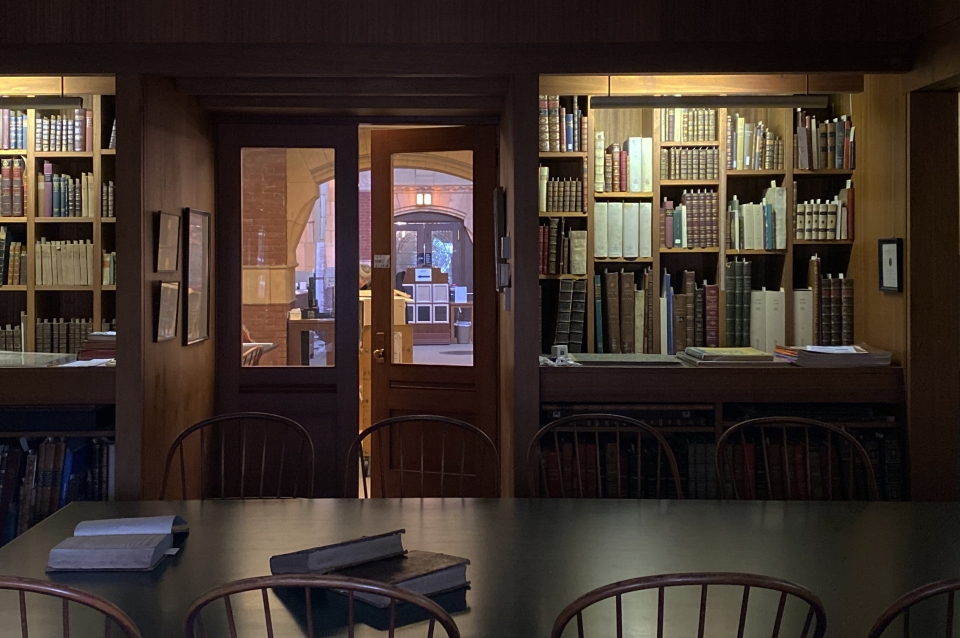

Ours is a very literate culture. Our students are very smart and very literate. We can all read books. It’s not so easy for people today to read buildings. Let’s say a person comes today to the Penn campus and is directed toward one of the great buildings, the Fisher Fine Arts Library. Everybody can read what’s written on the windows, it’s like a book, and you can see what the designer had in mind when thinking about a library. But it’s not so easy for people who are not trained in architecture to stand outside the Fisher Fine Arts building and understand the distribution of spaces, to understand their sequence—this, then that—and what it means for individual and shared learning, memory, and so on. In other words, not so many people can read buildings the way they read writing.

I hope those who pick up what I’ve done will see how it’s possible to do a close reading of a built work. It has something to say. Insofar as a comparison with writing is possible, a built work is also legible. It has a story to tell. And I think built works, if one takes the time to look at them, can tell us about where we are in the world, and can tell us our histories. They embody, and through that embodiment, they narrate cultural content. And I hope that if someone picks up something that I’ve written maybe it will show how the world can be read through its buildings. I hope something of that is communicated through what I’ve done.

Expand Image

Expand Image