Why Rental Support Works

Cash assistance drastically reduces tenants’ likelihood of eviction and homelessness, according to an ongoing study of the PHLHousing+ program from Weitzman’s Vincent Reina and Sara Jaffee of Penn Arts & Sciences.

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Cash assistance drastically reduces tenants’ likelihood of eviction and homelessness, according to an ongoing study of the PHLHousing+ program from Weitzman’s Vincent Reina and Sara Jaffee of Penn Arts & Sciences.

“You’re seeing a dramatic improvement in housing stability outcomes,” says Reina. He was photographed with Sara Jaffee at the Fisher Fine Arts Library on October 3. (Photo Eric Sucar)

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

What happens when you give small monthly cash payments to low-income tenants in unstable housing situations?

For one thing, you dramatically reduce their chances of getting evicted or experiencing homelessness. That’s according to the first findings from a two-and-a-half-year study of a cash-assistance program in Philadelphia from a team of researchers led by Vincent Reina, a professor and associate chair in the Department of City and Regional Planning, and Sara Jaffee, Class of 1965 Term Professor and chair of the Department of Psychology at Penn Arts & Sciences.

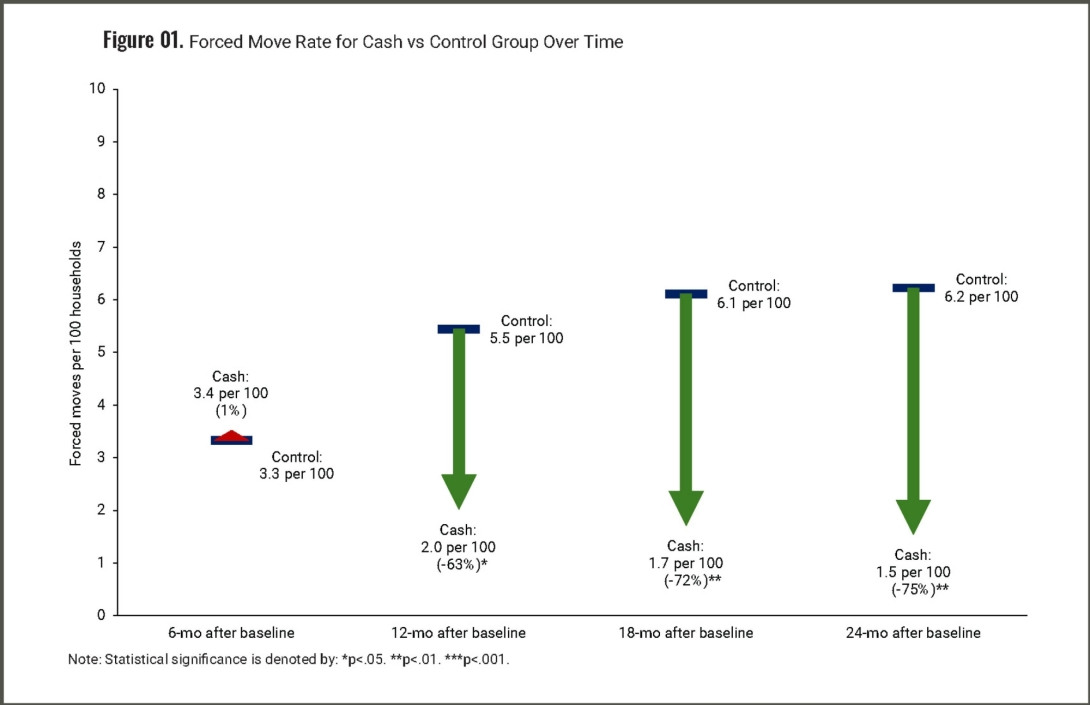

The study showed that tenants who received a monthly cash payment from the PHLHousing+ program, calculated to offset rents they struggle to pay, were up to 75 percent less likely to be evicted than tenants with similar incomes who didn’t receive the benefits. They also were less than half as likely to experience homelessness, and, after two years enrolled in the program, were 22 percent less likely to report serious concerns with housing quality.

“In this completely unrestricted form of rental assistance,” says Reina, founding director of the Housing Initiative at Penn, a research unit based at Weitzman, “you’re seeing a dramatic improvement in housing stability outcomes.” The findings are directly relevant to policymaking, Jaffee adds. “We hoped that a program that reduces housing cost burdens would reduce rates of forced moves and homelessness, but those rates dropped substantially,” she says. “I’m impressed by the size of the impact."

PHLHousing+ is a cash assistance initiative designed to help vulnerable tenants in Philadelphia pay their rent with as few obstacles as possible. Reina pitched the program to city officials more than half a decade ago, when policymakers around the country were eagerly looking for solutions to a growing eviction crisis. The benefit was to be coupled with a research component—the first randomized control trial of its kind to examine the efficacy of various housing assistance programs.

In the biannual survey, participants were asked, “How many times have you been evicted from your home in the past 6 months?” The study team used this information to calculate the forced move prevalence per 100 households.

Former Mayor Jim Kenney announced the program in March 2020, a little more than a week before the COVID-19 shutdowns began. The program was sidelined as the city and the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation (PHDC), along with cities around the country, turned their attention to emergency rental assistance for people affected by the pandemic. But after receiving support from local foundations and the city committing some local funding, it was up and running.

From the beginning, Reina worked with PHDC to design the program and evaluate its effect on tenants through his Stoneleigh Foundation fellowship. It was a unique chance for Reina, who researches housing policy and assistance programs, to create a pilot that tests a new approach to rental assistance, in partnership with the agencies administering it. Given that the program was designed to target families with children, with the theory it would have downstream benefits, Reina sought to bring in a scholar with expertise in developmental psychology. Soon Jaffee became a partner across all aspects of the project and has since co-authored the findings report released in August of 2025.

Director of the Risk and Resilience Lab at Penn, Jaffee studies how early adverse experiences in life shape the development of individuals, families, and communities, with a focus on violence and mental health. Researchers are increasingly understanding eviction and homelessness as traumatic occurrences, especially for young people.

Jaffee and Reina are working together to assess how rental assistance programs can influence life outcomes beyond housing stability, including social and emotional development and behavioral health. The ongoing study will probe data on family well-being, with questions about children’s feelings of depression and anxiety, rule-breaking and aggressive behaviors, and ability to sit still and concentrate. Other aspects of the study will examine the benefit’s effect on household mobility, neighborhood access, financial stability, and other outcomes.

Before getting that granular, though, Jaffee says it was important to determine whether cash assistance does, in fact, help people stay in their homes. “The rest of it is really premised on whether that piece worked,” she adds. “All our theories of change have to do with the ways in which these programs promote housing stability and better housing quality, and thereby make some of these other things possible.”

“Rental assistance works. It genuinely improves people’s housing in very obvious and demonstrable ways.”

The initial study phase has included surveying three groups of people about their housing circumstances over time. One subset of 301 tenants received cash assistance—$881 a month on average—through the PHLHousing+ program. They were selected from the bottom half of the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s waitlist for Housing Choice Vouchers, the biggest housing assistance program in the United States, which helps cover the gap between recipients’ incomes and rent. Another 170 tenants received those vouchers. A third control group of 700 people received no assistance. All survey respondents, regardless of group, received small cash payments for their time.

Reina, Jaffee, and colleagues also conducted semi-structured interviews with tenants in each of the three groups, asking about recent moves, ability to pay rent, housing conditions, and family life. The groups had similar demographics, including mostly unmarried Black women with one or two children. Most had received a high school diploma or higher and were working full- or part-time. Their stories, however, were wildly divergent, says Stefan Hatch an urban studies major who began working on this project when he was a first-year student.

Initially, he says, the interviews were more rigid and stuck to a list of questions, but over time he developed a natural rapport with many of the subjects and the conversations became less formal and more fluid. The qualitative interviews reinforced the study’s conclusions. “People with not that much money tend to know how to budget and how to manage their cash,” Hatch says. “There’s this perception that people can’t do that.”

PHLHousing+ is a cash assistance initiative designed to help vulnerable tenants in Philadelphia pay their rent with as few obstacles as possible. (Photo iStock/Chris Boswell)

Unlike Housing Choice Vouchers, cash assistance is unrestricted; in other words, recipients don’t have to spend it on housing. And in the PHLHousing+ program, which distributes benefits on a dedicated debit card, there’s no clear way to track exactly how they do spend it. That wasn’t the point, according to Matthew Fowle, research director at the Housing Initiative at Penn and co-author on the project. Making it easy to use was.

While Housing Choice Vouchers help more than 2.3 million families in the US afford monthly rent, millions more qualify for vouchers but don’t receive one. And 40 percent of tenants who do actually get one have trouble using it, for a variety of reasons, including landlords refusing to accept vouchers—a type of discrimination that’s increasingly a target of state and local law—and a general shortage of housing available at rents and quality that meet the program’s eligibility guidelines. Vouchers also have to be used within a certain amount of time, sometimes in as little as 60 days.

In the Philadelphia study, a quarter of the tenants in the voucher group couldn’t use them. For those who did, it took an average of 110 days—almost four months. By contrast, all cash recipients utilized the benefit, and in just 21 days, on average.

“We know that it’s getting used for housing because we’re seeing these huge drops in eviction and homelessness,” says Rachel Mulbry, director of policy and strategic initiatives at PHDC. “If it weren’t being used for housing, we would expect to see eviction rates and experiences of homelessness stay about the same.”

The research team says this work overall and the first set of results provide critical data for policymakers seeking to address these housing crises in the U.S. “The idea of this program is to provide cash with no strings attached straight to the tenant, rather than a traditional benefit, which would go through the landlord,” Fowle says. “Our study shows that regardless of whether you give people cash or a voucher, rental assistance works. It genuinely improves people’s housing in very obvious and demonstrable ways.”

The program is currently funded through mid-2026. The Housing Initiative at Penn and the Risk and Resilience Lab continue to survey tenants in each of the three groups, with plans to publish more findings on housing, behavioral and developmental outcomes next year.

In the meantime, program leaders and the researchers both say the data show PHLHousing+ is doing what it was meant to do. “When we invest in people,” Mulbry says, “their lives get better.”