February 21, 2024

At Shenandoah National Park, the Past, Present, and Future of a Historic Center of Black Life Come into Focus

By Matt Shaw

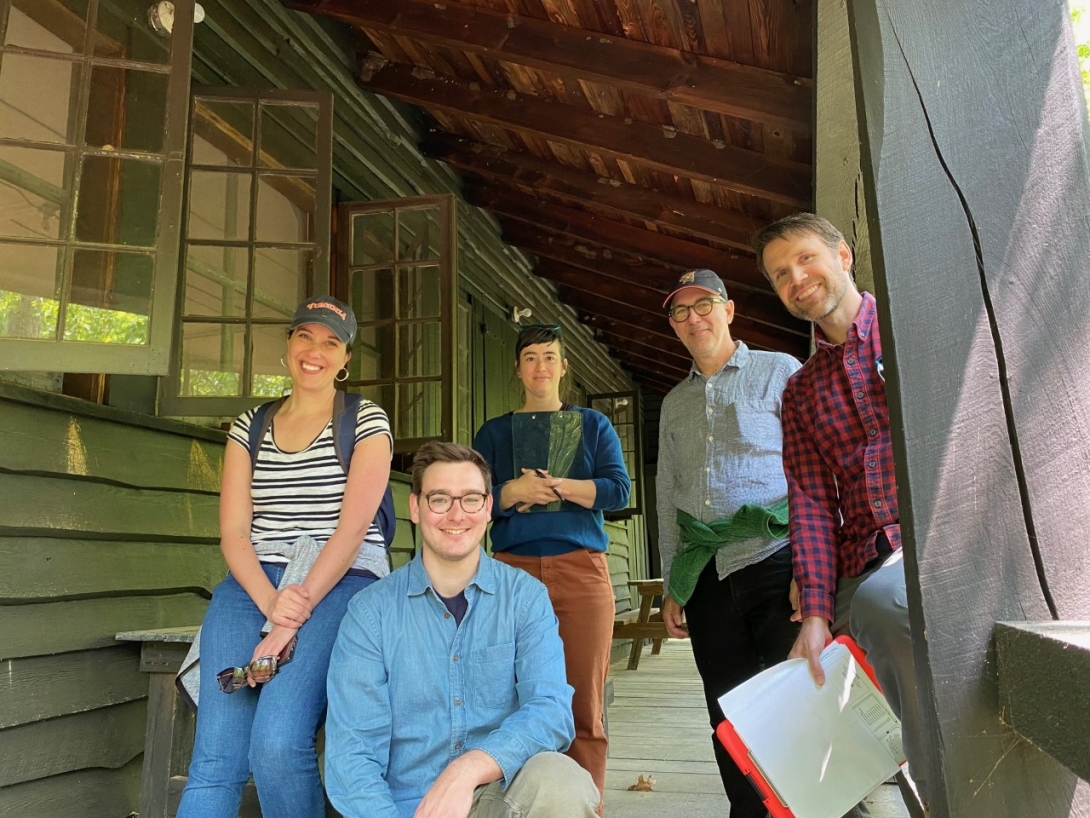

Today, Lewis Mountain remains little changed from when it was built in the 1930s and 1940s. It retains all of its rustic cabins and its central lodge. (Photo: Jacob Torkelson 2022)

Expand Image

Expand Image