March 6, 2025

Penn’s PhD in Architecture and the Echoes of History

By Matt Shaw

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Michael Grant

mrgrant@design.upenn.edu

215.898.2539

Franca Trubiano’s office in Meyerson Hall overlooks the legendary Frank Furness–designed Fisher Fine Arts Library, where many spirits of what is now the Weitzman School of Design’s history dwell. With this legendary view behind her, she reflects on the enduring six-decade legacy of the PhD program in Architecture at Penn, which she directs. As an alum of the program (PhD’05), and now associate professor of architecture and chair of the Graduate Group of Architecture, she knows the story intimately.

Penn’s PhD program celebrates its 60th birthday in Academic Year 2024-2025, making it the oldest in the US. On March 21, the program will host a day-long public event, titled Resources, Resilience, and Resistance—60 years of Advanced Architectural Scholarship and Research at Penn. The gathering of students, alumni, faculty, and invited guests was conceived to highlight the breadth of influence the program has had, and outline many of its success stories. “We now have 237 graduates strong, located around the world, teaching at leading schools of architecture; we are a truly global community,” Trubiano says.

Storied History, Distinguished Graduates

The PhD program was founded at what was then the Graduate School of Fine Arts in 1964 by G. Holmes Perkins. His former office, now the Fisher Fine Arts Library Rare Book Room, holds many books from his own collection and has served generations of Penn scholars. Perkins set the course of the GSFA with a unique marriage of theory and practice. As dean, particular attention was given to the discipline’s history and the philosophy of technology. Perkins had been at the Harvard Graduate School of Design during the arrival of Walter Gropius. When in 1959 he was hired as the school’s dean, he founded the Landscape and City Planning departments and instituted the Bauhaus-inflected pedagogy of total design at Penn, he elevated the role of art and science in the curriculum and replaced the Beaux-Arts model with an emphasis on cross-disciplinary thinking, one that defines both Weitzman and the PhD program today.

Perkins invigorated the school with new ideas as well as new people who helped define the culture in the post-war period. He hired luminaries including Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi, Ian McHarg, Denise Scott Brown, and Blanche Lemco van Ginkel, the prominent Canadian planner and educator. In 1975, Anne Tyng, colleague and key member of Kahn’s office, was one of the first women to receive a PhD in architecture at Penn. In 1976, Turkish emigré, former political prisoner and filmmaker Feride C̣ic̣ekoğlu Oymak was the second woman to receive a PhD.

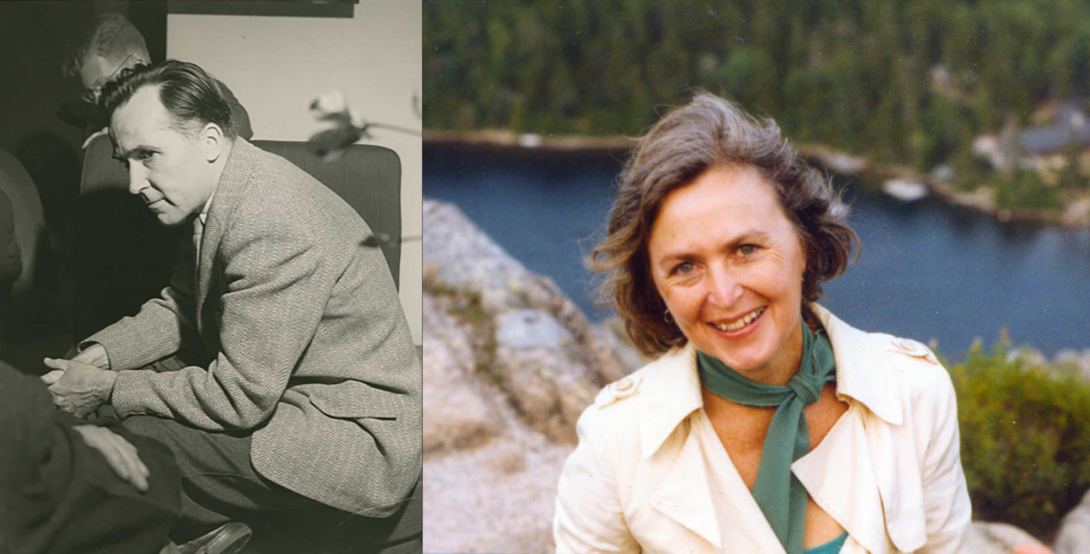

G. Holmes Perkins (Image: G. Holmes Perkins Collection, Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania); Anne Tyng in 1978 (Image: Anne Tyng Collection, Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania)

Following Perkins’s retirement from the PhD Program in 1983, the program has had several graduate group chairs including Peter McCleary (1983-1987), Joseph Rykwert (1988-1992), Marco Frascari (1993-1997), David Leatherbarrow (1998-2019), Daniel Barber (2020-2021), and, since 2021, Trubiano—herself a graduate of the program.

Peter Laurence, associate professor of architecture at Clemson University School of Architecture, cites Leatherbarrow as a particularly influential figure who helped make the program rigorous and scholarly, while still allowing it to be connected to culture outside the discipline. When studying with the late Joseph Rykwert, “I used my Latin to read a treatise by Leon Battista Alberti from 1450 that is considered the first modern western treatise on architecture, " Laurence says. “I cherish those experiences going down rabbit holes and really researching the canon, including my favorite, the theories of the 17th century scientific revolution.”

Leatherbarrow taught a class in what was then the Perkins Rare Book Library, analyzing key manuscripts from the history of architecture theory that can only be found in that collection. He points out that while architecture students learn to draw, they need to learn to research as well. “In a school that bridges so many disciplines, the graduate group is a key part, as it qualifies the research that architects do and helps broaden the horizons of what is possible at the school,” he says.

“I sometimes think that, for me, [the program] provided a remedial humanities degree,” Bill Braham (MArch’83,PhD’95), Andrew Gordon Professor of Architecture who directs the Master in Environmental Building Design program at Weitzman, says of his experience as a student in the PhD program. “It provided me with a foundation and perspective that has made it possible for me to work back and forth across disciplinary divides.”

These interdisciplinary and humanistic principles remain core to the program, but the role of doctoral research and the interests of students have shifted. For decades the program was focused on the history and theory of architecture; most recently, with more faculty joining the architecture program with PhDs in technology, a growing number of dissertations are now written on structural computation and environmental design.

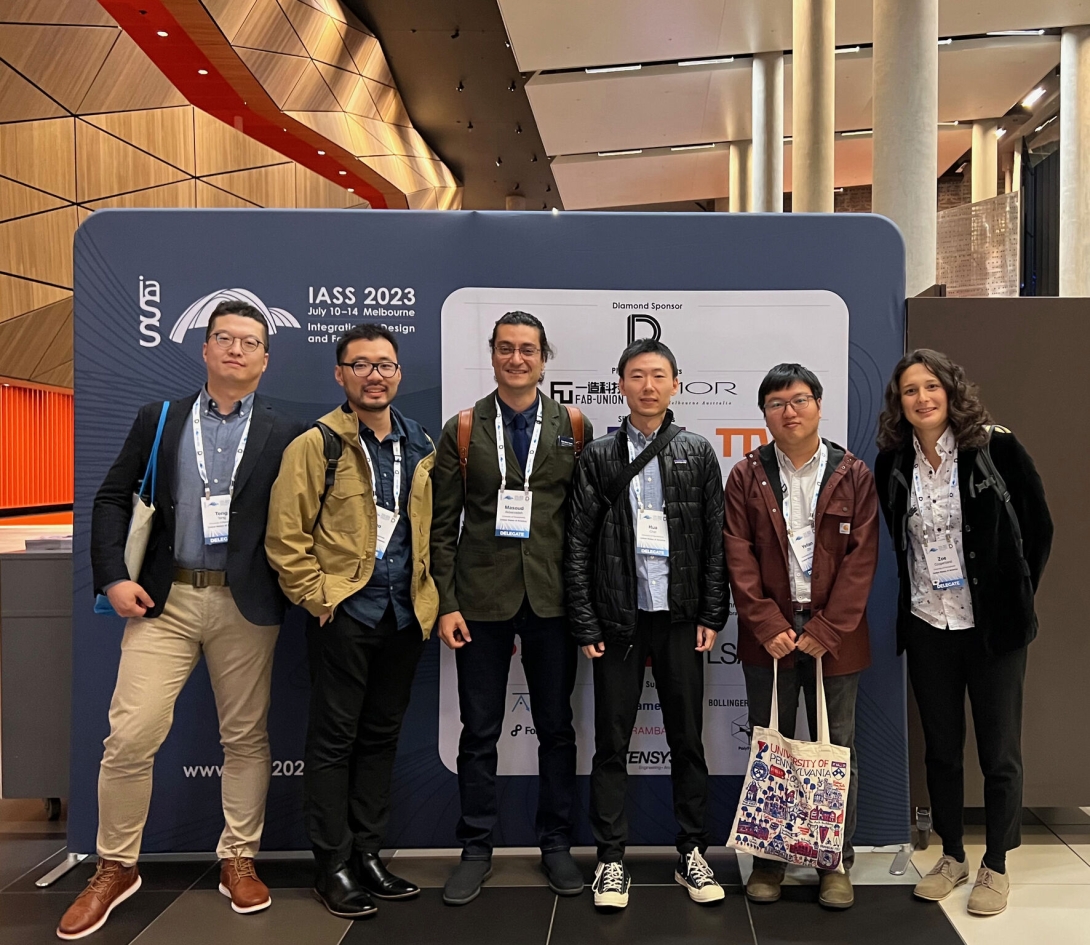

A growing number of dissertations are written on structural computation and environmental design. Masoud Akbarzadeh (center), associate professor of architecture and director of the Polyhedral Structures Lab, and PhD in Architecture students (left to right) Teng Teng, Yao Lu, Hua Chai, and Yefan Zhi at the annual symposium of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures in Melbourne, Australia in July of 2023.

Perkins wasn’t alone in his quest to integrate architecture and engineering. He brought in leading figures such as Professor Emeritus Peter McCleary to teach structures and technology. On the faculty for two decades, legendary engineer Robert le Ricolais used “mathematics and physics, engineering and zoology in search of new visions for structures,” while his colleague Ove Arup sent his colleagues to Penn to teach a studio in the early 1970s at the request of McCleary, who had been an employee of Arup’s firm. This vibrant culture set the tone for many students to take up the mantle of integrated practice, and to use theory alongside built work to extend their impact on the discipline.

One such alum is Tonkao Panin (PhD’03), principal architect of Bangkok-based Research Studio Panin and professor at the Faculty of Architecture, Silpakorn University. An architect with an academic practice, Panin credits the PhD program for her diverse works, including teaching, writing, and running her own firm. She recalled the Bauhaus connection to engineering and courses on Philosophy of Technology as particularly important for her multidisciplinary career path. “The program's unique approach combined theory with practical applications,” Panin says. “It was instrumental in my development.”

Urban planners have also benefited from the expansive, interdisciplinary culture at Weitzman. “With the majority of greenhouse gas production coming from the built environment, the role of architecture and urban design is central,” Weitzman Dean Fritz Steiner says. “Penn was one of the first US universities to offer a PhDs in both Architecture as well as City Planning. Our graduates have had huge influences on those fields as academic disciplines.”

“The most important influence of this program on me as an urbanist is a profound understanding of the city as a complex entity,” says Zhongjie Lin (PhD’06), a graduate of the PhD in Architecture program who is now the Benjamin Z. Lin Presidential Professor of City & Regional Planning. “This analytical framework ensures that urban designs are not merely aesthetic interventions but rather responsive and sustainable guidance that enhance the urban experience.”

While many scholars today are grappling with architecture’s eurocentrism, and expanding the canon to include global perspectives and histories of architecture, the program at Penn, and PhD research in general, has long been global in outlook. Based on his experiences at Harvard and Penn, Perkins was tasked by the United Nations with establishing schools in India, Turkey, and Pakistan. In addition to positions across the US, Penn’s PhD in Architecture graduates are working as deans and industry leaders abroad—from Thailand and Seoul to Morocco and Kuwait.

After attending the National School of Architecture (ENA) in Morocco and the Architectural Association in London, Hassan Radoine (PhD’06) came to Penn for his PhD. He then returned home to Morocco to help jumpstart the architecture curriculum at his alma mater. “Wherever I go now, I am an international expert and it really feels like it came from being at UPenn,” he says. Following in Perkins’s footsteps, Radoine returned to ENA to launch two master’s programs and the first PhD in architecture program in Morocco.

“The Penn PhD program is graced with incredible faculty and students,” says Franca Trubiano, associate professor of architecture and chair of the graduate group. Trubiano is pictured with PhD student Ji Yoon Bae at the UIA 2023 World Congress of Architecture in Copenhagen, Denmark in July of 2023.

Previewing the Symposium

Reflecting on this history and on the program’s possible futures, the Resources, Resilience, and Resistance symposium will welcome graduates back to join in conversation about the state of advanced architectural education, and the challenges and opportunities ahead for doctoral research. The invited speakers represent myriad research institutions with formidable graduate architecture programs of their own, including Theodora Vardouli (McGill), Lydia Kallipoliti (Columbia), John Ochsendorf (MIT), S.E. Eisterer (Princeton), Ana Maria Leon (Harvard), and Jonathan Massey (Michigan).

The symposium’s first theme, “Resources,” is an investigation of how future doctoral research in architecture can engage with non-extractive technologies, waste valorization in building construction, circular and carbon capturing building materials, materially-efficient structures, optimization of lightweight structures, as well as innovative archives, pedagogical traditions, and history as an architectural resource.

The second theme, “Resilience,” responds to current discussions around climate resilience, bioremediation/extreme heat remediation, regenerative architecture, energy-/thermally-efficient systems, healthy materials, energy policy, underinvestment in the humanities, and design as public discourse (or lack thereof).

The third theme, “Resistance,” is an assessment of architectural decolonization, environmental/social/labor justice in the built/urban environment, space and gender studies, critique of technological determinism, and informed AI.

The symposium is part of a yearlong celebration organized by Weitzman that included two online discussions last fall. Participating were recent alums Elie Haddad (Lebanese American University), Xavier Costa (Northeastern), Nadia Alhasani (University of Sharjah), Hassan Radoine (Mohammed VI Polytechnic University), Grade Ong (Thomas Jefferson University), Taryn Mudge (Temple), Nan Ma (Worcester Polytechnic Institute), and Miranda Mote (Penn).

Trubiano is excited for the program’s future, and hopes that the symposium will help chart a course for its evolution. “The Penn PhD program is graced with incredible faculty and students. Our faculty have garnered significant trust in the funded research community and contributed critical questions to the debate on material resources and environmental resources. Our students have championed alternate voices and empowered visions of social justice in the search for an empathic form of scholarship. I am confident we can continue to make an impact around the world.”