Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

“An integrated series of new connections, from streets and sidewalks to bike paths and pedestrian trails, are essential to the successful development of the Delaware Riverfront.”

-- Rina Cutler, deputy mayor for transportation and utilities, City of Philadelphia

Every Philadelphian should have access to our rivers. More than sixty thousand people live within a ten-minute walk of the central Delaware River, but fences, I-95, vacant properties and blight make the river a very difficult destination to reach (33). Insufficient sidewalks, bike lanes, paths and crosswalks discourage all but the most fearless pedestrian or biker from traveling to the river. Philadelphia can and should guarantee public access to the river by passing a zoning requirement that all new developments must provide convenient, safe public access to the river from the nearest public street. Pennsylvania already requires owners who lease state-owned riparian land to ensure public access to the river. The requirement could be met through the creation of safe paths designed exclusively for pedestrians and cyclists, sidewalks bordering an existing public or private road or a new road designed to accommodate cars, pedestrians and cyclists.

A safe, secure and comfortable system allowing pedestrians and cyclists to travel along existing roads to the central Delaware riverfront is also essential. Many existing roads in the central Delaware were built for cars and do not provide bike lanes and adequate sidewalks for cyclists and pedestrians. The reason for this is simple: in the past, it was an industrial area that needed freight rail and trucks and had little or no demand for recreational access. Providing sidewalks and bike lanes will help residents walk and bike to the river, lessen congestion by providing an alternative to short car trips and improve the attractiveness of the area to new residents and businesses.

Actions must be taken to increase the safety of pedestrians and cyclists traveling on the highway-like Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard and throughout the area. Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard poses the greatest challenge to a walkable and bikeable central Delaware, as it is currently a wide, high-speed, congested road with three to four car lanes in each direction. East-west streets that connect neighborhoods to the riverfront must also be able to accommodate Philadelphians on foot and on bike.

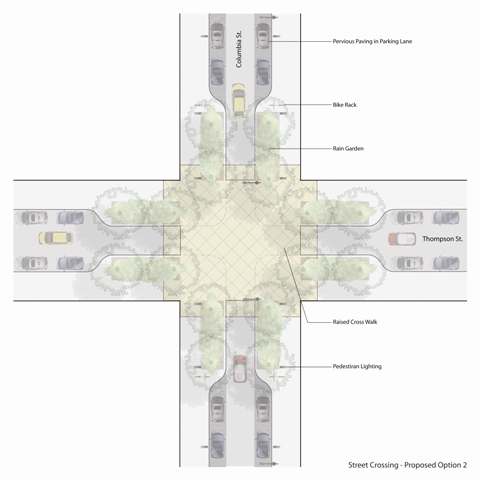

Simple enhancements at intersections such as widened sidewalks and more visible crosswalks can significantly improve pedestrian connectivity at the river's edge.

Here are some of the ways in which this can be accomplished:

- Build and improve sidewalks to create wide, well-lit and well-maintained sidewalks on both sides of Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard and on connecting east-west streets. While wide and relatively new sidewalks exist along stretches of Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard at Penn’s Landing, there are long stretches south of Penn’s Landing and near the Girard Avenue Interchange that have no sidewalks at all. Driveway curb cuts should be limited to make the sidewalks easier and safer to use by all residents, including seniors and people with disabilities.

- Build safe crosswalks at all four corners of every intersection of Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard to permit pedestrians to cross safely. Crosswalks should be highly visible, with striped markings and pedestrian lighting. No crossing should be wider than 40 feet or include more than one turn lane in either direction because this design is unsafe for pedestrians (34). In places where the existing crosswalk exceeds 40 feet, medians can be used to allow pedestrians to stop in the middle of the road and to confront traffic traveling in one direction at a time.

- Add bike lanes to key routes to the river. Cyclists have only three east-west bike lane connections to the river: Spring Garden Street north of Center City and Snyder and Oregon Avenues in South Philadelphia. Bike lanes on the riverfront have some dangerous gaps, primarily at the northern end of the project area (35). Bike lanes that start and stop make it dangerous to bike in the corridor.

New York City cyclists enjoy new, wide bicycle lanes along 9th Avenue in Manhattan. The bicycle lanes are separated from vehicle traffic by the parking lane to improve safety.

Early progress along the riverfront could serve as a demonstration project for bike-friendly initiatives. Improvements should include (1) the addition of safe bike lanes to portions of Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard that lack them, (2) the addition of bike lanes to one or two east-west roads that will improve access from Center City and nearby neighborhoods to the north(35a), (3) the enforcement of parking restrictions to prevent cars from parking in existing bike lanes and (4) the installation of bike racks for cyclists along Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard to allow more people to bike to the river and stop at various destinations during the course of a ride.

In the longer term, a full analysis of the area should be completed, one that examines needed improvements in safety and in pedestrian and bicyclist access. This analysis could be a part of either the master-planning process or the city Pedestrian and Bicycle Plan already underway (36). Also in the longer term, as the civic vision is implemented, all street extensions should include bike lanes and wide pedestrian sidewalks.

A "green street" in Denver includes tree plantings and stormwater retention gardens.

Short-Term Actions

- Adopt zoning that requires owners to provide public access to the river.

- Identify necessary improvements to central Delaware intersections, including better crosswalks and pedestrian lighting to make the area friendly to pedestrians and bicyclists.

- Require improvements to pedestrian and bicycle crossings as a part of any changes made to roads by developers or government.

Longer-Term Actions

- Through the master-planning process, define a complete list of high-impact improvements to existing roads, paths and sidewalks. Work with the Philadelphia Department of Streets to schedule these improvements in its five-year plan.

- Add signs and lighting to guide pedestrians and cyclists to the river and to increase the river’s presence in the city.

- Create pedestrian paths and active recreation areas under I-95 where possible.

- When creating extensions of key east-west streets to the river, make them “green streets” that provide lanes and sidewalks for cyclists and pedestrians. Line the road and the median with trees and shrubs to absorb stormwater and prevent flooding of streets and homes.

- Wherever possible, transform existing streets into green streets by including bike lanes and sidewalks and increasing plantings.

Civic Actions: What Philadelphians Can Do

- Identify where painted pedestrian crosswalks, stop signs, bike lanes or sidewalks could be added to improve access to the river.

- Identify opportunities to combine routine public actions, such as street repair, transit improvements and grants for other purposes, with improvements to pedestrian and bicycle access.

- Identify locations from which you can see the river. These view corridors will be particularly important pedestrian-access points.

- Identify locations where fences can be torn down to increase access to the river. Approach owners about taking fences down and allowing the public to cross their land.

- Identify for the waterfront manager where abandoned properties, poor lighting or other conditions deter residents from walking to the river.

Along the central portion of Seattle's waterfront, extended streets provide frequent public access to the water's edge.

Benefits and Impact

Economic: Allows customers to reach riverfront retail and entertainment destinations, reduces number of public parking spaces needed and improves public health through exercise.

Environmental: Encourages residents to walk or bike rather than driving to river; reduces traffic and pollution.

Community: Transforms riverfront into neighborhood and citywide asset, reduces pedestrian injuries and encourages people to travel by bike and on foot.

Impact on City Budget: The costs of pedestrian and bicycle improvements vary. To restripe a crosswalk at an intersection costs approximately $10,000 (37). To create a median island costs about $15,000 (38). Putting in a new concrete sidewalk costs $50 to $60 for 12 feet or 3 square yards (39). Pedestrian lighting (including foundation, wiring, installation and fixture) costs about $10,000 per light. Overhead lights without a pole or foundation cost about $3,000 per light (40).

Other Cities Have Done It - We Can Too

Since 1992, New York City has required every large-scale waterfront property to provide public access (41). Seattle made a priority of improving conditions for cyclists and pedestrians by completing a Bicycle Master Plan in 2007 and a Pedestrian Master Plan in 2008. In accordance with the plan, Seattle added miles of new bike lanes, constructed two new bike trails and improved two hundred curb ramps and 750 crosswalks throughout the city to encourage residents to bike. It worked. Bicycle commuters have increased by 600 percent since 1992. Today, six thousand cyclists travel daily. The city has also built blocks of new sidewalks and repaired existing sidewalks in order to encourage residents to walk (42). Chicago added a hundred miles of bike lanes and ten thousand bike racks to create a more sustainable city (43).

Battery Park City, NY

Funding Resources

- Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) (PennDOT and DVRPC) funds projects that reduce air pollutants from transportation-related sources. Funding approved for 2006 funding cycle ranged from $20,000 to $20 million.

- Transportation, Community and System Preservation Program (TCSP) (FHWA): A total of $270 million is authorized for this program through 2009 for projects that improve the efficiency of the U.S. transportation system, reduce the environmental effects of transportation and ensure efficient access to jobs, services and centers of trade. Program has funded essential pedestrian and bicycle upgrades.

- Trump Tower and Penn Treaty Tower riparian lease agreement:Under the state’s riparian land lease, Trump and Penn Treaty Towers must dedicate 50 cents for every square foot of building space to implementing the Civic Vision for the Central Delaware.

- Four percent of gross casino revenues are specified by the Commonwealth’s Gaming Act to offset increased city operating costs for managing the impact of the casinos on transportation, the police, and the health, safety and social welfare of areas surrounding the casinos.