Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard is a state highway that provides access north-south along the river. Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard is slated for millions of square feet of development that could bring thousands of new cars to the area. This already congested road does not have the capacity to absorb large amounts of new traffic.

Strategic traffic management is needed to ensure that residents and visitors can reach the riverfront. If the casinos and other new, large-scale developments swallow up all the traffic capacity or make the area even less safe for pedestrians and cyclists, then no matter how attractive the waterfront is, few residents will choose to go there. Lowering existing traffic congestion and ensuring that the area can handle anticipated increases in traffic is essential to the health of the central Delaware area.

Managing parking presents another key challenge for Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard. Until pedestrian and transit improvements are in place, the car is the only convenient way to reach the river. It is therefore tempting for developers to create a sea of surface parking or exposed parking podiums to accommodate cars. Parking-design standards need to be put in place to prevent cars from dominating the riverfront, ruining water views and taking up space that could be dedicated to people.

In this section, we discuss actions to address traffic congestion and the parking options available to owners, as well as comparing their costs and benefits.

Key Actions to Lower Traffic Congestion

Synchronize traffic signals to reduce congestion by 10 percent.Timing traffic lights along Delaware Boulevard will allow traffic to flow with fewer delays. The goal is to coordinate traffic signals to allow a series of cars to pass through a particular segment of road without stopping for red lights. Once that group of cars clears the light, the light turns red. This avoids the constant stop-and-go that drivers experience currently on Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard. A computerized system can monitor and shift signal timing in either direction during the course of the day as traffic patterns change. Synchronization also saves on gas and emissions. Portland, Oregon and surrounding suburbs synchronized their traffic signals and saved 1.75 million gallons of fuel and reduced CO2 emissions by 15,000 tons.59 Transportation experts estimate that timed traffic lights can reduce congestion by 10 percent (60).

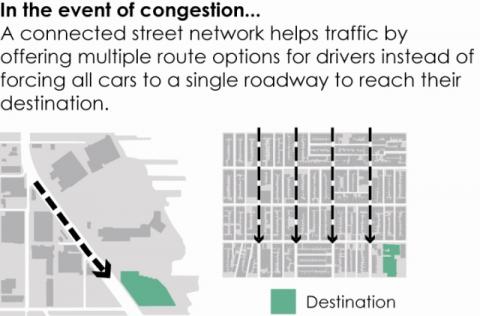

Extend east-west cross streets to the river and create new intersections that can handle one to two hundred turns per hour. Extending east-west streets to the river gives drivers several different routes to travel to the river and a choice of where to turn onto Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard.

In the event of congestion, a connected street network helps traffic by offering multiple route options for drivers instead of forcing all cars to a single roadway to reach their destination.

Build a streetcar line to add the capacity of two and a half lanes of traffic in each direction. A modern streetcar can carry two to three thousand passengers per lane, the same amount of people as two and a half auto lanes in each direction can carry. Offering transit as an alternative will remove private cars from the traffic stream and give residents and visitors an alternative way to travel to and along the river.

Improve bicycle connections and pedestrian connections to increase the capacity of Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard by up to 10 percent. Creating a safe, convenient system for walkers and bikers will allow residents to take short trips to and along the river without getting in their cars, traveling a short distance and turning into another driveway. The reduction in short car trips will increase through-traffic capacity by up to 10 percent. Downtown and river-neighborhood residents will start to take short trips on foot or bike once they are confident that it is safe to do so.

Build parking garages at easy drop-off locations, in particular next to all I-95 exit ramps, to free up to 25 percent of the traffic capacity on Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard. By building easy car drop-off locations and creating a safe pedestrian environment, the riverfront area can become a “park once district” where people park for the day and then visit several destinations by walking or using transit. Eliminating short car trips from one part of the riverfront to another could free up 25 percent of the through capacity along the boulevard.

Regulate private casino buses. Casinos attract large numbers of private buses for the general public, as well as junkets that transport gamblers and receive compensation from their passengers’ gambling losses. The South Jersey Transportation Authority (SJTA) restricts buses and junkets, requiring them to obtain permits and to drive only on certain allowable routes (61). The Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board has agreed only to regulate junket operators (but not private buses) and to require them to certify their planned routes and bus-storage locations. The state also prohibits the storing or stacking of junket buses on public roadways and idling for more than ten minutes, no matter what the weather conditions (62). Philadelphia should pass legislation to apply these regulations to private casino buses as well as junkets.

Key Actions to Encourage Parking Options That Make Parked Cars Less Visible along the Riverfront

Large portions of the central Delaware riverfront are dedicated to cars. There is currently more surface parking than there is park space along the central Delaware. In the South Philadelphia Pier 70 shopping district, parking lots cover more land area than stores cover. Foxwoods Casino plans to construct over five thousand on-site parking spaces—over one spot per slot machine. As a result, effective parking location and design is critical.

Public parking-garage revenues can help finance riverfront projects. Operations and maintenance for Millennium Park in Chicago are entirely financed by revenues from a vast parking garage beneath the park. Many waterfront open-space developments, including New York’s Hudson River Park, also receive significant revenues from paid parking areas. Chicago went one step further earlier this year by leasing two parking garages that will yield enough revenue to finance fifty park-improvement projects throughout the city.

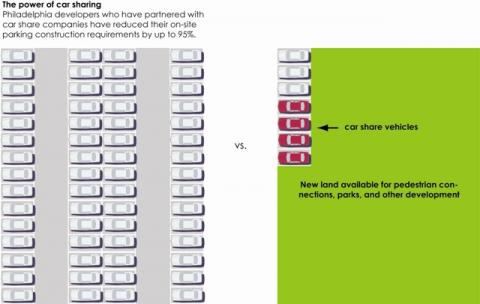

A new streetcar line and the use of PhillyCarShare will reduce parking-space needs. In a few hours, a streetcar line can deliver a huge number of people to the river; if the same number of people drove to the river, their cars would fill twenty parking garages. PhillyCarShare, which allows residents to rent cars by the hour, can also help limit the need for parking. Including PhillyCarShare spaces in residential projects will allow for fewer required parking spaces.

In the short term, limit the visibility of surface parking and lower minimum parking requirements. Until sales and rental prices are so high along the central Delaware that valuable land cannot be devoted to cars, many developers will choose to store cars in low-cost surface lots or parking podiums that place cars in the most visible, street-level floors of a building. As a result, in the short term, a zoning overlay should establish rules to construct well-designed parking solutions by wrapping surface parking lots or structures with stores, restaurants or other active uses to shield the facilities from view. Where wrapping the parking lot with buildings is not possible and the lot is located by the street and public sidewalk, owners should be required to provide a landscaped strip of trees or planters to screen the parking lot from view. The zoning overlay should also allow lower parking-space minimums for properties near transit stops that offer access to PhillyCarShare vehicles and good bicycle and pedestrian access.

In the longer term, as land becomes more valuable, provide incentives to developers to encourage the use of attractive and appropriate parking solutions. At this point, hidden, shared and remote parking will become options that can serve major destinations along the river.

- Create public parking at easy drop-off locations next to I-95 exits. The best location for public garages in the riverfront area is on the city side of Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard, immediately adjacent to exit ramps. This allows the driver to find parking quickly and keeps cars off congested riverfront roads. Some existing stretches of land under I-95 may also provide space for needed parking.

- Remote parking with free shuttle service will allow Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard to better handle up to thirty thousand more cars a day—the anticipated increase from casino traffic. Numerous Center City developers already operate shuttles to employment centers from remote parking facilities.

- Underground parking is expensive, particularly near water, but it allows a developer to provide the most units of retail, housing or office space on the surface of the property while keeping parking hidden.

- Automated parking lots use advanced machinery to accommodate more cars while using 50 percent less space than traditional structured parking. Construction costs may also be lower because elements such as ventilation systems, pedestrian elevators and emergency staircases are not necessary.

The power of car sharing: Philadelphia developers who have partnered with car-share companies have reduced their on-site parking construction requirements by up to 95%.

Short-Term Actions

- Perform a traffic-signal synchronization study to determine how signals should be timed for maximum improvement to traffic flow.

- Synchronize traffic signals on Delaware Boulevard to reduce congestion by 10 percent.

- Regulate casino buses.

- Extend east-west cross streets to create more turn options onto Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard.

- Establish zoning that provides incentives for projects that use best practices for parking.

- Encourage owners to include designated car-share and bicycle-parking spots in existing developments and require these for future development of riverfront property.

- Explore potential sites for public parking garages next to I-95 ramps.

- Improve pedestrian and bicycle connections to increase Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard capacity by 5 to 10 percent.

- Explore parking as a tool with which to finance riverfront improvements.

Longer-Term Actions

- Create a streetcar line to increase by nearly 100 percent the capacity of the boulevard to transport people.

- Complete a parking study to examine the parking needs of the area before and after the completion of the streetcar and pedestrian and cyclist improvements. Set parking ratios as a part of the area’s master plan.

- Build parking garages at easy drop-off locations to add 30 percent more traffic capacity.

Civic Actions: What Philadelphians Can Do

- Advocate for regulations on the routes and emissions of casino buses.

- Advocate for progressive parking and transportation policies in the central Delaware.

- Start neighborhood-based programs that promote walking or biking to the river rather than driving.

Benefits and Impact

Economic: Reducing traffic will improve business viability by making riverfront properties easier to reach. Parking garages could be financing tools. Limiting parking creates more land for people to occupy.

Environmental: Reduces emissions from congested traffic, improves air quality and increases the riverfront’s attractiveness by concealing parking.

Community: Improves access to the river, connects river neighborhoods and decreases automobile pollution linked to asthma, heart disease and cancer.

Impact on City Budget: Signal synchronization along the Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard corridor would cost in the range of $200,000 to $400,000, depending on the complexity of the system. In the short term, developers should be offered incentives such as density bonuses to build more expensive, more attractive parking structures. After the initial capital costs of public garages have been paid, parking fees can help finance the ongoing maintenance of public spaces.

Other Cities Have Done It - We Can Too

Los Angeles has begun a $150 million effort to reduce congestion throughout Los Angeles by synchronizing all of the city’s 4,385 intersections with signals by 2011. Operation Green Light in Kansas City relies on traffic-signal coordination to reduce traffic congestion. San Francisco is extending streetcar lines to its northern waterfronts because its administrators know that transporting ever-increasing numbers of visitors through improved transit services rather than automobile access avoids greater traffic headaches and spillover parking problems in adjacent neighborhoods (63). Chicago provides density bonuses for developers who conceal parking or build underground parking to ensure that cars don’t dominate the city landscape. Traffic-management and parking restrictions are key tools used across the country that help create more attractive communities.

Funding Resources

- Foxwoods Casino: Foxwoods has agreed to implement traffic-signal synchronization as a part of its traffic-mitigation responsibilities during Phase 1 of its building plans.

- State Gaming Act: Requires that 4 percent of gross casino revenues be earmarked to offset increased city operating costs for managing the casinos’ impact on transportation, police, and the health, safety and social welfare of adjacent areas.