Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

A Civic Vision For the Central Delaware: Implementation

With major riverfront development on the horizon, an effective, open and transparent implementation strategy is crucial to ensure that the central Delaware riverfront is developed in accordance with citizen values. Civic groups are concerned about the impact of development on their communities, and the coordination of public and private investments will help to ensure that the riverfront becomes a public asset to the city of Philadelphia. While current public-sector efforts are in effect to oversee riverfront development, to date they have fallen short of the coordination needed to create a world-class riverfront.

Implementation (pdf)

Previous chapters and Chapter Nine (“Phasing”) offer numerous suggestions for short-term improvements that could constitute first steps toward the realization of the civic vision. However, larger choices about financing, management and oversight will also need to be made for the long-term revitalization of the riverfront. In other cities, major infrastructure improvements along riverfronts have been financed through innovative public-investment methods. These have included the creation of tax increment financing districts and special services districts and the use of dedicated sales tax revenue. These and other funding mechanisms would need to be established in conjunction with riverfront development strategies that include management, oversight and civic engagement.

Purpose

To develop a cohesive implementation strategy that will aid the city in making the vision presented in this report a reality.

Goals

The central Delaware riverfront is a large area, and development will occur over many years, requiring the ongoing commitment of both public and private stakeholders. To achieve the key objectives of the vision, the following goals must be addressed:

1. Establish Creative Strategies for Financing Public Improvements: The city of Philadelphia should consider tax abatement districts and special services districts, but also look to other financing methods.

2. Create a Strategy for Comprehensive Implementation, Management and Oversight: Build on existing governance along the riverfront and establish a set of required functions for agencies invested in the future of the riverfront.

3. Modernize Public Policy: Forward-thinking zoning regulations and land-use policy can catalyze quality development and promote sound urban-design practices. These changes will require new policy standards that incorporate community input.

4. Continue the Dialogue: The Central Delaware Advisory Group has called for sustained public input—a hallmark of this planning process—to continue through the implementation stage.

Each of the implementation goals is addressed in more detail in the following sections. Each section outlines overarching goals that could serve to inform stakeholders of the wide variety of tools available for implementation. There areno single recommendations for implementation; rather, we offer a set of recommended actions that Philadelphia can take to ensure that the goals of the civic vision guide the development along the central Delaware for generations to come.

Goal 1: Establish Creative Strategies for Financing Public Improvements

The city of Philadelphia should consider tax abatement districts and special services districts, but also look to other financing methods.

The Civic Vision for the Central Delaware will be realized through a combination of public and private investments. The long-term infrastructure improvements recommended in the plan include the creation of Delaware Boulevard (complete with a riverfront transit system), the creation of numerous new park spaces and a continuous trail, and the construction of a street grid that extends major streetsto allow riverfront access. Taken together, these improvements offer a framework for further development.

The following are choices the city can make when developing its strategy for revitalizing the riverfront. They are not mutually exclusive, as each has distinctbenefits that should be explored. Today, the city uses many mechanisms to attract private development and manage public improvements, including property-tax abatements, special services districts, Keystone Opportunity Zones, tax increment financing (TIF), and transit revitalization investment districts (TRID). Most of these programs could be used to fund some of the large-scale improvements to publicspace presented in this civic vision. However, achieving the vision will alsorequire new financing strategies and partnerships.

Financing Options for the Implementation and Maintenance of Infrastructure

In order to create the infrastructure critical to enhancing the central Delaware riverfront, Philadelphia would have to supplement outside funding with its own funds, likely raised through the issuance of bonds and local taxes. The following financing programs are in use throughout Philadelphia:

Tax Increment Financing (TIF)

As is evident in major cities around the United States, tax increment financing can be a valuable public-finance tool for redevelopment projects. TIF funds are used to leverage public funds to promote private-sector activity in a targeted district or area. To date, Philadelphia has used TIFs sparingly, mostly on single development parcels. However, using the mechanism to establish one or more area-wide TIF districts along the central Delaware riverfront could provide Philadelphia with a near-term revenue stream to help fund some of the infrastructure and public-space improvements outlined in previous chapters.

TIF districts are typically established in areas with redevelopment potential. They enable municipalities to raise money to finance essential infrastructure improvements by leveraging public-sector bonds based on future tax gains. The city of Philadelphia continues to receive property-tax revenues generated by existing properties in TIF districts as of the “base year” (the year in which the TIF district begins). However, tax revenues generated by increases in real property values following the TIF’s establishment, referred to as the increment, are typically deposited into a trust fund and go to repay the bonds used to fund specific initiatives. Property-tax revenues collected by the local school district (as well as any other special taxing district) are not lowered by the tax increment financing process. Depending on a particular state’s enabling legislation, tax increment revenues can be used immediately, saved for a particular project or bonded to maximize available funds.

Establishing a TIF allows the city to invest selected new property-tax dollars into the neighborhood from which they came (instead of into the city’s General Fund) for a defined period (typically twenty years). Since it is assumed that significant increases in tax revenue will be generated as a result of redevelopment, this increase is used to leverage the issuance of bond funds that can be spent immediately on public-works projects that will further increase property values within the district. The widespread use of TIF reflects its success as a key tool to finance public improvements in cities across the United States. Chicago alone contains over 150 TIF districts. Millennium Park was financed in this fashion, and its $340 million public investment is projected to yield $5 billion in private investment in the surrounding area in its first ten years of operation. Similarly, Atlanta expects to earn a twenty-fold return on the $1.66 billion bond that the city leveraged for its Beltline project.

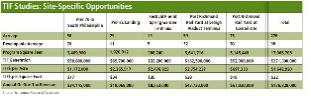

Four Sample TIF Sites

An economic analysis completed by Economics Research Associates (ERA) of Washington, D.C. illustrates the potential of four sample sites for TIF financing along the central Delaware riverfront: Pier 70 in South Philadelphia, Penn’s Landing, Festival Pier at the foot of Spring Garden Street, and portions of the Port Richmond rail yards (a total of approximately 243.5 acres). Assuming a market-supportable, prototypical redevelopment program on each of these four sites, ERA estimates that the four sites combined could leverage up to $371 million in TIF bonding capacity, which could be made available for public improvements; redevelopment on these four candidate sites could also generate non-TIF tax revenues of up to $177 million per year that could be used for citywide services.

A Sample TIF District

If implemented along the central Delaware, a TIF district would have the potential to leverage funding that could be used for district-wide infrastructure investment, such as constructing the greenway or portions of the new street grid or undertaking improvements to Delaware Boulevard. To test the potential of a large TIF district on the central Delaware, the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (the city’s designated agent to handle the TIF program) analyzed anticipated yields from a sample TIF district drawn to encompass a portion of the riverfront facing high development pressure: the area from the Benjamin Franklin Bridge north to the PECO Delaware Generating Station (a total of approximately 120 acres). Taking into account $1.9 billion in anticipated construction over the next twenty years (and a percentage of tax-abated properties), the study highlights the possibility of realizing up to $300 million that could be dedicated to the early construction of parks, streets and the boulevard along the central Delaware. Further, this development could generate up to $25 million in annual non-TIF tax revenues during the twenty-year TIF term, including wage, business and other taxes.

The analyses conducted by ERA and PIDC are meant to demonstrate the potential of TIF districts to capture significant funding to help the city finance much-needed public-infrastructure improvements along the riverfront (either specific or through the creation of a district).

Aker: Settled in 1999, the largest TIF district to date in Philadelphia is the Aker Shipyard, which received $30.9 million in financing for $489 million of development.

However, a detailed land plan and review process is necessary to establish a TIF district. In Philadelphia, the land within a TIF district must also be within a certified redevelopment district, as authorized by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority (RDA). All land located south of Spring Garden Street in the project area is eligible for redevelopment according to the RDA; this section represents about 60 percent of the total project area’s acreage. TIF districts could be established on land that is not yet certified if the district meets the stringent criteria for blight certification, which were updated by the state in 2006. Existing redevelopment areas do not need to be recertified under the new criteria until 2013. Further, the extent of the TIF capture may fluctuate in future years, as incentives like the ten-year tax abatement and Keystone Opportunity Zones may apply to properties within a proposed TIF district. See the “Market Incentives” on page 180 for more information.

In accordance with the civic values and principles, public participation should be an important part of the TIF designation process to ensure that this tax revenue is used specifically for public infrastructure investment. The city’s riverfront is emerging as an important location for new development, and the TIF could provide an opportunity for financing public amenities that secure the riverfront as a citywide asset and enhance its long-term redevelopment potential.

One of the key challenges of a TIF district is that actual TIF revenues may fall short of projections, since a TIF district generally has only incremental property taxes as its revenue source. Shortfalls could occur when the level of anticipated new development is not achieved, or when property-tax abatements or exemptions to induce development are implemented (such as the ten-year residential property-tax abatement program renewed by City Council in 2007). To reduce these risks, a municipality can designate a larger district that spreads the risks over a larger area, add other potential revenue sources such as parking into the mix, or allow joint financing of TIF districts that distributes the costs of improvements in one district across all of the city’s TIF districts, thereby reducing the burden on any one district. Loan guarantees could also be provided by developers who would benefit from the public improvements made.

In conclusion, riverfront development will be an ongoing part of Philadelphia’s future and should be considered a critical element of its overall economic-development strategy. The TIF analyses demonstrate the potential for the city to generate significant funds for infrastructure improvements that would create the physical framework to support future development. While a TIF district does not freeze property taxes as the ten-year tax abatement does, the return-on-investment for the private sector can be substantial. The bond funds leveraged by projected tax revenues can be reinvested within the TIF district immediately to finance public amenities that would not otherwise be possible. This can be expected to improve quality of life and in turn increase property values and demand for riverfront development. While the preliminary analysis demonstrates the opportunities on four sites and one potential district (covering only 31 percent of the study area), it is likely that even greater opportunities exist to leverage the future tax revenues generated by other parcels, including SugarHouse and Foxwoods Casinos, should they be built. This is just one financing option that the city could use to develop the central Delaware.

Spotlight: Applying TIF Districts to Casinos

Given the prospect of gaming on the central Delaware, Philadelphia should consider the multitude of financing options that could be used to finance infrastructure

improvements along the riverfront. Tax Increment Financing (TIF) provides an opportunity for the city to receive an up-front payment bonded against future tax

revenues, helping to accelerate development of important capital improvements. If the city created TIF districts on the two proposed casino sites, the revenue

generated would exceed what the city would receive through negotiated tax payments or Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOTs). These TIF dollars could be used to fund essential elements of the civic vision, including these:

- Development of a riverfront trail,

- Development of a mass transportation system,

- Development of Penn’s Landing as a signature green space,

- Connections to and amenities for adjacent neighborhoods, and

- Arts and cultural amenities.

The city may have missed an opportunity by not already establishing a TIF district between the casino sites.

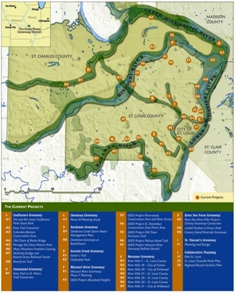

(In 2000, 68 percent of voters in St. Louis counties approved a one-tenth of one-cent sales tax to fund a Clean Water, Safe Parks and Community Trails Initiative. The dedicated tax generates about $10 million per year and has funded the development of interconnected greenways, parks and trails.)

Transit Revitalization Investment District (TRID)

Enacted in 2005 by the Pennsylvania legislature, the Transit Revitalization Investment District Act encourages city officials, transit agencies and the development community to plan for and implement transit-oriented development. Like TIF districts, TRIDs leverage future real-estate tax revenues to support transit-related capital projects, site development and maintenance within the defined district. While this program is still in its infancy, there is the potential to utilize this financing mechanism along the riverfront–particularly along Delaware Avenue/Columbus Boulevard. Philadelphia would first finalize a community-driven TRID planning study. Then, in cooperation with SEPTA, the city would form a management entity to administer continued implementation. The amount of the share of the new tax revenues to be reinvested in TRID-area improvements needs to be finalized with the school district and the city.

Dedicated Tax

Revenues from dedicated taxes can help provide funds to pay off debt incurred from the issuing of bonds. Pairing debt and taxation measures can help assure that a dedicated funding stream will be available to help fund implementation programs. This technique is often used for open-space acquisition, and Pennsylvania has demonstrated leadership in utilizing innovative public-financing strategies to fund land conservation. In fact, Radnor Township in Delaware County increased its real-estate transfer tax from 0.75 percent to 1 percent and dedicated the additional revenues to open space.

Capital Expenditures

Many cities support public investments through the annual allocation of funding as earmarked within the budget for capital improvements. The downside of relying solely on this funding source is that the annual revenues are often small, and it is difficult to sustain the funding when leadership and administration priorities change. However, budgeted public-sector investments are often important in providing the startup capital costs for implementation, management and oversight.

State and Federal Grants

While cities must supplement outside funding sources, federal and state funding programs provide opportunities for significant riverfront improvement. Some of the most promising state and federal funding sources include these:

Open-space grants are available from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR), which receives about $56 million per year from the Keystone Fund for community recreation, park and conservation projects across the state.

Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) provides over $1 billion for pedestrian and cycling trails through its Transportation Enhancements Grants. These could be used to finance early portions of trail development, such as the reconstruction of Pier 11 and the terminus of Spring Garden Street.

The federal Surface Transportation Program has many funding programs available for roads other than highways, as well as for road-safety improvements.

The Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Program offers funding for projects that reduce congestion and/or vehicular emissions to help achieve the goals of the Clean Air Act. Transit-oriented development would be eligible to receive such funding.

Pennsylvania Coastal Zone Management Program (managed by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection) has coordinated over $50 million for projects that protect and enhance fragile coastal resources.

Private-Sector Financing and Public-Space Development

When developing riverfront policy, many cities have incorporated provisions into their legislation requiring private developers to finance certain elements of public infrastructure in order to develop at the river’s edge. This is primarily accomplished in two different ways: development impact fees and mandated public-space development, which is required in the permitting process. Impact fees are one-time charges applied to offset the additional public-service costs that come with large-scale development. New residents and users boost infrastructure needs, and impact fees pass those costs on to the private sector. Fees must address local and regional impacts while ensuring that development is not deterred. Some states do not allow cities to enact impact fees, but they are legal in Pennsylvania.

Additionally, many cities have written zoning or permitting legislation that requires developers to provide capital improvements accessible to the public in order to build. Numerous municipalities have required that proposed riverfront developments include the construction of park and trail space in order to receive permits; they include Hoboken, Jersey City and Greenpoint/Williamburg in Brooklyn. Such a mandate would mean that public spaces would be developed piecemeal over time, but this method can be effective in areas with rising market value and a public sector with little funding for capital improvements.

Spotlight: Parking Revenue

Cities around the nation are starting to find creative ways to use revenue from parking garages and metered fees to finance public-space projects. Earlier sections of this report cite the use of waterfront and city parking funds to maintain parks and trails in cities such as New York, Chicago and Boston. Various planning initiatives in Philadelphia have presented innovative ideas on how to capture parking revenue. Released in January 2007, the Center City Residents Association Neighborhood Plan has a detailed implementation section that outlines various strategies to encourage quality development. These include proposing fifteen-year tax abatements on the construction of underground parking and reaching an agreement with the Philadelphia Parking Authority to raise on-street parking fares in the neighborhood, with some revenues returning to the community for streetscape improvements. The Philadelphia City Planning Commission (PCPC) describes similar initiatives in its transit-oriented development plans for Frankford Avenue and West Market Street. There, PCPC proposes that on-street parking be managed through the establishment of a parking bene.t district (PBD), which would designate the district’s parking-generated revenues for landscaping and maintenance. PBDs could also help subsidize transit passes and bike-storage facilities for community members.

Special Services Districts

Both SugarHouse and Foxwoods Casinos have offered to contribute $1 million annually to a special services district (SSD). If approved by City Council after neighborhood petition and public process, the SSD would establish an entity that uses an assessment tax imposed on commercial and/or residential properties (depending on whether it is a business or neighborhood improvement district). The proceeds are used for public-space maintenance, programming, security and other functions. One type of SSD being explored in other cities is a park improvement district (PID), which would capture funds from residences and businesses within two blocks of a park so that those who most benefit from the park contribute directly to its maintenance. PIDs work best in neighborhoods with new construction, a high percentage of owner-occupied households and a financial ability to pay an additional fee. Though SSDs can float bonds for capital improvements, their main functions are to supplement city services and to capture funding for neighborhood initiatives such as maintenance and marketing. This capability makes the SSD an important option for the city to consider.

Market Incentives

Most of the important funding mechanisms that the city of Philadelphia uses at present involve public-sector incentives for private-sector development. These mechanisms should be carefully evaluated in order to ensure their effectiveness and efficiency.

Ten-Year Property-Tax Abatement

One of the best known of Philadelphia’s economic development incentives is the ten-year property tax abatement program, which holds a property’s tax assessment at its predevelopment level for ten years. The program has attracted national attention and is widely credited with stimulating the recent residential building boom in Center City and adjacent neighborhoods. Between 1997 and mid-2005, over one thousand abatements were approved for new residential construction alone. In this period, the city committed a total of $121 million in property taxes as foregone for a ten-year period on residential projects. This leveraged up to $458.5 million in new market value for the buildings constructed on abatement sites. After the ten-year period expires, the city will capture the full property tax value of these developments.

While the program has been successful in generating new residential construction, critics point to the inequities it can create (such as new residents benefiting from an abatement unavailable to existing residents, who may face increased property-tax assessments) and question its ongoing application in strong markets such as the central Delaware. Also, freezing the property tax for ten years limits the future tax revenues that may be captured within a TIF district, thereby restricting the potential for public investment in value-enhancing infrastructure while placing increased burdens on already strained streets, sewers, parks and open spaces.

Cira Centre

Keystone Opportunity Zones

All land lying north of PECO’s Delaware station and extending to Allegheny Avenue is within a Keystone Opportunity Zone (KOZ), which greatly reduces or eliminates taxes for owners to encourage commercial and business investment. Such comprehensive tax breaks provide a strong incentive for development, but they minimize revenue to pay back bond debt. There are two KOZs within the hypothetical TIF district analysis conducted by PIDC: the incinerator site and the proposed World Trade Center site north of Callowhill Street. If a TIF was implemented there, these sites would not generate property-tax revenue until the KOZ designation expires in 2011.

Tax increment financing, dedicated taxes, grants, tax abatements, special services districts and Keystone Opportunity Zones could each serve as useful tools for development along the central Delaware. Together they help to raise property values, thus improving the development landscape while strengthening the public realm for residents and visitors alike. Some of the strategies for financing the vision presented here could stimulate quality development along the riverfront and provide early funding for infrastructure improvements. Many of these tools could be used together, though others are not compatible. The city must determine how best to balance funding mechanisms that encourage private development with public access and open space along the riverfront. Exploring the tensions and tradeoffs and learning more about how various financing methods would affect private development are important aspects of future work.

Looking Ahead

Determining the right financing strategies will be essential for implementing the recommendations in the civic vision. Fortunately, some research suggests that federal funding for urban-redevelopment projects could increase in future decades. The Brookings Institution argues that the funding of transformative urban-infrastructure projects—large, catalytic projects that enhance the physical landscape and stimulate economic growth—will be required to keep our cities at the forefront of sustainable urban growth. Some federal initiatives may indicate that this funding shift is already taking place. Bills are in various stages of approval to create an affordable housing trust, establish new energy-efficiency standards and allocate hundreds of millions of dollars for streetcar and commuter-rail service. By having a clear vision of desired improvements, Philadelphia would be well positioned should funding policies change at the federal level in the coming decades. Improvements on this scale could be key factors in making Philadelphia competitive as a place to live and work, as well as in allowing the city to capture future growth in the knowledge economy.

Goal 2: Create a Strategy for Comprehensive Implementation, Management and Oversight

Build on existing governance along the riverfront and establish a set of required functions for agencies invested in the future of the riverfront.

Management and oversight of development, design and public investment along the central Delaware will be necessary to realize the civic vision. Currently, a multiplicity of city, state and multistate agencies have oversight of portions of the central Delaware. The coordination of strategies and policies is critical to ensuring that the civic vision and its underlying frameworks are realized.

Management and Oversight Options

The matrix provided below (“Organizations and Departments with Oversight along the Central Delaware River”) shows many of the local organizations that have oversight along the central Delaware. It is evident that realizing the civic vision will require the work of a wide range of public and private organizations. Thus, improving coordination between these efforts should be a focus of future city administrations.

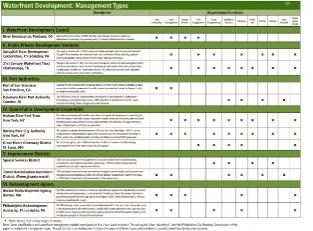

Other cities throughout the nation use various types of regulatory and implementing entities to support riverfront revitalization. The matrix provided above (“Waterfront Development Management Types”) identifies a selection of organizations that represent successful public-private collaborations and self-sufficient entities and describes their organizational functions. This analysis demonstrates the wide range of coordinated functions and services required to engender progressive riverfront development. Whatever form future implementation may take, these are some essential ingredients for success:

Sufficient funding: The most successful waterfront implementation consortiums have lobbied for secured funding from the public sector, such as capital budgets (Portland, OR) or taxes (Chattanooga, TN). Additionally, rather than relying solely on public funds, many implementation bodies have established sources of revenue to supplement governmental funding. Creative funding examples include ground leases, corporate sponsorship and the linking of parks to revenue-generating assets such as parking garages, rental venues and concessions. According to a Regional Plan Association report, New York City Parks and Recreation estimates that the total revenue generated for the agency by all its park concession operations was $61.5 million in 2002.

Shared purpose or vision: Effective implementation strategies must have clearly defined goals that outline the philosophy, as well as action-oriented objectives achieve goals. Working toward the goals will help maintain the momentum of the project.

Leadership and ongoing political support: The scale and the scope of the proposed Civic Vision for the Central Delaware will require patience, persistence and flexibility. Thus, continued leadership is essential. This leadership must include engaging in ongoing, open and transparent communication and forging strong partnerships between community stakeholders and political leaders. Communication and partnerships will ensure that project objectives are implemented— even after a political term ends. Additionally, the existence of an advisory body consisting of elected officials and members of the public will demonstrate a commitment by the community, city and state to the initiative. Some specific functions that leaders will need to address along the central Delaware include:

Planning and design of Delaware Boulevard, a street grid, parks, trails and open spaces;

Land acquisition and conservation;

Construction of public spaces, trails and parks;

Review of development plans to check for compliance with the civic vision;

Maintenance of public spaces;

Raising, receiving and spending of public and private funds for public infrastructure investment;

Collaboration between city and state (both Pennsylvania and New Jersey) agencies working along the central Delaware; and

An open, transparent governance structure.

Looking Ahead

Currently, multiple city, state and bi-state agencies and authorities manage portions of the public realm along the central Delaware. In order to achieve the goals of the civic vision, it is clear that a coordinated and collaborative effort to implement, manage and oversee public infrastructure is required. Further research is necessary before specific proposals for a management strategy are offered. Most of the management efforts studied during this process are single management entities, but that does not mean that existing groups cannot work together to fulfill complementary functions. Philadelphia currently has three riverfront management models to study—the Schuylkill River Development Corporation, the Delaware River City Corporation (along the north Delaware) and the Penn’s Landing Corporation (along the central Delaware).

More detailed recommendations for implementation of the civic vision will be presented in early 2008.

Spotlight: Penn's Landing Corp.

Penn’s Landing Corporation (PLC), the nonprofit, quasi-governmental agency charged with managing a large section of the central Delaware, is the primary public landholder in this area. Despite having an effective professional staff, the history of its politically controlled board is clouded in controversy, and it operates without public input or transparency. This has created public mistrust of the organization and is an issue that must be reconciled should PLC be considered as a possible organization for managing the implementation of the civic vision. PLC has some important assets, most notably its land holdings, which offer the opportunity for public access along 2.2 miles of the central Delaware, along with its ability to raise funds, develop real estate, implement public-improvement projects and provide services like trash removal and landscaping. However, any discussion about the future of PLC and its role in the central Delaware should stress the need for improved governance, transparency and public accountability.

Goal 3: Modernize Public Policy

Forward-thinking regulation and policy can catalyze quality development and promote sound urban-design practices.

Significant policy changes will be needed to ensure quality development and promote design excellence. Incentive programs can be established before policy is written in order to encourage sound development practices from existing landowners and to set the standards for future development of the riverfront.

Public Policy Options

As stated in Chapter Seven, the city cannot rely on the market alone to bring excellent urban development to the riverfront. A sound framework is necessary to ensure the development of high-quality, mixed-use neighborhoods along the central Delaware. The best way to achieve this framework is through public-policy initiatives, specifically zoning changes, as these changes will guide the market toward a better product.

While a zoning classification currently exists for riverfront property— the Waterfront Redevelopment District (WRD)—it is optional, and it offers few prescriptions for use or design. This makes it ineffective even when practiced. Therefore, a more prescriptive set of regulations will be necessary in order for the city to realize the vision presented in this plan for the central Delaware riverfront. See Chapter Seven for a more detailed explanation of zoning recommendations that will augment existing standards used by the North Delaware Greenway and the Schuylkill River Development Corporation.

Looking Ahead

Before the new riverfront zoning is officially instituted, incentives could help encourage sound development practices. Possible incentives for public improvements

include the following:

Matching grants from local or state government,

Various tax breaks, and

Density bonuses for provisions in mixed-income housing, ecologically sensitive design, adaptive reuse and concealed parking structures.

Policy could also be established to regulate the use and form of public space. The needed changes would include the following:

An update of the development permitting process that uses the new zoning overlay to expedite approvals, make the public-input process more effective and ensure that all proposals are considered from a citywide perspective.

An exploration of options for local government land acquisition or the establishment of a land trust (a non-profit organization formed to hold conservation easements and to compile land for preservation). This will be necessary to preserve ecologically sensitive areas along the riverfront and to protect narrow piers from development. Trusts can sell the land to government for public use.

Spotlight: Hudson River Park Trust

Hudson River Park Trust is a public benefit corporation that represents a partnership between New York state and New York City. The Hudson River Park Trust is charged with the design, construction and operation of the five-mile Hudson River Park and greenway. The land is state owned, a remnant of the failed WestWay project, and includes land-use restrictions governing piers and protecting against overdevelopment. The city and state gave the first $200 million in capital commitments, but now the trust is financially self-sufficient due to its revenue-generating capability—it generates about $18 million in operating income per year—and agreements with private corporations. The trust has a fifty-member advisory council of elected officials and representatives from the business, environmental and civic communities. This council plays an integral role in the park-planning process. Recent highlights for the trust include a $70 million grant from Lower Manhattan Development Corporation for park development and the opening of Pier 40 sports fields, which were built with significant support from Nike and the U.S. Soccer Foundation.

Goal 4: Continue the Dialogue

The Central Delaware Advisory Group has called for sustained public input—a hallmark of this planning process—to continue through the implementation stage.

The centerpiece of the planning process for A Civic Vision for the Central Delaware has been sustained civic engagement. New forms of collaboration have helped develop a vision based on shared civic values. The success of this process sends the message that Philadelphians are eager to realize the future of their riverfront according to the planning principles they created. It is essential for citizen involvement to continue, as it ensures that the public good will remain at the forefront of implementation efforts.

Community Engagement Options

At the final Central Delaware Advisory Group meeting in September 2007, group members voted to continue their active involvement in riverfront development efforts and to support the open and transparent nature of the planning process. Voices from the development community also requested ongoing communication regarding the implementation of this civic vision. Continued community participation must allow design professionals, landowners, community residents, business owners, developers and public officials to participate on equal footing. The following are opportunities for ongoing civic engagement:

Involve citizens in the design of public spaces through workshop-type activities or greening efforts that allow them to play a role in the formation of public spaces.

Public feedback has demonstrated that giving community members a stake in the design process has a significant impact on the use and maintenance of such public spaces. This public participation in maintenance could be encouraged through partnerships between city agencies such as the Fairmount Park Commission, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society and community groups. Together, the city and these groups could create “Friends” organizations that would take part in maintaining public spaces along the riverfront.

Create an ongoing feedback process, with regularly scheduled public forums as well as larger events addressing specific development proposals. Sessions should continue to be open and transparent and involve citizens across neighborhood association boundaries to strengthen neighborhood connections.

Establish managing citizen committees or task forces comprised of different community members and riverfront stakeholders that act to guide the civic vision, advocate for its implementation and work with public officials and developers on next steps. Oversight committees would be a way to empower new community leaders, whom the Philadelphia Inquirer refers to as “unencumbered by the politics that can balkanize and paralyze neighborhood life.” Task forces could be organized around the seven citizen planning principles or could focus on specific subjects such as historic preservation, quality of life and development.

Schedule a series of meetings at which the values and principles of the civic vision are revisited to ensure that they are guiding the implementation of the plan. As citizens and others view the existing conditions of the central Delaware and learn lessons during the implementation process, they may suggest that new values be added or that new ways of addressing values be investigated.

Looking Ahead

This planning process has set a new standard for public participation in Philadelphia. The emphasis on citizen participation has afforded Philadelphians a forum to voice their concerns and to develop values and principles fundamental to the creation of the civic vision. Implementing the civic vision will require an ongoing commitment to civic engagement on the part of the city. Interactive and participatory planning is crucial to maintaining a vital and sustainable city in the twenty-first century. Thus, it is imperative that future city-planning processes include active and deliberative civic engagement—an ongoing marriage of citizens’ values and professional expertise that will ensure that policy makers and implementers make informed choices when conducting the people’s business.

More detailed recommendations for implementation of A Civic Vision for the Central Delaware will be presented in early 2008.