Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox

A Civic Vision For the Central Delaware: Land Development

For nearly four decades, public sector attempts to develop the central Delaware have focused largely on Penn’s Landing as the centerpiece for a revitalized riverfront. And while economic and political cycles (along with the physical and psychological divide of I-95) have deterred the development of Penn’s Landing, market forces, aided by an antiquated zoning code, have begun to profoundly shape the physical form of the central Delaware. The results are best represented by the profusion of large-scale, single-use projects, such as the big-box retail district in South Philadelphia and a gated condominium community north of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Studies

indicate that the development of a riverfront into a local and regional destination is more likely to achieve sustained success when plans accommodate a wide range of compatible uses. Development controls and land-use policies are essential to promote high-quality, mixed-use urban development.

Land Development (pdf)

Purpose

Like movement systems and open space, and development has overarching implications for the riverfront. The civic vision’s purpose, then, is similar here: to redevelop the area adjacent to the river’s edge in ways that are urban, human-scaled, ecologically sound and transit-oriented, ways that create economic opportunities for the private sector while affording public access to the river and its open space network.

General Findings

The project team found strong evidence that economic, social and environmental returns increase with sound urban design and planning. Quality urban design guidelines allow for the creation of site plans and buildings that reflect the civic values of public access and urban connectivity, employing a variety of regulatory tools (both physical and economic) to achieve a reasonable balance of buildings, public spaces and land uses. Quality urban design has the potential to increase sales and leasing revenues, increase public safety and contribute to the revitalization of adjacent and nearby areas. It can also generally reduce living costs through the inclusion of mass transit and mixed-income housing. Research indicates that an increase of up to 20 percent in rental and capitalized values can be created by high-quality urban design and that one dollar of public investment in infrastructure and other improvements to the public realm can leverage up to twelve dollars in private investment.

Land-Development Goals

Together, street networks and openspace systems create a framework within which land development may occur. However, effective land-use policies are crucial to the achievement of a dense, pedestrian-scale urban environment. The following goals can serve to guide Philadelphia as it reevaluates its current land-use policies along the central Delaware:

1. Capitalize on Economic Potential. Based on current economic trends and forecasts, the city has the opportunity to balance investment in public infrastructure with quality development.

2. Implement Development Guidelines for the Riverfront. The city has the opportunity to provide responsible riverfront land-use guidelines for property owners and developers so that the development of the central Delaware riverfront can be realized in accordance with the civic values embodied in A Civic Vision for the Central Delaware.

3. Explore Innovative Approaches to Parking. Develop a parking policy that lessens parking’s visual and operational impact on the streetscape and the pedestrian environment.

Goal 1: Capitalize on Economic Potential

Based on current economic trends and forecasts, the city has the opportunity to balance investment in public infrastructure with quality development.

The central Delaware riverfront has the potential to be a vibrant, pedestrian-friendly series of mixed-use neighborhoods and development sectors that are also economically, socially and environmentally sound. Its location along one of the nation’s great harbor rivers and its proximity to Center City afford the central Delaware substantial possibilities for residential, industrial and commercial growth. The civic vision can be realized if land development is based upon a long-term vision one grounded in an understanding of the city’s economic potential.

Discussion

Philadelphia’s economic health was seriously challenged by significant population and employment declines in the late twentieth century. While the city continues to struggle with poverty, job growth and the retaining college-educated young people, some recent economic trends and forecasts provide reason for optimism. For instance, recent population increases in Center City, along with an anticipated citywide growth in employment over the next twenty years, are likely to improve Philadelphia’s overall marketability and create new opportunities for residential, office, industrial and retail space. Recent trends and forecasts suggest the following:

Patterns of population loss vary significantly by neighborhood. While neighborhoods such as West and North Philadelphia have lost population, redevelopment initiatives coupled with the residential property-tax abatement program have produced 11,586 new housing units in Center City since 1997, with an average increase of 1,390 units per year since 2000. In fact, 1,932 new housing units were constructed in 2006, and another 1,189 are under construction. A recent study named Center City one of five “fully developed downtowns” in the country, all of which are characterized by a large population, a high percentage of wealthy and college-educated residents and steady household growth since 1970. In addition, according to population forecasts prepared by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC), the rate of population loss citywide is expected to slow by 2030, with continued growth in Center City, a stable population in South Philadelphia and slight gains in lower North Philadelphia.

Philadelphia is projected to add approximately 52,000 new jobs citywide between 2010 and 2030, according to Woods & Poole, Inc., a demographic forecasting service based in Washington, D.C. (the only private source of long-term employment forecasts).

An economic analysis completed by Economics Research Associates (ERA) examined four prototypical sites along the central Delaware River. These sites were Pier 70 in South Philadelphia, Festival Pier at the foot of Spring Garden Street, Penn’s Landing and the Port Richmond rail yards. They stated that four thousand new households could be added on these sites by 2030. ERA then conducted a preliminary retail-demand model using these four thousand new households and found that, assuming an average annual income of $50,000, these new households would generate $200 million in gross annual income, which could be expected to create roughly $43.4 million in retail-spending potentials—a potential that may be dispersed across the city.

ERA’s analysis goes on to estimate that the total tax revenues for the four study sites could approach $177 million on an annual basis. At buildout, these sites are estimated to have a combined 2,500 new housing units and 14,000 employees. It is important to note that these four sites serve as prototypes; the economic benefits associated with them could be applied more broadly to other redevelopment projects across the project area. See Chapter Eight for a more detailed discussion.

Moreover, the addition of 52,000 new jobs citywide over the next twenty-five years could result in a series of positive consequences. If these new jobs materialize, they are expected to produce demand for roughly sixteen million square feet of commercial space citywide. Some employment growth can be accommodated in existing vacant space. But with the extensive amount of vacant and underutilized land available along the city’s riverfront, it is reasonable to consider that a portion of these needs could be accommodated on the central Delaware. The addition of that many new jobs would also translate into consumer spending, which in turn would increase demand for retail space. Despite the short-term public sector costs of subsidies, riverfront redevelopment will provide fiscal returns to the city of Philadelphia. As stated previously, one dollar in public investment in infrastructure (streets, boulevards, parks and trails) can yield up to twelve dollars in private investment. Achieving these outcomes will require proactive public policies, including clear and cohesive economic-development strategies, specific business retention and recruitment efforts and reductions in the business, wage and professional licensing taxes.

Early Action

The city should commit to building and maintaining high-quality public spaces. The first phase of this goal is the identification of catalytic projects. These projects can include infrastructure improvements (roadways, transit-station upgrades, parking structures, etc.) and civic amenities (public open spaces, event programming, community facilities, etc.). It is important that the city takes the initiative and invests in the public realm, as these investments will help induce and sustain growth. In doing this, the city will ensure that the riverfront is developed in a way that balances public and private goals and thatdemonstrates an ongoing commitment to the revitalization of the riverfront.

Recommendations

Comprehensive and equitable development policies require the judicious use of public dollars. Proactive investment initiatives are essential to inducing and sustaining growth and creating demand. The civic vision recommends that the city do the following:

Explore tax increment financing (TIF) in a district-wide manner. Widely used across the United States, TIF is a form of financing incentive in which future tax revenues generated by new development (established during a baseline year) are guaranteed on bonds issued to fund up-front capital improvements, such as the upgrading of infrastructure and the inclusion of open space. A TIF’s ultimate goal is to support future development. See Chapter Eight for additional details on the benefits of TIF districts.

Goal 2: Implement Development Guidelines for the Riverfront

The city has the opportunity to provide responsible riverfront land use guidelines for property owners and developers so that the development if the central Delaware riverfront can be realized in accordance with the civic values embodied in A Civic Vision for the Central Delaware.

The current Philadelphia Zoning Code is outdated and provides little to guide the significant development pressures along the central Delaware. Nearly all new development in the project area requires a zoning variance in order to be realized, making most projects subject to review and negotiation by civic associations, the Zoning Board of Adjustment and City Council on a parcel-by-parcel basis, without regard to comprehensive planning or sound systems thinking. The result is a fragmented collection of uses along the riverfront, from big-box stores to gated communities built, without a cohesive public- space framework, independent traffic-impact studies or mitigation recommendations, or anunderstanding of the environmental impact of the development on the river and the city’s fraying infrastructure. Unaided by clear rules or a plan for appropriate riverfront development, most of the currently proposed residential and commercial development in the project area follows the current trend of suburban-style, automobile-dependent designs that separate the city from the river. Philadelphia must establish sound and responsible riverfront zoning that balances quality development with public-interest concerns about access and open space.

Discussion

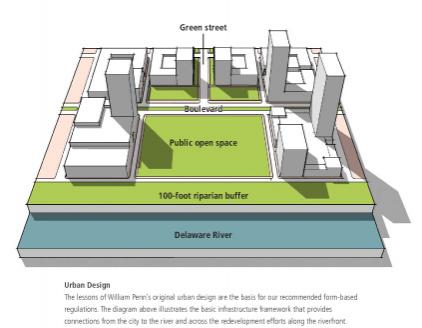

Studies from around the world indicate that economic, social and environmental returns increase when urban design is of high quality. Center City Philadelphia is a local example; in recent years it has grown to become the third largest downtown in the nation, currently absorbing about two thousand new housing units per year, with 41 percent of new occupants moving from outside the city. Thanks to its pedestrian-scaled street network, it also has the largest population that walks to work of any downtown in the country. A Civic Vision for the Central Delaware envisions the central Delaware as an extension of the human-scaled street grid of Penn’s original plan for the city. Implementing sound zoning will ensure that buildings and development fill in the grid in a manner that protects the public’s right to have access to streets, sidewalks, parks and the river. This civic vision’s focus on serving neighborhoods, city residents and visitors by developing beautiful places for all citizens will make the central Delaware a world-class riverfront that everyone can enjoy.

To achieve this level of quality urban design, a new policy framework is necessary. The power of policy is already clear in Philadelphia, as neighborhoods such as Society Hill, Yorktown and Eastwick were the result of deliberate development and zoning efforts. Indeed, the work of the current Zoning Code Commission underscores the public’s commitment to zoning reform. Some of the most popular waterfront destinations in North America are the product of numerous stages of planning, including Baltimore’s Inner Harbor and Vancouver’s Granville Island. New York’s Battery Park City took decades and careful phasing before high-quality redevelopment occurred. Numerous cities around the country, including Denver, Chicago and Milwaukee, are instituting new zoning codes in order to encourage quality urban development.

Early Actions

Writing and adopting an interim zoning overlay is the first action necessary to ensure that the values and principles embedded in the civic vision are protected. In the short term, the zoning overlay will provide communities with guidelines upon which to evaluate proposals. This civic vision also recommends a long-term zoning ordinance that ensures that civic values are fully realized. The following are suggested elements for new zoning regulations (both interim and long term):

Require access to the river approximately every 500 feet that connects to the existing city grid. Based on the average Philadelphia block size, the proposed street-access grid ensures that buildings would be no wider than 500 feet, with streets and walkways granting public access and river views.

On publicly controlled land, such as Penn’s Landing and Festival Pier, public access shall exist every 250 feet.

Provide for a 100-foot riparian buffer where possible for a riverfront trail, stormwater management and recreational use.

Buildings should be built up to the sidewalk line, with active ground floors along the boulevard and primary streets. Ensure that there are no blank walls on primary streets.

Integrate towers into low-rise building blocks by staggering them so as to ensure views from adjoining buildings. Ensure that tall buildings front open space, when possible, with the open space scaled to serve the density of the surrounding development. It should be noted that this team does not view building heights as a key determining factor in quality development in the short term.

Do not allow parking and building-service requirements to dominate the riverfront. Limit visible surface-parking lots and freestanding- structure parking garages. Create service streets (like Sansom Street) for parking and service entrances to buildings and developments.

Consider increased-height and density incentives to developers making use of progressive parking solutions.

Ensure that sidewalks are pedestrian-friendly by limiting curb cuts and driveways.

Protect and enhance the environment by requiring sustainable building practices such as green roofs, passive solar energy, car sharing and other environmentally friendly planning and building techniques.

Provide incentives for inclusionary zoning that enables mixed-income housing along the waterfront.

Ensure that the riverfront retains a mixture of uses by not allowing single uses to dominate.

Protect the past by ensuring that existing buildings are preserved, adapted and reused. Use the Philadelphia Historic Preservation Ordinance to protect the architectural, cultural and historic heritage of the colonial and industrial periods. Adaptive reuse of historic structures and sites should be pursued to enhance new development.

Facilitate planning and policy-writing efforts with developers, land owners and citizens so that public and private goods are served in walkable, mixed-use riverfront communities. These efforts would include workshops and educational programs on the merits of sound urban design. These planning and policy-writing efforts would replace the current method in which stakeholders review preexisting proposals that are already moving through the zoning system.

Incorporate public art into open-space and building designs.

Recommendations

Zoning initiatives establish a framework for future development. With these tools in place, the city will be able to realize the civic vision of enhanced riverfront access, new public open spaces and quality, mixed-use neighborhoods. In the longer term the city will also need to accomplish these zoning-related aims:

Create a master plan for the central Delaware in conjunction with the work of the Zoning Code Commission. This master plan should address desirable densities along the riverfront (with a minimum Floor Area Ratio of 4 in most areas without existing residential fabric). Drawn from this master plan, a permanent zoning ordinance should determine density and intensity appropriate for districts of differing character on the central Delaware. We recommend that the Zoning Code Commission consider the following potential subdistricts:

North: Allegheny Avenue to Penn Treaty Park

North Central: Penn Treaty Park to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge

Central: Benjamin Franklin Bridge to Washington Avenue

South: Washington Avenue to Oregon Avenue

Port: The existing Port of Philadelphia, south of Snyder Avenue

Adopt the extension of the street grid by adding it to the official city plan. The extension of the street grid across the central Delaware would result in an average block size of 400 feet by 500 feet, which would become the framework for future growth and development. This would ensure that the public has access (both physically and visually) to the river along connected streets every 400 or 500 feet— roughly the equivalent of one Center City block.

Enact housing, tax and land-use policies that effectively manage neighborhood change in the project area.

Coordinate long-term planning with the Philadelphia Regional Port Authority, the Philadelphia Commerce Department and the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation to ensure that future riverfront development corresponds to positive growth of the working port and other job-producing uses.

Encourage job creation and business incubation along the riverfront.

Coordinate development of the riverfront with the growth of the Philadelphia Navy Yard as a commercial and industrial center.

Design all public spaces, buildings, parks, roadways, trails, bridges and infrastructure along the central Delaware riverfront to the highest contemporary design standards. Coordinate design review, implementation, management and oversight to ensure excellence.

Integrate contemporary public art into public works and open spaces.

Goal 3: Explore Innovative Approaches to Parking.

Develop a parking policy that lessens parking’s visual and operational impact on the streetscape and the pedestrian environment.

Large portions of the central Delaware riverfront are dedicated to parking lots, and many proposals for riverfront developments feature “podium” garage structures that block views and access to the river. The auto-dominated nature of the riverfront diminishes its potential for quality, human-scaled urban development and public space. The abundance of both underutilized land and development interest in the project area gives the city a rare opportunity to integrate parking into a well-designed urban context instead of allowing it to define the streetscape and detract from the pedestrian experience. The civic vision proposes policy initiatives that ensure that vehicles do not dominate the riverfront. Though parking is an essential component of any transportation system, a successful riverfront must actively promote a pedestrian-friendly, transit-oriented development pattern that will balance pedestrian and auto-oriented uses.

Discussion

The city is in the midst of a shift in its traditional thinking about parking design and policy. Philadelphians are demanding a higher-quality urban environment in which parking facilities enhance the public realm. It is no longer enough simply to reduce the negative impacts of parking by regulating location and garage size. The city is developing requirements and incentive-based policies focused on improving parking-structure design, as well as incorporating an integrated transportation policy that encourages the use of transit. Elements of such policies could include encouraging PhillyCarShare, an expanding regional car sharing program; identifying locations for remote parking; and using innovative systems such as automated garages. Automated parking systems offer many benefits and are ideal for the urban environment. They feature lower maintenance costs than traditional structured parking and generally need 50 percent less space to handle the same number of vehicles.

Many cities have begun to experiment with innovative parking strategies. Chattanooga, Tennessee, has developed peripheral parking garages and a free shuttle service to its central business district, which intercepts commuters and visitors before they drive into the city center, thus reducing traffic problems. Copenhagen and Seattle have installed real-time, computerized parking systems that are designed to guide drivers to available garages and parking spaces.

Spotlight: PhillyCarShare

PhillyCarShare has grown to more than twenty-five thousand members since its inception in 2002, making it the world’s largest regional car-sharing organization. This flexible system has removed over eight thousand cars from Philadelphia streets, reduced pollution and saved each user an annual average of $4000.

PhillyCarShare’s popularity challenges the city’s zoning requirement of one on-site space per new residential unit constructed. PhillyCarShare is forming partnerships with developers to assert that each PhillyCarShare parking space in an urban residential development reduces the need for up to twenty-five private parking spaces per development. Encouraging more PhillyCarShare pods in the project area (or encouraging developer-subsidized car sharing) will reduce construction costs for developers and provide positive environmental bene.ts for the general public.

Early Action

To be successful, a riverfront requires the right balance of pedestrian, transit and vehicular traffic. To achieve a desirable balance on the central Delaware riverfront, the city should create incentive-based policies that facilitate responsible parking strategies. We recommend that the city develop a coordinated transportation, traffic and parking policy for the region that encourages land and waterborne transit and mandates some combination of car sharing, remote parking and commuting allowances for riverfront employees, as well as other strategies that will lessen the effects of traffic and parking on riverfront land.

Recommendations

Parking should not be allowed to dominate the riverfront landscape in the form of visible surface lots, freestanding-structure parking or exposed parking podiums. Instead, parking should be built on service streets (as it is in Center City Philadelphia), embedded within the mass of a building or placed underground (when this is economically and environmentally feasible).

Implementing the following parking initiatives will help the city realize a pedestrian-friendly riverfront:

Institute new zoning regulations along the riverfront that limit the number of parking spaces per development and that require investment in the establishment or maintenance of transit stops, car share parking, bicycle parking and other car-reduction programs.

Educate lending institutions on the economic benefits associated with developing a project that includes reduced parking and/or well-designed parking.

Establish a policy that offers developers height and density bonuses to developers for projects that embed parking within their buildings, place parking underground, utilize remote or valet parking as appropriate and promote mass transit.

Incorporate designated car share and bicycle parking spots into future development requirements for riverfront property.

Form partnerships with Camden’s Tweeter Center, the Camden River Sharks and the Philadelphia Sports Complex to use their underutilized parking areas on non-event days for remote parking.

Incorporate sustainable-design standards into the design guidelines for surface or on-street parking. These may include the use of pervious surfaces, enhanced landscaping and other creative methods for stormwater capture and processing.

Raise parking-meter rates in locations where spaces are at a premium, and enter into agreements with local developers to share parking revenues. These revenues could be used for providing public amenities or for the ongoing maintenance of public spaces.